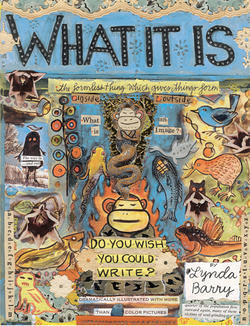

I published this in Poor Mojo’s Almanac a while back. I was thinking about it again in the context of our ongoing discussion of comics, reading, Lynda Barry, and pedagogy (parts of said conversation being here and here and here. Anyway, I thought I’d reprint it, and then talk a little about how I wrote it and (generalizing wildly) about how people create.

_____________________

Once upon a time there was a beautiful girl named Lorna, who lived with her mother in a house in the woods. Lorna was so beautiful that everyone who saw her fell in love with her. This was a nuisance; she couldn’t go to the stream to get a drink of water without getting twenty marriage proposals, and it was hard to feed the hens when the lawn was covered with young men kneeling and weeping. Lorna got so fed up that she didn’t even want to leave the house, and when she did leave it she’d have to put a bag over her head, which made it hard to see. Her mother, who was old and wrinkled and had an odd sense of humor, would giggle when she saw Lorna walking around and bumping into things. But she did love her daughter, and she knew this sort of thing wouldn’t do for the long term. So she told Lorna, “When I die, and you must seek your fortune, take my skin and wear it to disguise your beauty.”

Eventually, Lorna’s mother died. Lorna did as she’d been told; she took her mother’s skin, clothed herself in it, and went off to seek her fortune. She enjoyed walking through the fields without a bag over her head and without having to dodge love-sick suitors, even though having to wear her mother’s skin was a little icky. Finally, after a long trek, Lorna reached a large castle. She knocked and the Prince who owned the castle came to the door. As it happened, he needed someone to watch his geese. Lorna took the job.

Lorna moved into a little hut near the castle. She might have lived happily ever after there tending the geese, except that her mother’s skin didn’t fit exactly right. During the day it was okay, but at night when she was trying to sleep it pinched and itched, and she discovered that if she wanted any sleep at all she had to remove it. So she put it at the foot of her bed. And in the morning the geese would poke their heads into her hut, and see her sleeping in her natural form. Then they’d fly into the air singing, “Honk! Lorna’s prettier than you think! Honk! Honk!”

One day the Prince happened to be up early wandering out in the fields. He heard the geese honking about Lorna, and he was curious. So he walked over to Lorna’s hut and saw her through the window just as she was about to put on her mother’s skin. “Oh, drat!” said Lorna. “Does this mean you’re going to fall in love with me now?” And of course it did. But the Prince was fairly handsome himself, and, to tell the truth, Lorna was tired of geese and of dead skin. So she married him, and after a while, as she got older, she grew less pretty, and started to look rather like her mother even without the skin. Eventually only the prince and the geese and her children loved her, and all the young men fell in love with somebody else. Which was perfectly all right with her.

__________________

So…like I said, I wrote this a while back. It was originally supposed to be part of a Composition and Grammar textbook I was working on for high school students taking courses by correspondence. I was doing a unit on narrative and was having students do writing based on fairy tales. I would give them a bare bones outline of the fairy tale plot (one or two sentences), and then tell them to expand the story (into three or four paragraphs). I provided several examples of expanded narratives, and the story above was one such. (I think we didn’t use it because my boss at the time felt the whole mother’s skin thing was too creepy…and maybe she had a point.)

Anyway. Thinking about writing this, and the exercise it was a part of, made me think of this comment by Dan Kois about Lynda Barry’s pedagogy:

As I mention in passing in the article, Lynda makes the case in her class that narrative structure — that is, one major component of the craft of storytelling — is a natural muscle that most humans have. The example she gives is the way you tell a story depending on whether you have one minute to tell it or ten minutes to tell it; she points out that it’s a natural tendency to construct the details of a story in a manner appropriate for the space that one has to fill.

The exercise I was doing — asking students to expand a fairy tale — is basically an exercise that Barry says is unnecessary, if I understand Dan correctly. Barry’s saying that people naturally know how to tell a story in the time (or space) allotted. It’s not an issue of craft (that is, learned ability) because it’s natural, like falling in a lake. If you have ten minutes to tell a story, you tell it in ten minutes. Simple as that.

So were all my efforts superfluous? I didn’t think so then…and now that I have a son, and am subjected to his narrative efforts all the time, I’m even less convinced. If you listen to small kids tell stories, the thing you notice is that they don’t know how to do it. There was a horrible period there, for example, where my son was obsessed with Garfield. He wanted the strips read to him all the time (which was bad enough), but he also wanted to explain and relay the strips to others. And he just couldn’t do it. He could see the strip in his mind, and he generally got the words right, but he couldn’t figure out what needed to be told when and how to a person who hadn’t seen the strip. The narrative would start and stutter and stop and go back again, and miss the joke and then he’d start over and you just wanted to claw your eyes out and curse the name of Garfield forevermore.

My son’s much, much better at narrative now…but it’s not because he got in touch with his natural essence. It’s because he’s read a lot more, and listened to people talk a lot more, and has internalized (some of) the rules and codes for creating stories. And it really is often “rules and codes” — he and his friends tell stories to each other, and they are obsessive about breaking their stories into chapters…and almost as obsessive about repeating the same story in the same way as it was originally told to them. And…my son actually explained to me at length at one point how he was going to write the back cover blurb for his book. Which maybe means he’s being corrupted by corporate culture, but as a doting father, I prefer to believe that his command of point-of-purchase advertising is instead a sign of increased narrative mastery.

Be that as it may…I think my version of the “Mamaskin” story itself also suggests that narrative is less a natural reflex than an acquired skill. Specifically, the story is put together from other stories. The basic plot, as I said, is taken from a folk tale. My retelling is also informed, obviously, by my generalized knowledge of folk tales, and of folk tale adaptations. Specifically, it’s probably more than a little touched by Patricia Wrede’s YA feminist Enchanted Forest series, with the smart, capable Princess Cimorene, who starts young but as the series goes along gets older and wiser.

The end of the my story, though, comes from here:

He, the one they recognised, no longer thought–his mind being so occupied–that love might still exist. With all that was happening at the time it’s understandable that the only thing they would tell of later was what he did, the incredible action he performed, which no one had seen before: the gesture of supplication, in which he threw himself down before them, imploring them not to show love. Alarmed by this and shaking they raised him to his feet. They interpreted his

impulsive behaviour in their own way, while at the same time forgiving him. He must have found it indescribably liberating to find that they’d all misunderstood him, despite his desperately explicit manner.

It was likely they’d let him stay. As the days passed he came to see more clearly that the love they were so vain about and which they secretly encouraged in one another did not affect him. He almost had to smile at the trouble they took and it became obvious that their concern for him could not amount to much.

What did they know about who he was? He was now so terribly difficult to love, and he felt there was only the One who was capable of it. But He was not yet willing.

That’s the conclusion of Rilke’s The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge, and one of my favorite passages in all of literature. And since I liked it so much, I stole it, which is more or less what writers do. (I also was thinking of this line from slightly earlier in Rilke’s narrative: ” The simple love of his sheep didn’t affect him; like light falling through clouds, it was scattered all about him and shimmered softly upon the meadows.” I love that.)

I’m not denying that there’s a personal element in my version of “Mamaskin” as well. Like Lorna (and lots of other people), I found marriage rather a relief. But I’d argue that (like Lorna’s again) the relief is itself a narrative one. When you’re in the story of romance, you’re in the story of romance; getting out of that is figuring a way to tell a different tale, which is closely related to living a different life.

Barry’s certainly right, then, that narrative is natural in the sense that it’s tied up with and into human lives. But the thing is that human lives aren’t very natural; we’re weird alien things, narratives grafted onto dyring animals. Figuring out what to do with this narrative that’s in us isn’t something you find naturally the way a bee locates a flower. It’s something you acquire like a baby learns to speak. That is, with a certain amount of struggle and tears, and with varying proficiency depending on numerous factors, including the quality of your teachers. Speech is a technology and a craft, and so, surely, is writing. And, as is generally the case with a craft, you get better at it by imitating models, practicing, and sometimes taking advice. There’s not any particular magic to it, except maybe the magic of not having any magic except the skins our parents have left us.

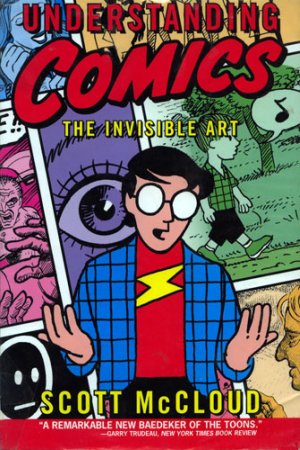

This essay was written in my first-year composition course at the George Washington University. University Writing Program faculty draw on a variety of disciplinary backgrounds (my Ph.D. is in American history, with current research on abolitionist visual rhetoric) to teach students to “enter the conversation” of academic research—to do detailed analysis and to engage existing scholarship rather than simply regurgitate it. This particular assignment arose out of the cross-fertilization that Craig Fischer argues is emblematic of comics scholarship, where academics, fans, practitioners, and popular critics seed each others’ ideas and produce more interesting work.

This essay was written in my first-year composition course at the George Washington University. University Writing Program faculty draw on a variety of disciplinary backgrounds (my Ph.D. is in American history, with current research on abolitionist visual rhetoric) to teach students to “enter the conversation” of academic research—to do detailed analysis and to engage existing scholarship rather than simply regurgitate it. This particular assignment arose out of the cross-fertilization that Craig Fischer argues is emblematic of comics scholarship, where academics, fans, practitioners, and popular critics seed each others’ ideas and produce more interesting work.