I recently deserted the mainstream of comics and this month, the first product of my emancipation, an improvised comic with a flexidisc attached called Post York done in collaboration with my son Crosby is being released by artist Tom Kaczynski’s alternative imprint, Uncivilized Books. Although there may be little financial compensation forthcoming, I couldn’t be happier. Because I am free now, free of digital fonts and color, free of the dictates of corporate editors, marketers and number-crunchers, all fearful of offending middling demographics. Some of my contemporaries have likewise abandoned corporate comics; perhaps because of the increased visibility of inequities like the Kirby family’s loss in court to Marvel/Disney’s crush of lawyers (largely due to testimony by an invested individual with a famously faulty memory), as well as anti-creative projects like DC’s Before Watchmen.

While the mainstream seems locked into a suicidal transition into collector-unfriendly digital formats; the print alternatives are taking advantage of the fact that comics and graphic novels are a fast-growing portion of the dwindling book market. As the mainstream devalues individual accomplishment in favor of collective product that is actually primarily intended for adaptation to other entertainment forms, the alternative gains ground in sales and critical attention. In fact, by their near-universal acceptance, the leading luminaries of the alternative like Art Spiegelman and Chris Ware now risk becoming a new establishment, which will eventually need to be overthrown in order for the next alternative to be formed.

___________________________________________________

But that revolution is still a ways off. And, some alternatives have not yet completely divorced from the look of the mainstream. In 1999 I drew one of writer Greg Rucka’s earliest comics scripts, “Guts” for Vertigo’s late horror title Flinch. Rucka writes stories that might as easily be realized in the mediums of film or television, but he became an acclaimed comics writer for DC and Marvel. However, he has in recent times taken a stand against their abuses and his newest work Stumptown is published by a small alt-comics firm Oni Press. While it has a digital surface similar to that of the mainstream, it is bereft of the focus-group mentality of the corporate comics product purveyors. The story has a downscale title, it features a female lead character of funky agency and wry humor and Rucka’s collaborator, the artist Matthew Southworth is not slick, but still gives the work the seemingly effortless video realism that it needs to be believable, and more: Southworth is capable of hard-to-accomplish nuance. For instance, he manages to make it quite clear that the lead character’s brother has Down’s Syndrome without resorting to caricature.

Southworth’s layouts are exceedingly clear and his inking is contemporaneous but organic, and although I have an aversion to digital color, here it works and is particularly effective in the nocturnal concluding sequence. As with many recent book trade repackagings of periodical comics, the $29.99 hardcover of the first four issues can seem an overly upscale presentation of what is essentially pulp crime fiction, but the book gives the reader a complete story that is as absorbing as an HBO miniseries and also has the appeal of pure comics storytelling.

___________________________________________________

Koyama Press puts out elegantly designed books that are more distantly removed from the look of mainstream comics. Koyama’s recent output shows quite an extreme range of publications, their only unifying factor their beautiful production values. I have been taken aback by the prices of alternative comics, but as Marguerite Van Cook points out, Koyama’s efforts and those of other alt/lit comic books reflect a sensibility that opposes the mainstream model. Mainstream pricing is not cheap either and is supported by advertising. Their books are apparently geared primarily as concept generators, to which end they privilege character/property and devalue artists. The comics can be published at a loss because they are underwritten by the corporation as pools for movie ideas. By contrast, a Koyama comic, for instance, is an individual accomplishment that is facilitated by the publisher; the final product is all about the value of the artist, all about being the most clear expression of the person who made the book.

Eat More Bikes by Nathan Bulmer is a collection of one or two-page jokes, literally a “funny-book”. The book is nicely printed and although digitally toned, the art is scratchy and clearly drawn by hand—it reminds me a little of early Peter Bagge. I found the pages to be sometimes mystifying, at times disturbing, some were hilarious even, but I’m thinking that I may not be the ideal audience for this thing.

The photograph of the author on the back page depicts him with the beard that he grew while drawing the book, thus he takes ownership of his product and self-identifies as a member of a tribe, a generation perhaps, of shared sensibility—-who more than I may greatly appreciate his humor and want to support his efforts by paying 10 dollars for the comic he made.

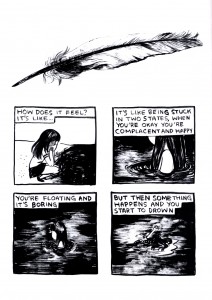

I can relate better to another, identically priced Koyama offering, Sunday in the Park With Boys by Jane Mai. The striking cover depicts a black and white figure of a young girl decked out as Sailor Moon with a monstrous bug crawling over her head, on a blue ground. This image and the quiet desperation of the contents counter the sweetness of the title. The protagonist is a teenaged girl, however she is not well socialized with her peers but rather a terribly isolated individual who often wears an eyepatch (whether by necessity or for affect is unclear) and works a job in a rarely used wing of a library. The pain of her loneliness, however self imposed, is palpable.

The panels are stark and simple but heavily inked with a drybrush technique and each short sequence in the story begins with a more realistically rendered drawing of an object: a key, a cellphone, a quill, a hand mirror, a pair of panties; these and the bug motif that creeps through the comic anchor the narrative to the “real world”. The first time I read the comic, I found it depressing; on rereading I began to see how the character comes to grips with what is going on in her mind to transcend it and that the story expresses a sort of universality of lonesome youth.

Two other Koyama books, entitled Wax Cross and Baba Yaga and the Wolf, are the work of a collaborative duo, Pat Shewchuk and Marek Colek, that call themselves Tin Can Forest. These full color magazines are astounding efforts and disorienting reads. They are “comics” only in a broad and strangely fluid sense, because the panels run together, due to faint or nonexistent boundaries between them and across the spread of the pages. The panels themselves are done in techniques that I am unable to identify; they look to be full paintings, perhaps partially done with stencils.

Beautiful and confusing, the levels of thought, skill and effort involved in these publications justifies their cost of $20.00 each and they surely push towards the realm of finely printed art.

___________________________________________________

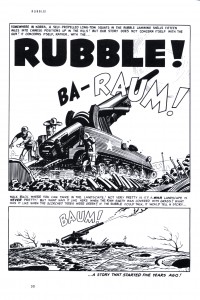

Fantagraphics Press is the standard-bearer and highest exemplar of alternative comics in America. Not only did they bring the greatest of the current generations of literary cartoonists to prominence in the first place, plus they continue to fearlessly publish groundbreaking new talents as they emerge, but they also have made it their business to ensure that the greatest works in the history of the medium are put back in print in handsome, durable volumes. In fact, to continue the tone of blatant self-promotion that I started this piece with, in a few months they will release a new edition of 7 Miles a Second, another work of mine (with Marguerite and the late David Wojnarowicz) first seen at DC/Vertigo. But I digress. A project that Fantagraphics have undertaken recently is a set of hardcover books reprinting the stories of select E.C. Comics artists, in black and white. I imagine the series will be quite satisfying for anyone who wants to see the linework of various artists represented such as Jack Davis, Wallace Wood and Al Williamson unadorned by Marie Severin’s very well done but sometimes obscuring colors. I have the Harvey Kurtzman volume, Corpse on the Imjin and as usual the design and printing of the book are beyond reproach. Now, here’s a little criticism about the Kurtzman book. Perhaps I should have read the copy on the solicitation more carefully, because when the book came it was close to comic book size…I had expected something a bit oversized, to be better able to appreciate the drawings.

And while I greatly admire the beautifully constructed and moving solo stories by Kurtzman from his two war titles Two-Fisted Tales and Frontline Combat that are included and anyone who knows me, knows I absolutely LOVE the sophisticated stories he did with Alex Toth, and that I admire as well the stories finished by other artists that Kurtzman wrote and laid out that are included, I had somehow assumed this book would first and foremost be a collection of solo stories! He did other stories on his own at that company that are NOT included: the first thing he did for E.C., the V.D. story “Lucky Fights it Through” that can only be found in an old issue of John Benson’s fanzine Squa Tront(#7); and he did solo tales for other titles in E.C.s horror and science fiction lines, some that have seriously detailed artwork, all show his singular and distinctive style. In my opinion, including them would have made for a more comprehensive and essential collection of Kurtzman’s E.C. comics work than including works finished by others. But all that being as it may, still at $28.99 the book is a goodly chunk of high-quality material.

The publishers are at their best, though, when they display the courage needed to print books like Josh Simmons’ horrific The Furry Trap. I realize I am a little belated in reviewing this, but for some unknown reason, I only just got to it—and then, I was stricken by its contents! Let’s not even go near how they got away with printing the story about a certain caped crusader; suffice to say that as degraded as it is, it is the most accurate depiction I have seen of what I know in my heart of hearts the nature of America’s favorite fascist vigilante hero to be in essence. But to get there, first one has to endure Simmons’ initial foray: an elf, wizard and dragon story of such onerous and persistent perversity that it is nearly enough to inspire one to burn the book with the remainder unread. It is as if the penis-hacking doctors smashing their patient’s faces with huge mallets in Chester Brown’s Ed the Happy Clown were taken as the starting point to a brave new world of semi-humorous but unfettered graphic ultraviolence.

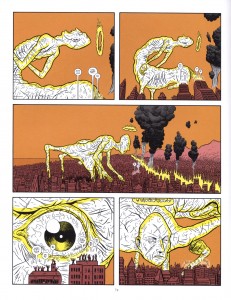

My personal favorite of the stories is “Jesus Christ,” reprinted from where I somehow missed its original appearance in MOME. Loving as I do extravagant crypto-religious statements, this apocalyptic vision certainly suits my preferred image of the fate that awaits the throngs of pious middle American fake-Christians when and if the Lord returns. It is funny that the Publisher’s Weekly review of the book dismissed this story as “flimsier than (the) others”, when to me this is the most obvious masterpiece of the book, a short but densely drawn epic of utterly fearsome aspect and attenuated gesture that the artist apparently labored on over the course of two years!

There is plenty more; the $24.99 book is packed cover to cover with shudders that cannot be anticipated, that grow worse as they progressively become less clearly defined. The last narrative is the most frightening because it is a straightforwardly articulated bit of cinematography on paper that, as with the most effective of suspenseful creations, gains in impact from what is never shown, the reader’s mind having already been prepared by the foregoing tales to expect the worst. And so this is where the freedom of the alternative leads, not just to horror but to push further, into the unknown, good and bad and never-before-seen.

________________________________________________________________________