This first ran on Splice Today.

_______

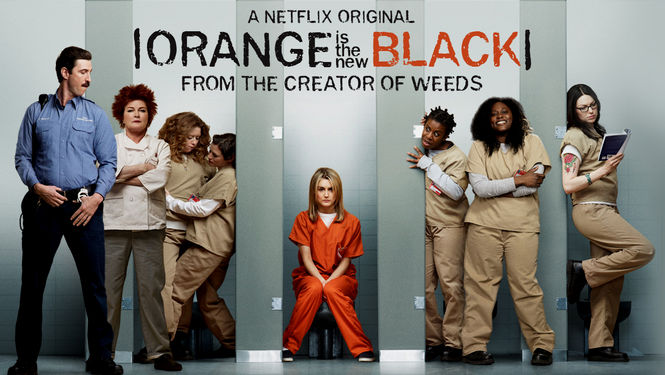

After the first season of Orange Is the New Black, some writers like Yasmin Nair criticized the show for its focus on, and subtle bias towards, white women, especially towards star Piper Chapman (Taylor Schilling). The second season addresses these complaints head on. In episode eight, Piper gets a furlough to visit her dying grandmother, despite the fact that many other prisoners, mostly black, have been refused furloughs to see ill loved ones. Piper becomes the (understandable) target of much resentment, and after getting angrier and angrier, she stands up in the cafeteria, apologizes on behalf of white people everywhere, tells them that even though her grandmother is white, she still loves her, and encourages her tormentors to “shut the fuck up.” After which, Suzanne (Uzo Duba), on behalf of the other inmates and (presumably) the viewing audience, throws cake at this privileged, whiny little ass. End of moral.

But in the book on which the memoir is based, Piper didn’t actually get furlough. She asked to see her grandmother die, but the state said, “no.” Piper in real life certainly was middle-class, and privileged in many ways—not many ex-prisoners go on to write famous memoirs that get turned into hit TV series. But the privilege presented on the show in episode eight, what she’s punished for, wasn’t actually a privilege she had. On the contrary, she was, in this matter, treated just like every other prisoner; with callous, bland disregard and petty authoritarian vindictiveness.

You could say that this doesn’t really matter; the dramatic point is that Piper is middle-class and white and is therefore better off than her cellmates. The incident in the cafeteria demonstrates that; why nitpick about details?

I think it’s worth nitpicking about details, though, because the moral here about Piper’s privilege is a little confused. Specifically, the show seems in many instances so eager to pull Piper down a peg, and to show that she’s privileged, that it can elide the fact that, white as she is, she’s in prison. Moreover, she’s in prison on a decade-old charge of having transported heroin. She committed a pretty low-level crime a while back, and so she’s taken away from her family and robbed of her freedom. She may be privileged in comparison to some of the people in prison with her, but compared to many viewers (and not just white ones) her life, as chronicled in the show, sucks.

This isn’t to say that race is irrelevant. But for the real Piper, racism did not allow her to go see her grandmother: racism prevented her from seeing her grandmother. Racism was used against her, not in the sense that she was discriminated against because she was white, but because the mechanisms and institutions built to police black people ended up policing her.

Racism against black people has been used as an excuse to target certain white people throughout the history of the U.S. White abolitionists who opposed slavery were subject to violence along with blacks in the Cincinnati riots of 1836. During Reconstruction, Northerners who supported black rights could be attacked and killed—The KKK killed white and black civil rights workers. Gone With the Wind gleefully recounts the murder of a Yankee official during Reconstruction who dared tell black people they could marry whites. For that matter, whites who did want to marry blacks, like Richard Loving, faced harassment and discrimination. Even beyond that, Ta-Nehisi Coates points out that politicians who’ve been associated with black causes, whether the Republican Party before the Civil War or the Democratic Party in more recent years, have been subject to racist attacks. As Coates says, “Abraham Lincoln’s light skin did not save him from a racist political attack, any more than it saved him from a racist assassination plot.”

Piper (in real life and in the TV show) wasn’t a civil rights worker or a political figure. But the fact remains that our prison system, the largest in the world, has been justified and sustained by a cultural commitment to policing people of color. As many historians have argued, the war on crime was inaugurated by politicians like Barry Goldwater and Richard Nixon, who argued that civil rights demonstrations and movements were leading to a breakdown of law and order, the solution for which was more cops and more prisons. The result was an ongoing rhetoric of race-baiting around crime and imprisonment, exemplified by George H.W. Bush’s notorious 1988 Willie Horton ad. That rhetoric in turn fueled a 700 percent growth in prison population between 1970 and 2005.

In 2010 blacks were incarcerated at a rate of 2207 per 100,000 people and Latinos at the rate of 966 per 100,000, as opposed to only 380 per 100,000 for whites.

Nonetheless, there are still a lot of white people in prison: white males were 32.9 percent of the prison population in 2008, as opposed to 35.4 percent black males. And a large number of those whites were in prison for the same reason as blacks—because America, in an excess of racial panic, has built a massive drug war and a massive prison system in an effort to police and control black people. America’s prison system disproportionately affects black people, through sentencing disparities for crack and other systemic biases. But the drug war machinery sometimes, almost incidentally, catches white people in its gears as well. The white rate of incarceration in the U.S., at 380 per 100,000, is still in the top 20 incarceration rates worldwide, and is twice as high as rates in England and Wales.

Since the moment it enshrined slavery in its Constitution, American authoritarianism has been built upon racism. Piper may be privileged in some ways, but at least for a while that racist authoritarianism has gotten her by the blonde locks as surely as it’s got her cellmates. Once you’ve built your prison, you can put anyone in it. Which is just one way that racism has made America less free, especially for black people, but not for them alone.