[This has been cross-posted from The Middle Spaces.]

I wrote my master’s thesis on Jonathan Lethem’s The Fortress of Solitude exploring the seriality of narratives of place and race in the ongoing work of performing identity. Superhero comic books (as the title might suggest) were a big part of that work, and a significantly revised version of that work towards my MA became a chapter of my dissertation and informed the conceptual framework for the whole project. As such, I tend to keep a look out for comics that explore the relationship of place and identity, either explicitly or implicitly, and there is probably no greater example of this relationship than Marvel’s Ben Grimm (aka The Thing) and his old neighborhood, Yancy Street.

I wrote my master’s thesis on Jonathan Lethem’s The Fortress of Solitude exploring the seriality of narratives of place and race in the ongoing work of performing identity. Superhero comic books (as the title might suggest) were a big part of that work, and a significantly revised version of that work towards my MA became a chapter of my dissertation and informed the conceptual framework for the whole project. As such, I tend to keep a look out for comics that explore the relationship of place and identity, either explicitly or implicitly, and there is probably no greater example of this relationship than Marvel’s Ben Grimm (aka The Thing) and his old neighborhood, Yancy Street.

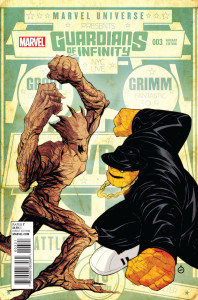

It was because of this interest that I picked up Guardians of Infinity #3. I had read online that it featured a story about the Thing and Groot (from Guardians of the Galaxy) returning to Yancy Street, and something about the latter being mistaken for a Ceiba Tree, the national tree of Puerto Rico, and a significant symbol of continuity with the pre-Columbian people on that island and in many places in Latin America.

I don’t know why the Guardians of the Galaxy comic is currently named Guardians of Infinity, or maybe it is a different title altogether that just features some of the same characters. I don’t really care about the series, but I do care about representations of Puerto Rico and Puerto Rican history and culture in comics. I even got that quirky, but well-characterized, 2008 Los Quatro Fantasticos one-shot that was sold in English and Spanish and features the FF traveling to the island to go up against la chupacabra. (One day I may write about it).

It turns out that “Yo Soy Groot” is a back-up story. I like a good back-up story, and better a one-shot story that has nothing to do with continuity than one that gets me sucked into buying a title I feel lukewarm at best about. The story is co-written by Darryl “DMC” McDaniels (of Run-DMC fame) and Edgardo Miranda-Rodriguez, who usually work together on Darryl Makes Comics. It is drawn by Nelson Faro DeCastro.

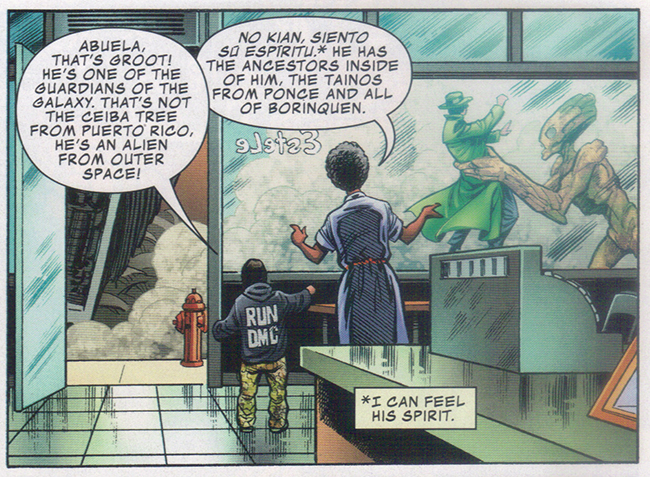

There isn’t much to the story. The Thing comes back to Earth getting a day off from the Guardians of the Galaxy (his new team ever since the Fantastic Four ceased to be after the events of the third and most recent bout of the Secret Wars) to run some errands and brings Groot with him. He’s visiting Yancy Street to load up on his favorite knishes, when Plant Man attacks, threatening to tear down civilization with snake-like plant monsters growing out the city’s green spaces. Plant Man has no motivation other than returning New York City to the wild, and for some reason the Marvel analog of the Lower East Side is where he chooses to begin. At first Grimm and Groot seem to make quick work of the plant monster and its master, but Plant Man takes control of Groot and sends him on a rampage. The Thing is sent flying by a mighty blow and serendipitously lands in front of the knish-shop where he was to complete his errands. Meanwhile, una abuelita nearby recognizes Groot as the Ceiba Tree and claims the souls of her Puerto Rican Taíno ancestors are in him. She is basically able to talk him into resisting Plant Man’s control, which is demonstrated nicely by Groot adapting his signature (and only) phrase to “Yo soy Groot!” The Thing returns. Plant Man is defeated. The two heroes take a selfie con la abuela and her grandson. The end.

The story has got its moments, but it isn’t great.

It has kind of a kiddie feel, which would be fine, except the story is in a comic that is decidedly not for “kiddies.” There is something about the way the whole first part of the story has the Thing spouting feel good non-sequiturs about the neighborhood that reads like a picture book, and the way the story conveys cultural information is similarly stilted.

The most potent aspect of “Yo Soy Groot,” however, is the woman’s identification of Groot with the Ceiba tree. I know little about the modern Groot’s origins—I do know he was originally an invading alien monster in an early issue of Tales to Astonish—but I like that the story doesn’t try to re-tell or ret-con origins to connect Groot to Puerto Rican tradition. Identity isn’t originary, and who is to say that ancestral spirits cannot travel the cosmos and inhabit some alien ceiba? It is a clever connection to make, because all you need do is see a picture of the 500-year-old ceiba tree in Ponce’s Parque de la Ceiba to see the resemblance to Groot.

The most potent aspect of “Yo Soy Groot,” however, is the woman’s identification of Groot with the Ceiba tree. I know little about the modern Groot’s origins—I do know he was originally an invading alien monster in an early issue of Tales to Astonish—but I like that the story doesn’t try to re-tell or ret-con origins to connect Groot to Puerto Rican tradition. Identity isn’t originary, and who is to say that ancestral spirits cannot travel the cosmos and inhabit some alien ceiba? It is a clever connection to make, because all you need do is see a picture of the 500-year-old ceiba tree in Ponce’s Parque de la Ceiba to see the resemblance to Groot.

Regardless, what I don’t like about the story is the way it falls into faulty tradition of translating culture through folk customs. I frequently find myself wondering if ostensibly positive representations of Puerto Rican (or any “ethnic”) culture or post-colonial people have to be connected to folk tales and spiritual beliefs, because it seems so common a way to note “authenticity.”

I understand the resistant politics that call on colonized people to support and, if necessary, recreate, pre-Columbian folk traditions or traditions that arose in response to colonial power, but I hate—to use Edward Said’s term—the schematic authority of such narratives and their nearly anthropological expression of cultural meaning. It strikes me as clunky and limiting—the kind of defining that looks for authenticity in a static reading of history that cannot exist except as a repeatedly reinvigorated and rehabilitated unified narrative that erases difference.

Still, I like the abuelita. I like her Afro-Puerto Rican features. Me gusta que esa negra tiene orgullo. I appreciate her trust in her beliefs enough to charge out at a rampaging Groot, and risk being crushed to death to talk some sense into him the way que solamente una abuela puede (though I am really glad they didn’t have her go after Groot with a chancla). I like that she and her grandson (somewhat belatedly) give a sense of the changing face of Yancy Street, so that is does not remain an ahistorical enclave untouched since Jack Kirby lived in its real world allegory. Sure, the bilingual dialog was stilted. It did that very unnatural-sounding thing where characters repeat an important word in both languages. It is an annoying tick of too much bilingual dialog, especially in Spanish (or maybe I just think so because I speak it and read it). When Grimm goes to get the knishes, the fabrikant tells him, Zayt mir gezunt un shtark, and while a footnote translates the expression, there is no cultural transliteration (though this video suggests there might be more about that saying that needs explaining) or stilted representation of code-switching. So maybe I am right about the way Spanish bilingualism is typically shown.

Still, I like the abuelita. I like her Afro-Puerto Rican features. Me gusta que esa negra tiene orgullo. I appreciate her trust in her beliefs enough to charge out at a rampaging Groot, and risk being crushed to death to talk some sense into him the way que solamente una abuela puede (though I am really glad they didn’t have her go after Groot with a chancla). I like that she and her grandson (somewhat belatedly) give a sense of the changing face of Yancy Street, so that is does not remain an ahistorical enclave untouched since Jack Kirby lived in its real world allegory. Sure, the bilingual dialog was stilted. It did that very unnatural-sounding thing where characters repeat an important word in both languages. It is an annoying tick of too much bilingual dialog, especially in Spanish (or maybe I just think so because I speak it and read it). When Grimm goes to get the knishes, the fabrikant tells him, Zayt mir gezunt un shtark, and while a footnote translates the expression, there is no cultural transliteration (though this video suggests there might be more about that saying that needs explaining) or stilted representation of code-switching. So maybe I am right about the way Spanish bilingualism is typically shown.

I called this latinified representation “belated” above, because of course the Lower East Side, despite being strongly associated with its Jewish immigrant heritage, has been integrated with African-Americans and Puerto Ricans since after World War II, and by the time of the Fantastic Four’s rocket flight, suffered from (according to The Encyclopedia of New York City) “persistent poverty, crime, drugs, and abandoned housing” (769-770). Still, Yancy St. is not the actual Lower East Side, and serves the ideal representation of the “authentic” ethnic neighborhood, not a historical representation of an immigrant neighborhood. It can take time for a pop culture to get past its ahistorical ideas about peoples and places.

What is admirable about the representation of Yancy Street in Guardians of Infinity #3 is that the traditionally Jewish neighborhood remains demarked by the Yiddish and the yarmulke-wearing knish-maker despite its changing face as represented by the unnamed abuela (according to an article about the story she is called Estela, but it is not mentioned in the narrative). The story, despite its shortcomings, invites readers to imagine a culturally diverse neighborhood that grows more heterogeneous over time, but remains stamped by the communities that have moved through it. This Yancy Street represents a utopian desire for cosmopolitan urban neighborhoods cognizant of their history—through customs, landmarks, local slang and dialects, memories—while allowing for belonging across difference. It doesn’t matter if those differences are Puerto Ricans in a formerly Jewish neighborhood or space-faring intelligent trees and Taíno spirits.

As such, “Yo Soy Groot” imagines a decidedly different Yancy St. from the one frequently used to define or explore some aspect of Ben Grimm’s identity by having him return to his origins through conflict with more recent incarnations of his old crew, The Yancy Street Gang.

And here is where I articulate what might seem like a contradictory opinion: when it comes to Aunt Petunia’s favorite nephew, Benjamin Grimm, aka the ever lovin’ blue-eyed Thing, I can’t help but feel that his origins in the Marvel version of the Depression Era Lower East Side largely define him as the character that I love. I know that just above I wrote that identity is not originary, but I meant that broadly, in defining authentic belonging to a culture. Individuals (re)collect clusters and fragments of histories, memory, stories, customs and social networks to form narratives of belonging that contain an imagined relationship to ultimately inaccessible culture. In the case of The Thing, Yancy Street is one of those clusters, framed by a geographic location that is imaginably distinct, but simultaneously overlapped by heterogeneous spaces and notions of history. Thus, it can both be “a Jewish neighborhood,” (even as it once was called “Little Germany”) and be home to the unnamed abuela, who does not feel it incongruous when the manifestation of a Puerto Rican cultural icon appears on her block. To me the voice of the Thing is the voice of Jimmy Durante—something Stan Lee claimed in a 1997 Stan Lee’s Soapbox, but that I, among many others, could hear in the character’s sayings and cadence (and in the 1979 cartoon Fred and Barney Meet the Thing). Durante, of course, like Jack Kirby was another LES boy made good, and though he was a Catholic Italian-American, and not Jewish, his Yiddish nickname—Schnozzola—suggests the hybridity of immigrant New York.

And here is where I articulate what might seem like a contradictory opinion: when it comes to Aunt Petunia’s favorite nephew, Benjamin Grimm, aka the ever lovin’ blue-eyed Thing, I can’t help but feel that his origins in the Marvel version of the Depression Era Lower East Side largely define him as the character that I love. I know that just above I wrote that identity is not originary, but I meant that broadly, in defining authentic belonging to a culture. Individuals (re)collect clusters and fragments of histories, memory, stories, customs and social networks to form narratives of belonging that contain an imagined relationship to ultimately inaccessible culture. In the case of The Thing, Yancy Street is one of those clusters, framed by a geographic location that is imaginably distinct, but simultaneously overlapped by heterogeneous spaces and notions of history. Thus, it can both be “a Jewish neighborhood,” (even as it once was called “Little Germany”) and be home to the unnamed abuela, who does not feel it incongruous when the manifestation of a Puerto Rican cultural icon appears on her block. To me the voice of the Thing is the voice of Jimmy Durante—something Stan Lee claimed in a 1997 Stan Lee’s Soapbox, but that I, among many others, could hear in the character’s sayings and cadence (and in the 1979 cartoon Fred and Barney Meet the Thing). Durante, of course, like Jack Kirby was another LES boy made good, and though he was a Catholic Italian-American, and not Jewish, his Yiddish nickname—Schnozzola—suggests the hybridity of immigrant New York.

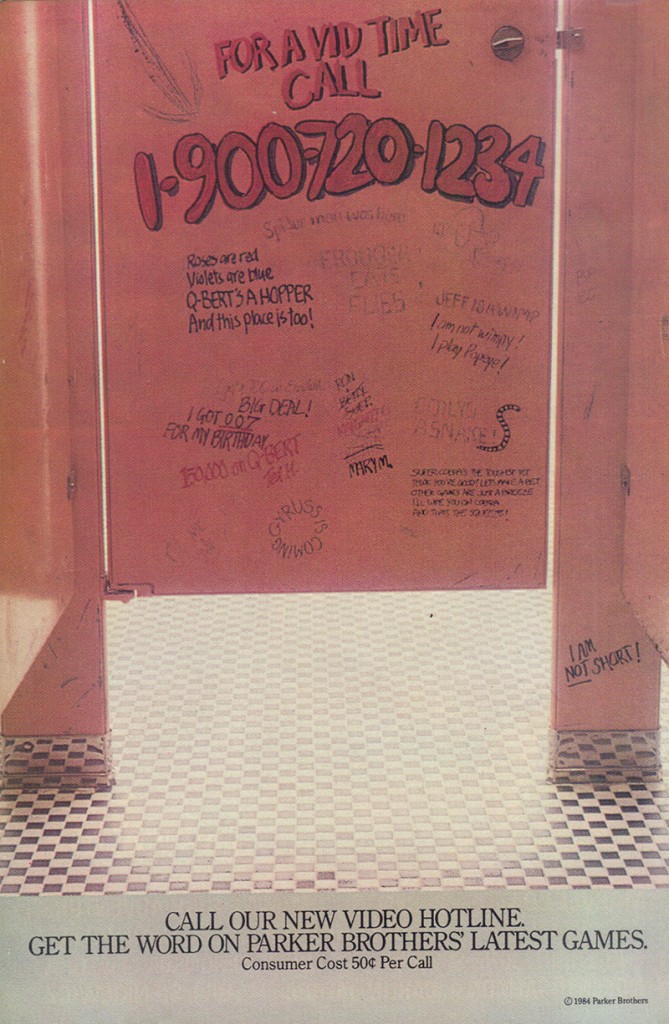

Despite these heterotopian possibilities, the Thing present in “Yo Soy Groot” feels off. It is almost as if he is DMC’s Marvel Comics avatar, robbed of his history. He wears the classic black hat, black leather trench coat and Adidas that defined Run-DMC’s signature look, and throughout the story he spouts classic rhymes and feel good truisms. So he while posing cross-armed he says, “Ya gotta take of and love the kids in these mean streets!” He raps a bit of Grandmaster Flash’s “New York New York.” He also drops phrases like “Keep it 100, fellas!” and “pop off.” None of this sounds like the Thing to me. Maybe it makes sense to make him younger, since if Ben Grimm really had grown up in the Depression Era and fought in World War II he’d be in his 80s or 90s. Maybe he could be made a Baby Boomer or even one of those Gen-Xers that were among the first to reach their 50s and remembers well the blight of 1970s and 80s—it wasn’t the Great Depression, but nevertheless represents economic wastelands scattered throughout urban America. But it is not the serial comics distortion of time that makes this version of the Thing seem off. It is the lack of tension between his shifting identity and static notions of the old neighborhood. In other words, what I may be sensing in this story is how it fails the character while serving the representation of the place and its heterotopic ideals.

As such, I’ve chosen three older instances of Grimm’s return to Yancy St. to consider his relationship to it over time and how that relationship shapes his identity by favoring particular aspects of it.

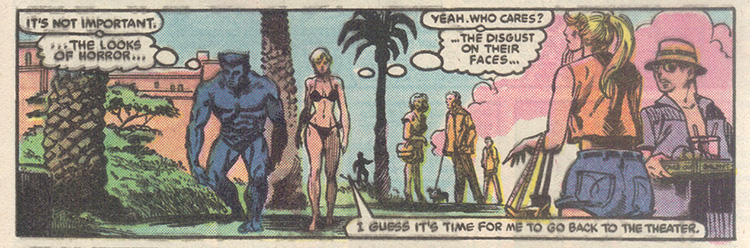

In 1963’s Fantastic Four vol. 1, #15 (written, drawn & plotted by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby), The Thing is depicted down on Yancy Street calling out its namesake gang for a mocking drawing of him in a tutu, calling him a sissy. Ramzi Fawaz has a great reading of the panel in The New Mutants: Superheroes and the Radical Imagination of American Comics, in which he connects the gang’s feminization of The Thing to how his relatively new rocky form draws attention to his need for him to perform “hard masculinity” to overcome the inhumanity of his embodiment. As Fawaz writes, “[Due to his rocky body,] Ben is paradoxically unable to perform the assumed functions of hard masculinity—obtaining a job, getting married, having sex—which makes him a ‘sissy’” (77). In the scene Yancy Street, Ben’s origins, become synonymous with a normative and naturalized idea of a post-war American masculinity performed through territoriality and violence. His new position relative to his old neighborhood (as both celebrity and inhuman monster) highlights his distinctness from those normative ideas of manhood, even as he sometimes performs exaggerated versions of it through violent outbursts. The neurosis that Fawaz identifies in Thing’s outsider condition that also manifests in self-deprecating humor about his monstrousness and self-pity over his lack of desirability resonates with the expectations of his home neighborhood, as in a much later story written by Dan Slott, where in flashback Grimm’s late older brother (the original leader of the Yancy St. Gang) says. “All we got is this few square blocks of #$*%…But it’s our #$*%! And when we fight for it, it means something” (emphasis his). The territoriality and sense of betrayal at Grimm’s new midtown address (the Baxter Building) is a response to class-based insecurity even as it reinforces anxiety over their difference. As a child of Yancy Street, Grimm feels these pressures and insecurities as well, while reveling in the androgynous gender play his embodiment allows him.

In 1963’s Fantastic Four vol. 1, #15 (written, drawn & plotted by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby), The Thing is depicted down on Yancy Street calling out its namesake gang for a mocking drawing of him in a tutu, calling him a sissy. Ramzi Fawaz has a great reading of the panel in The New Mutants: Superheroes and the Radical Imagination of American Comics, in which he connects the gang’s feminization of The Thing to how his relatively new rocky form draws attention to his need for him to perform “hard masculinity” to overcome the inhumanity of his embodiment. As Fawaz writes, “[Due to his rocky body,] Ben is paradoxically unable to perform the assumed functions of hard masculinity—obtaining a job, getting married, having sex—which makes him a ‘sissy’” (77). In the scene Yancy Street, Ben’s origins, become synonymous with a normative and naturalized idea of a post-war American masculinity performed through territoriality and violence. His new position relative to his old neighborhood (as both celebrity and inhuman monster) highlights his distinctness from those normative ideas of manhood, even as he sometimes performs exaggerated versions of it through violent outbursts. The neurosis that Fawaz identifies in Thing’s outsider condition that also manifests in self-deprecating humor about his monstrousness and self-pity over his lack of desirability resonates with the expectations of his home neighborhood, as in a much later story written by Dan Slott, where in flashback Grimm’s late older brother (the original leader of the Yancy St. Gang) says. “All we got is this few square blocks of #$*%…But it’s our #$*%! And when we fight for it, it means something” (emphasis his). The territoriality and sense of betrayal at Grimm’s new midtown address (the Baxter Building) is a response to class-based insecurity even as it reinforces anxiety over their difference. As a child of Yancy Street, Grimm feels these pressures and insecurities as well, while reveling in the androgynous gender play his embodiment allows him.

And yet, as Fawaz rightly points out, it is Ben Grimm’s neurosis that readers tend to identify with. Despite his complex and angry reactions to feeling “trapped” in his gender indeterminate rocky body, the stories of the Fantastic Four provide a setting where that very body provides him literal power in the form of physical strength, but also in its ability to connect him to a growing network of characters in the Marvel Universe who have been “rendered…sexual deviants or species outcasts” (78-9). As noted by Marvel’s wide use of the Thing in promotional material throughout the 60s and 70s (79), the Thing was popular, and not for the ways he recapitulated hard masculinity, but because of the way he subverts it through the expressions of sensitivity, insecurity and love. His relationship with Yancy Street in this case provides a touchstone for that resistance.

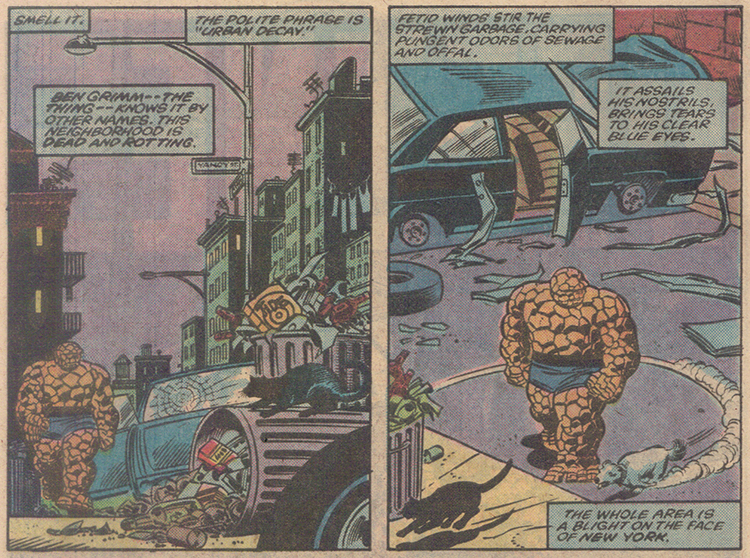

In The Thing vol.1, #1 (1983), written by John Byrne (with pencils and inks by Ron Wilson and Joe Sinnot), Ben Grimm returns to a rundown Yancy Street to find the building he grew up in now abandoned and used as a kind of headquarters the latest iteration of the Yancy Street Gang. He uses his connection to the block to give the kids some advice for staying alive and out of trouble at the behest of one of the kids’ father. This issue calls for a sharp reader to connect the setting of Grimm’s Depression Era upbringing to the grim straits of late 70s/early 80s New York City. Here in 80s superhero comics fashion, the history of Yancy Street is explicitly deracialized and poverty is divorced from public policy. Byrne writes narration where Grimm explains the gang conflict of his era as not “black against white” or “rich against poor.” The accompanying panel depicts two gangs of poor white kids rumbling, and the narration explains that these “poor punks” have “so little to lose” they “lash out” at other poor and hungry kids. Grimm’s identity is associated with abject poverty through his connection to place, his Depression Era childhood echoing the urban blight of Reagan America. The issue has a depressingly real unresolved ending with the young Yancy Streeters rejecting Ben’s story of warning about his own brother’s death as a result of gang violence, and Ben’s own near failure to escape that same fate. To the Yancy Street kids, Ben Grimm is “a sell-out” who “broke the odds” and got to live “the soft life.” The gang leader is so embedded in his ideological narrative of authenticity he refuses to believe downcast Thing when told, “There’s a lot more ta life than Yancy Street.” Here the Thing’s identity, while still shaped by his origins is decidedly marked by his ability to escape it, a desire to help others do the same, and his overall sensitivity. Twenty years after that first Yancy Street appearance, this sensitivity is a defining part of the Thing, who is depicted as a lot less prone to outbursts of frustration and violence. Instead, he is frequently depicted as sweet to children and the developmentally disabled (as in his “nephew” Franklin and his one-time ward Wundarr), and as having a fear of scary stories, horror movies and things of occult origin (there are too many examples in issues of Marvel Two-in-One to even go into them). Even as recently as 2005’s Civil War, rather than participate in the inter-superhero conflict and fight his friends, Ben Grimm declares his neutrality and absconds to France for a time.

In The Thing vol.1, #1 (1983), written by John Byrne (with pencils and inks by Ron Wilson and Joe Sinnot), Ben Grimm returns to a rundown Yancy Street to find the building he grew up in now abandoned and used as a kind of headquarters the latest iteration of the Yancy Street Gang. He uses his connection to the block to give the kids some advice for staying alive and out of trouble at the behest of one of the kids’ father. This issue calls for a sharp reader to connect the setting of Grimm’s Depression Era upbringing to the grim straits of late 70s/early 80s New York City. Here in 80s superhero comics fashion, the history of Yancy Street is explicitly deracialized and poverty is divorced from public policy. Byrne writes narration where Grimm explains the gang conflict of his era as not “black against white” or “rich against poor.” The accompanying panel depicts two gangs of poor white kids rumbling, and the narration explains that these “poor punks” have “so little to lose” they “lash out” at other poor and hungry kids. Grimm’s identity is associated with abject poverty through his connection to place, his Depression Era childhood echoing the urban blight of Reagan America. The issue has a depressingly real unresolved ending with the young Yancy Streeters rejecting Ben’s story of warning about his own brother’s death as a result of gang violence, and Ben’s own near failure to escape that same fate. To the Yancy Street kids, Ben Grimm is “a sell-out” who “broke the odds” and got to live “the soft life.” The gang leader is so embedded in his ideological narrative of authenticity he refuses to believe downcast Thing when told, “There’s a lot more ta life than Yancy Street.” Here the Thing’s identity, while still shaped by his origins is decidedly marked by his ability to escape it, a desire to help others do the same, and his overall sensitivity. Twenty years after that first Yancy Street appearance, this sensitivity is a defining part of the Thing, who is depicted as a lot less prone to outbursts of frustration and violence. Instead, he is frequently depicted as sweet to children and the developmentally disabled (as in his “nephew” Franklin and his one-time ward Wundarr), and as having a fear of scary stories, horror movies and things of occult origin (there are too many examples in issues of Marvel Two-in-One to even go into them). Even as recently as 2005’s Civil War, rather than participate in the inter-superhero conflict and fight his friends, Ben Grimm declares his neutrality and absconds to France for a time.

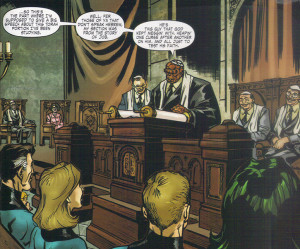

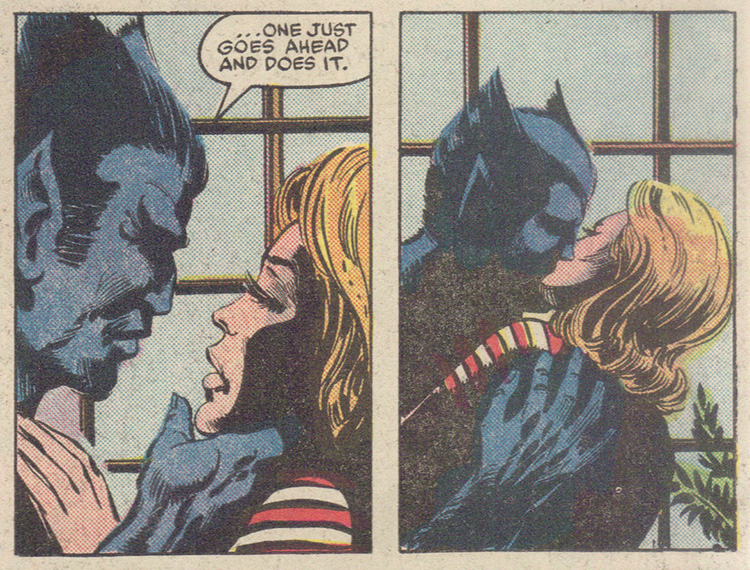

Twenty years later in the pages of the second volume of Thing’s solo book, Dan Slott uses Yancy Street to clearly establish the Jewish heritage that had long been part of the subtext of the character, but that was not explicitly stated until 2002. The story in issues #5 and #6 of this volume serves to once again negotiate a new aspect of Ben Grimm’s identity—his wealth—through a return to his old neighborhood. When he uses recently acquired billions to build a youth center on Yancy Street—tearing down derelict buildings and reshaping the neighborhood in the process—some of the locals are unimpressed, thinking that the Grimm Youth Center is a sign of the superhero’s inflated ego. However, later it is revealed it is named after Grimm’s late brother, Daniel Grimm, the original leader of the Yancy Street Gang, and the nod to their history gains the gang’s respect. After 40 years’ worth of issues across multiple titles where the Thing and the Yancy Street Gang were at odds, they come to a resolution of sorts, with their rivalry returning to friendly tone of pranks and insults. The story also features the character of “Old Man Sheckerberg,” a pawnbroker who has had a shop on the block since back when Ben Grimm was a kid, and who Ben used to steal from. The premise of the story has it that when not out saving the world, Ben is required to work for “Shecky” every Sunday until his debt is paid off. In actuality, since Ben could easily pay back a lot more than he could have ever owed (and tries to), the arrangement serves as a way of keeping Grimm tied to his former community. By working in the pawn shop he learns about the customers and the neighborhood news. And so, when in Thing vol. 2 #8 Shecky declares the debt finally paid, the Thing expresses his disappointment at being done, saying, “…I think I’m gonna miss it down here…You Yancy Streeters used to give me nuthin’ but grief, but since I been spendin’ alla’ my weekends here you’ve all made me feel like I belong again.” In order to cement that belonging, Shecky brings Ben to the local synagogue to meet the rabbi and arrange for the bar mitzvah that the Thing, delinquent kid that he was, never got to have.

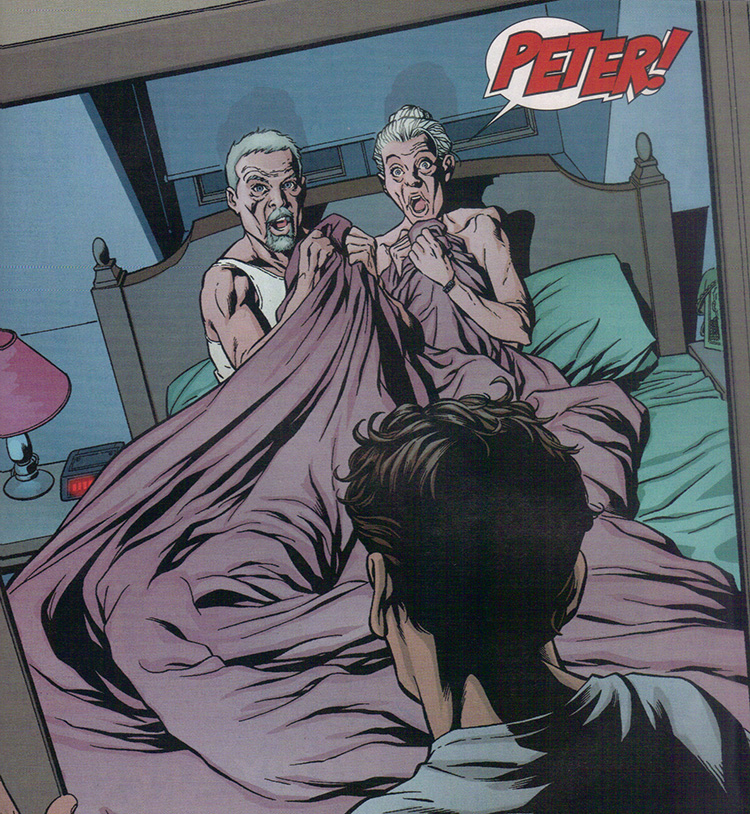

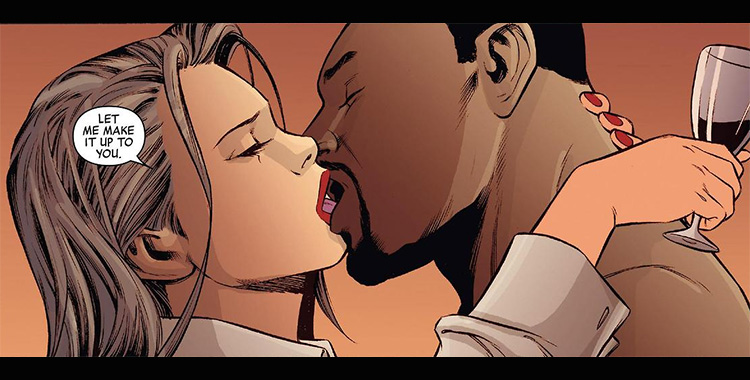

Ignoring the incongruity of the rabbi’s reasoning that since it’s been 13 years since Ben Grimm changed into the Thing and thus began “a new life” (shifting the FF’s 1961 historic rocket flight to 1993), this story brings his relationship to Yancy Street full circle to position his Jewish identity as a core part of the character. The story is a bit schmaltzy, but I appreciate its earnestness and was sincerely touched reading about his hard work studying Hebrew scripture and how all his superhero friends and neighborhood locals came to the ceremony. This is not to say that the story is not without its problems, the foremost being that Grimm’s achieving “manhood” concludes with a very strong intimation that he and Alicia Masters are going to have sex, which may not completely remove the productive gender ambiguity that Fawaz highlights in his work, but makes the community’s confirmation of his “manhood” seem like the Thing acquiescing to traditional notions of masculinity represented by his hood (as in Fantastic Four vol. 1, #15) and not the community accepting his gender-queerness.

Ignoring the incongruity of the rabbi’s reasoning that since it’s been 13 years since Ben Grimm changed into the Thing and thus began “a new life” (shifting the FF’s 1961 historic rocket flight to 1993), this story brings his relationship to Yancy Street full circle to position his Jewish identity as a core part of the character. The story is a bit schmaltzy, but I appreciate its earnestness and was sincerely touched reading about his hard work studying Hebrew scripture and how all his superhero friends and neighborhood locals came to the ceremony. This is not to say that the story is not without its problems, the foremost being that Grimm’s achieving “manhood” concludes with a very strong intimation that he and Alicia Masters are going to have sex, which may not completely remove the productive gender ambiguity that Fawaz highlights in his work, but makes the community’s confirmation of his “manhood” seem like the Thing acquiescing to traditional notions of masculinity represented by his hood (as in Fantastic Four vol. 1, #15) and not the community accepting his gender-queerness.

Returning to “Yo Soy Groot,” while its position as a back-up story means that it would not have enough room for exploring a more compelling conflict than the yawn-inducing Plant Man, there are other hints of a changing Yancy Street (still belatedly echoing the LES’s own changes) that could serve as productive tensions to explore without needing to oversimplify the neighborhood’s character or erase its diversity. In one panel a neighborhood bystander complains that the superhero fracas is going to make him late for his “micro-brewer symposium,” his scarf and beard presumably signaling his hipster identity. This suggests recent waves of gentrification whose economic restructuring leads to complex and conflicting narratives of neighborhood authenticity that erase or justify the displacement of poor and working-class people of color. (For a fantastic examination of how narratives of white ethnic neighborhoods are used to undergird gentrifying waves of upwardly mobile “returning” whites to urban neighborhoods in Brooklyn check out Suleiman Osman’s The Invention of Brownstone Brooklyn (2011)). In this case, the Thing’s long-term relationship with working class Yancy Street could serve as a new way to explore his identity against the tensions of yet another demographic shift.

It may be worth noting that Yancy Street is the setting for the new Moon Girl & Devil Dinosaur series (which is fantastic so far, btw) and is portrayed as gentrified and upwardly mobile, and with some racial diversity. It will be interesting to see the setting develop in new ways distinct from its legacy as part of The Thing’s origin story. However, having a racially diverse Yancy St. Gang beat up and run off by monkey-like cavemen who mug commuters makes me nervous about the connotations.

It may be worth noting that Yancy Street is the setting for the new Moon Girl & Devil Dinosaur series (which is fantastic so far, btw) and is portrayed as gentrified and upwardly mobile, and with some racial diversity. It will be interesting to see the setting develop in new ways distinct from its legacy as part of The Thing’s origin story. However, having a racially diverse Yancy St. Gang beat up and run off by monkey-like cavemen who mug commuters makes me nervous about the connotations.

Ultimately, the utopian desires I noted in the “Yo Soy Groot” story are laudable, but such a productive imagination should not erase the complexities and disjunctures that arise from that work and must be addressed to achieve such heterotopias, and that give stories a richness and texture beyond reinforcing ideals of diversity.

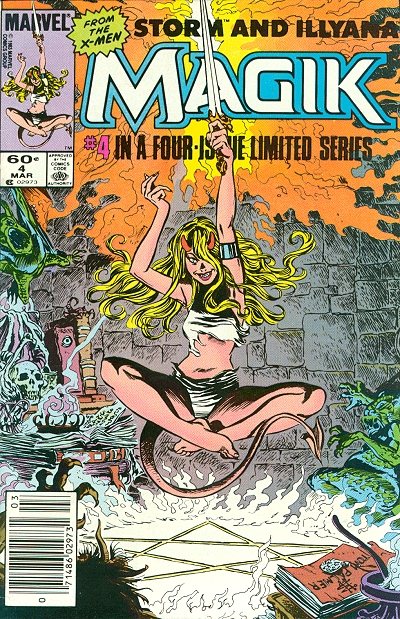

The most obvious example I can think of is Illyana Rasputin, aka Magik, of the New Mutants and later the X-Men. When she is kidnapped by Belasco, not only does he want to make her his bride, but as soon as she starts to get a little older she is depicted in her Darkchilde form mostly naked with a more developed body, little short shorts and a crop top, and with a come-hither look. When it comes to Ilyana, her arc from seven year old girl to New Mutant to X-Man is one that makes the subtext of uncontrollable dark magic and the dangers of female sexuality quite explicit. The whole Belasco’s bride thing makes it text, not sub-text. The way she is depicted now, after having reverted to her original age and then returned to her young adult form again, (dying and then returning), reinforces the possibilities opened up by her aging. She falls safely into the male gaze, from a position of taboo anticipation for her eventual desirability.

The most obvious example I can think of is Illyana Rasputin, aka Magik, of the New Mutants and later the X-Men. When she is kidnapped by Belasco, not only does he want to make her his bride, but as soon as she starts to get a little older she is depicted in her Darkchilde form mostly naked with a more developed body, little short shorts and a crop top, and with a come-hither look. When it comes to Ilyana, her arc from seven year old girl to New Mutant to X-Man is one that makes the subtext of uncontrollable dark magic and the dangers of female sexuality quite explicit. The whole Belasco’s bride thing makes it text, not sub-text. The way she is depicted now, after having reverted to her original age and then returned to her young adult form again, (dying and then returning), reinforces the possibilities opened up by her aging. She falls safely into the male gaze, from a position of taboo anticipation for her eventual desirability.