This is part of a roundtable on the work of Octavia Butler. The index to the roundtable is here.

__________

Octavia E. Butler, the most influential black American woman science fiction writer of the twentieth century, wrote to confront and understand power, an essential part of the human condition that she found entirely “fascinating.”[i] From the Patternist trilogy to Fledgling, her final published novel, Butler rarely flinched from using science fiction to ponder the depths to which people (and aliens) will go to ensure survival and growth. Stories of aliens colonizing war-ravished humans, masters subjugating slaves, men raping women, capitalists exploiting workers, and humans destroying the planet all speak clearly to this stubborn preoccupation with power. They also speak, of course, to what Butler often called the “Human Contradiction,” namely, the tendency to put our innate human “intelligence at the service of hierarchical behavior.”[ii] For Butler, humans are born with the capacity to be both extremely intelligent yet equally hierarchical – “characteristics” that she saw as evolutionarily necessary for human survival. Both traits can, if left alone, promote the survival of the species, but as the imaginary histories and futures reveal throughout Butler’s work, a different outcome unfolds, proving entirely that “the two together are lethal.”[iii]

Butler’s interest in the inner-workings of power owes a great deal to the fact that she experienced life from the margins. She was black, female, and (for most of her life) working class. Of course, to say that Butler wrote about power because she herself lacked it is somewhat obvious. As she has already observed: “one of the reasons I got into writing about power was because I grew up feeling like I didn’t have any.”[iv] Not so obvious, however, is the fact that Butler also wrote from another kind of margin: the genre of science fiction. Often relegated to the category of pulp fiction or pop culture, science fiction has endured what Samuel R. Delany has famously called a type of literary “ghettoization,” or the tendency to see science fiction “as a working-class kind of art,” that as such “is given the kind of short-shrift that working-class practices of art are traditionally given.”

Yet where there is power, there is resistance. Where there are centers, there are margins. And where there are ghettoes, there are stories of survival, resilience, and transformation. For although the lived realities of marginalization are not pretty, marginality can also generate counter-narratives and alternative perspectives. As bell hooks has already observed, marginality “offers the possibility of radical perspectives from which to see and create, to imagine alternatives, new worlds.”[v] And what other genre than science fiction is more equipped to explore radical – even alien – perspectives and wield alternatives to the status quo? It is no wonder Octavia Butler, a self-described introvert and a woman of color, was drawn to science fiction, a genre that she believed attracted “the out kids…People who are, or were, rejects.”[vi]

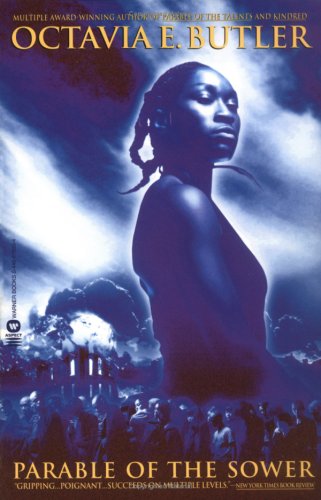

The sheer power of Butler’s interest in power emerges with stunning vividness in Parable of the Sower, my personal favorite of all her novels. Like so many post-apocalyptic cyberpunk texts, Parable begins after the fall of civilization as we in the late twentieth century U.S. have come to know it. Gone are the middle-class, basic social services (all of which have been privatized), and clean air and water. In their place is a United States in rapid decline where the majority of its subjects are living on the streets or as “debt” slaves in gated communities that function more like prisons than anything else. When I teach this novel, written the same year as the Rodney King riots in Los Angeles, my students often respond with despair. “This is too close to home,” as one put it last quarter. And, yet, this is precisely the response Butler wanted. She wrote it as a cautionary tale: “If we keep doing what we’re doing, here’s what we might end up with.”[vii]

With Parable, though, Butler not only mirrors for us the deadly consequences of unbridled capitalism and environmental destruction. All of this is there, sure. But what she also offers us is a paradigm for change and resistance. I am speaking, of course, of Earthseed, a new religion that Butler, through her protagonist Lauren, imagines as an alternative to dominant Western religions. In fact, Parable comprises two texts: the dystopian reality into which we are thrust and the “Book of Living,” Earthseed’s mission statement, snippets of which are placed at the beginning of most of the chapters. Rooted in a philosophical view that reveres nature, acknowledges the constant of change, and insists on the need for collaboration and community, Earthseed is Butler’s alternative to Christian fundamentalism and its tendency to subordinate the creative and transformative potential of human action to an authoritative, patriarchal, and ultimately oppressive Christian God. With Earthseed, prayer gives way to practice, belief is always attended by action, and Change is both positive and inevitable:

As wind,

As water,

As fire,

As life,

God

Is both creative and destructive,

Demanding and yielding,

Sculptor and clay.

God is infinite Potential.

God is Change.[viii]

Here, in the midst of what can only be described as a type of hell on Earth, Butler articulates a counter-narrative. Here, despite her belief that humanity is innately prone to self-destruction – remember her thing for ‘power’ – Butler dares to imagine an alternative. And this alternative is not outside of us or from the outside: it is a return to our potential to create, to shape, and to change.

In sum, Octavia Butler has left a mark not only because she was the first black woman science fiction writer to make a name for herself, or because she is the first science fiction writer – male or female, black or white – to win the prestigious MacArthur “Genius” Grant. She has left her mark because through stories like Parable Butler has proven that marginality can be productive, powerful, and transformative. For although she wrote after the steady decline of the Civil Rights era and during a time (1980s-1990s) in which the black underclass grew exponentially – as it continues to do so today – Butler never ended at hopelessness. Like her marginalized black women protagonists, who always seem to be drawn to writing and collaboration, Octavia Butler is the ultimate ‘radical’ postmodernist whose stories provide a safe space to question, shape, and transform the worlds within and without us.

_________

[i] Conversations with Octavia Butler, 173

[ii] Lilith’s Brood, 467

[iii] ibid., 37

[iv] Conversations, 173

[v] bell hooks, “Marginality as Site of Resistance,” 341

[vi] Conversations, 5

[vii] Conversations, 167

[viii] Parable of the Sower, 270