Héctor Germán Oesterheld’s and Francisco Solano López’s “Enterradores” (gravediggers)

A curious thing happened when Argentinian scriptwriter Héctor Germán Oesterheld found his own comics publishing house, Editorial Frontera. For a brief period of time, 1957 – 1963, mainstream adolescent comics raised much above the business as usual, pervasive formulaic dreck. Oesterheld proved to me a very simple and often forgotten truth: it’s easy to dismiss a whole category if we base our judgment on the worst examples (usually those are the only ones that the judges know about). It’s easy to debase something when the judge is socially much above the subject of her/his scorn; in these circumstances s/he can only be applauded by her/his peers while all outraged reactions can’t be heard outside of the attacked subculture.

I don’t defend adolescent comics, mind you, I’m just saying that when the best comics writer ever decided do try a hand at this particular genre (if we can call it that) the inevitable happened. Here’s what he had to say in Hora Cero Suplemento semanal (zero hour weekly supplement) # 1 (September 4, 1957):

There are bad comics when they’re badly done only. Denying comics all together, condemning them as a whole, is as irrational as denying cinema all together because there are bad films. Or condemning literature because there are bad books. There are, unfortunately in a huge ratio, lots of bad comics. But these don’t disqualify the good ones. On the contrary, by comparison, they should underline their quality. […]

Oesterheld is a German family name and Héctor inherited a German tradition which, according to Christian Gasser (in the Lisbon comics convention catalog, 2003) dates from the enlightenment:

This didactic interpretation of literature is a product of the 18th century. At that time, the qualities of literature and art were used to educate and morally elevate the common people. Meanwhile, these efforts became obsolete in literature, but not in the restricted domain of children’s literature where people continue to ask: “Very well, what can a child learn from this book?” The pedagogic function continues to be overrated.

Oesterheld viewed the, then, popular medium of comics as an opportunity to reach hundreds of thousands of children and adolescents. At a certain point he felt the need to put the following warning on the cover of Hora Cero Suplemento Semanal: “Historietas para mayores de 14 años” (comics for those who are older than 14). The anti-comics crusade was still on and he didn’t want any trouble. Anyway, he wanted to both educate and entertain. What he meant by “educate” wasn’t exactly what may be on our minds today though…

He aimed at four goals: (1) to be accurate with his data (pedagogic texts about warfare punctuated his comics; he wrote stories in a lot of genres – Western, Science-Fiction, Historical, Noir –, but War – WW2, to be exact – remained the bulk of his magazines’ content); (2) he didn’t want to edulcorate reality or bowdlerize his stories; (3) he wanted to convey moral values of self-sacrifice, unselfishness, team work (he strongly opposed the individual macho hero as he – it’s usually a “he” – is seen by North American mass artists; ditto the glorification of violence… besides, the main character is usually someone socially “invisible” who reacts unexpectedly in a stressful situation); (4) linked to (2): Oesterheld didn’t want to hide what’s darker in the human condition, but, at his best (he produced hundreds of stories, so, lots and lots of them aren’t that good) he was never Manichean.

Four great draftsmen drew Oesterheld’s stories at Editorial Frontera before working (immigrating even) exclusively for the UK. After these artists disbanded the graphic quality of Frontera’s stories dwindled dramatically. Not even a young José Muñoz could equal them:

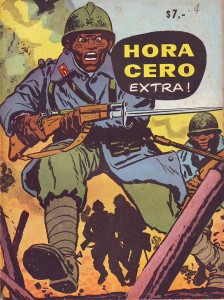

Hugo Pratt:

Hora Cero Extra! # 4 October, 1958.

Hugo Pratt did very rare unprejudiced portraits of black people in the 50s. In this Hora Cero Extra! cover he illustrated a story by Oesterheld about Senegalese soldiers fighting for France during WW2.

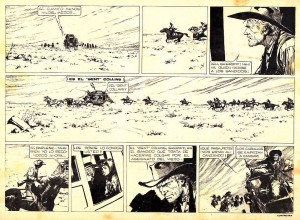

Arturo del Castillo:

Hora Cero Suplemento Semanal # 58, October 8, 1958.

An impressive Western scene from “Randall.” Castillo would do for the UK the best The Man in the Iron Mask comics illustrations ever.

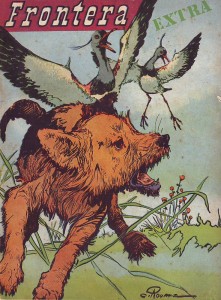

Carlos Roume:

Frontera Extra # 7, May 1959.

Roume was a great animal artist. In this Frontera Extra cover he drew Pichi, the Pampa dog. A story scripted by Héctor’s brother, Jorge.

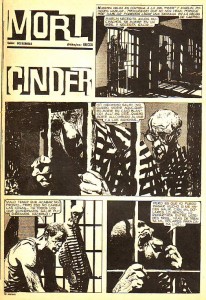

Alberto Breccia:

Misterix # 749, March 22, 1963.

Alberto Breccia and Héctor Germán Oesterheld’s Mort Cinder (a series that, in my view, isn’t as good as Ernie Pike) remains one of the most famous of Oesterheld’s creations (along with Argentinian cultural icon: El Eternauta – the eternaut). This doesn’t surprise me because of comics fans’ bent for fantasy. Even so the story to which the above page belongs, “En la penitenciaria: Marlin” (in the penitentiary: Marlin), is one of the series’ best ones.

I immersed myself in Oesterheld’s oeuvre for the last year. Reading hundreds of his stories I can safely say that he could have been one of those world famous South American writers like Jorge Luis Borges. Borges and Oesterheld knew each other and used to take walks together. Oesterheld was an inventive plotter and a purveyor of ideas and great phrases. Even when the story is no good at all (as I said, he produced too much) a phrase sparkles suddenly making the reading worthwhile.

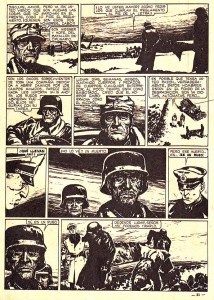

I stumbled upon lots of Oesterheld’s great stories, but I had to choose one for this Stumbling. I chose “Enterradores.” In it a German major freshly arrived from Berlin to the Stalingrad front is shocked when he discovers that two German soldiers (Wesser and Hofe) of the disciplinary battalion (whose mission is to bury corpses) are burying Russians and Germans together:

Hora Cero Extra! # 1, April 1958.

The drawings are by Francisco Solano López. To be honest I don’t like Solano’s drawings as much as I like the work of those four artists above. I find his understanding of the human figure a bit strange and his lines a bit heavy and formless sometimes. Even so it seems to me that he captured the facial expressions of the veterans well in contrast with the major’s. The overall darkness of the atmosphere is more than adequate to convey the theme of the story.

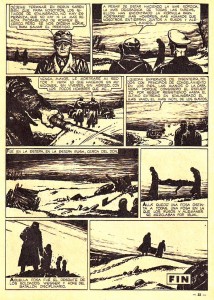

The captain explains to the major how desperate the situation is (he wants to excuse the two men’s lack of discipline). Here’s what Oeserheld wrote in the last two strips: “It was in the Steppe, near the Don. / There stayed a shared grave different from all the others. A grave in which Russians and Germans mixed. / That grave was the revenge of soldiers Wesser and Hofe of the disciplinarian battalion.” Equally impressive are the eerie shadows walking into oblivion at the end…

Can you imagine such a story in a children’s comic today? It wasn’t even suitable for a children’s comic back in the 50s. And yet, Argentinian kids bought Hora Cero and Frontera in their various incarnations. Judging from Oesterheld’s example, maybe I’m not against children’s comics… maybe I’m against children’s comics that insult their readers’ intelligence, that’s all…