The cover of the 1965 Paperback Library novel Adam Link—Robot,

which collects Otto Binder’s Adam Link stories from the late 1930s and 1940s.

As I watched and enjoyed the new Spike Jonze science fiction film Her, I began to wonder, What would Otto Binder think of this? Although best known to comic book readers and scholars as the writer of Captain Marvel and Superman, Binder began his career as a science fiction writer, first in collaboration with his older brother Earl. The pair began publishing under the pen name Eando Binder (Earl and Otto) in the early 1930s. By the time “I, Robot,” the first in a popular series of adventures featuring the artificial man Adam Link, appeared in the January 1939 issue of Amazing Stories, Otto was writing on his own, but retained the Eando Binder byline.

In science fiction circles, Otto Binder’s best-known work remains the Adam Link series, which served as the inspiration for Isaac Asimov and for countless other writers exploring the idea of artificial intelligence. Over the course of his comic book career, Binder adapted some of the Adam Link stories for EC Comics in the 1950s and again for Warren Publishing’s Creepy in the 1960s. When Qiana invited me to contribute another guest post for Pencil Panel Page, I began to think again about her December 2011 essay “Can an EC Comic Make ‘You’ Black?” and what it might tell us about Otto Binder and Joe Orlando’s adaptation of “I, Robot” from Weird Science-Fantasy Number 27 (dated Jan.-Feb. 1955). In the EC version of “I, Robot,” Binder’s use of the second-person you places the reader in a complex position: as we read the story, do we identify with the hero, Adam Link, or with the violent mob threatening to destroy him?

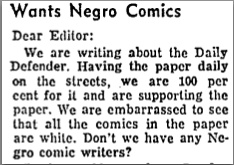

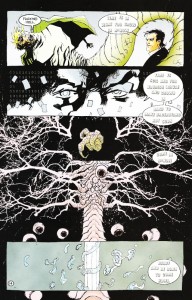

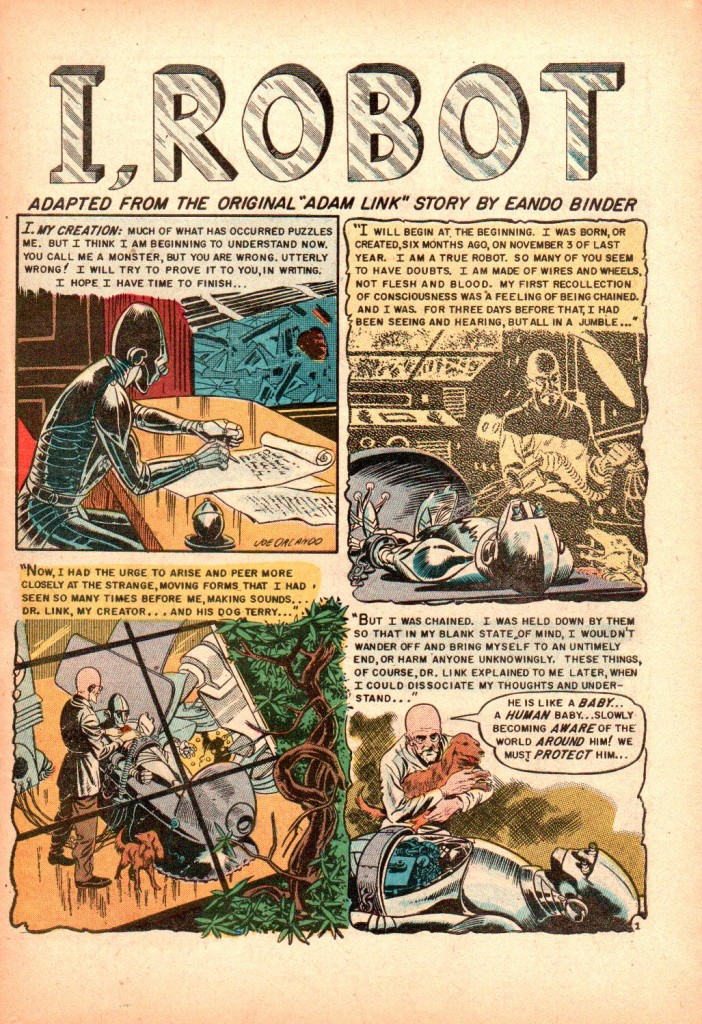

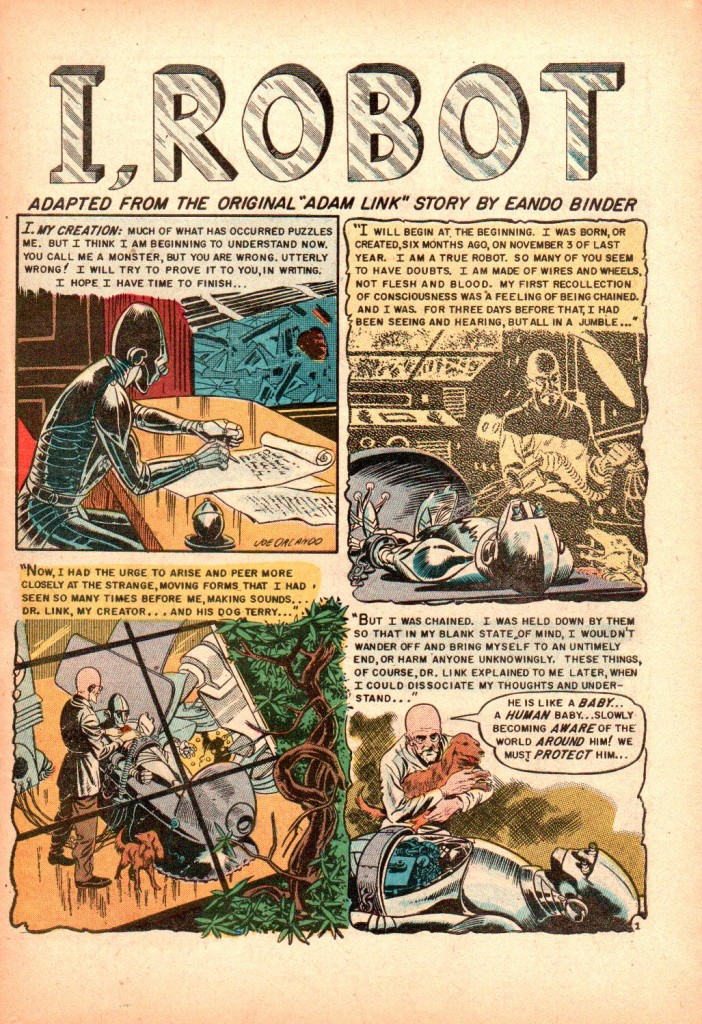

The first page of Otto Binder and Joe Orlando’s adaptation

of “I, Robot” for EC’s Weird Science-Fantasy Number 27 (Jan.-Feb. 1955). Colors by Marie Severin.

In a letter to science fiction fan and editor Sam Moskowitz dated October 4, 1952, Binder discusses the scripts he’s been producing for EC Comics. He explains that he’s “gotten into the groove on thinking of [science fiction] plots for them, even if they are more simplified and corny than what would go into a pulp.” Binder then appears to reconsider his summary of EC’s science fiction and fantasy comics and adds the following parenthetical comment:

(But a suggestion….pick up a copy of WEIRD FANTASY or WEIRD SCIENCE comics sometime and read them….the comics are not too far behind the pulps in well-plotted stories, believe it or not!)

In the early 1950s, after over a decade as a prolific comic book scripter, Binder was hoping to return to the science fiction market and was looking to Moskowitz, to whom he later left the bulk of his personal and professional correspondence, for advice and support. As Bill Schelly notes in his excellent biography Words of Wonder: The Life and Times of Otto Binder, the writer had to make some adjustments to his style when he began working for EC: “Binder’s job, as he saw it, was to emulate the writing style of Al Feldstein, who always put lots of lengthy captions into the scripts. This wasn’t Binder’s normal inclination, but he did his best.” As a freelance writer, Binder survived by adapting himself and his style to suit the requirements of his publisher and of his audience. As he explained in the letter to Moskowitz, “Now I have no prima-donna qualms about accepting ideas from an editor….it doesn’t violate my lone-wolf sensibilities. In fact, in the comics, editor and writer often whip up ideas between them.”

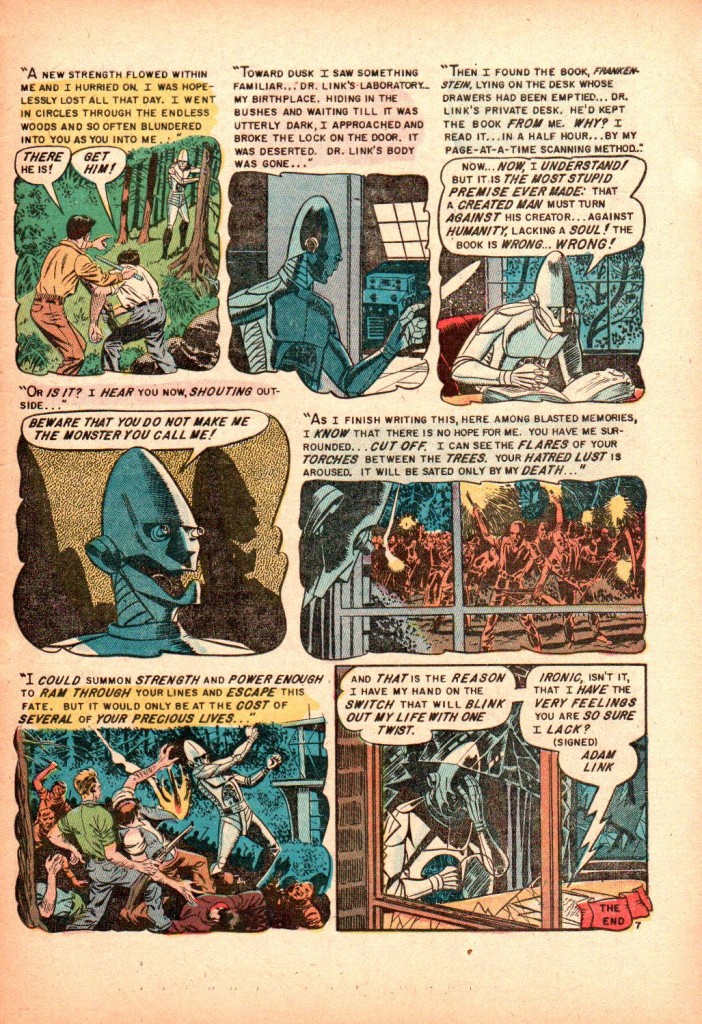

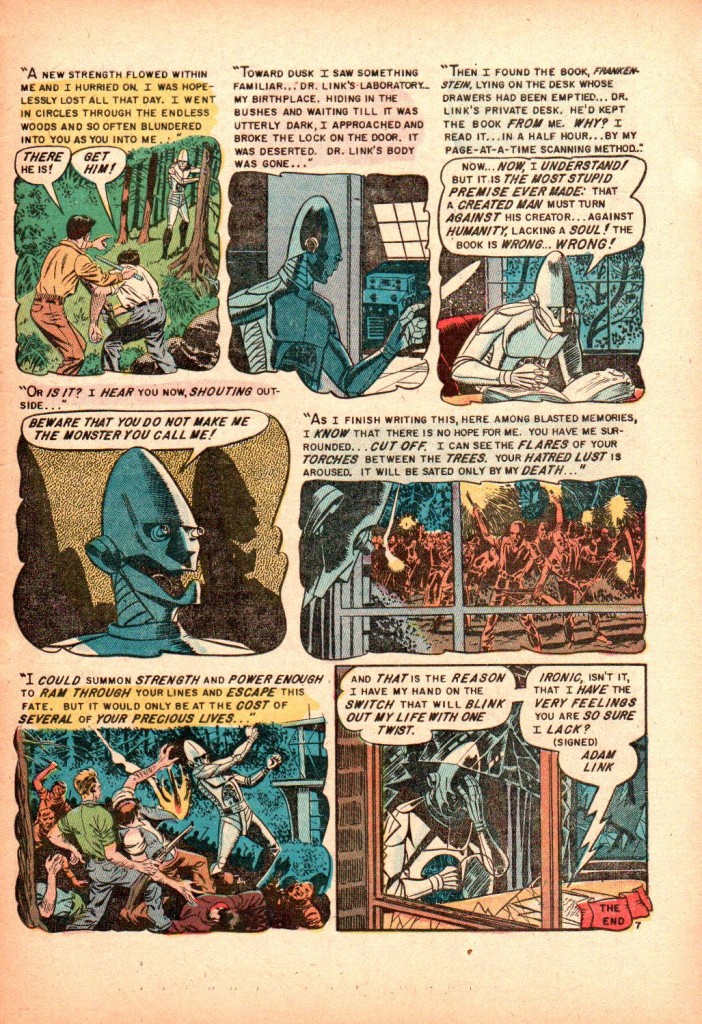

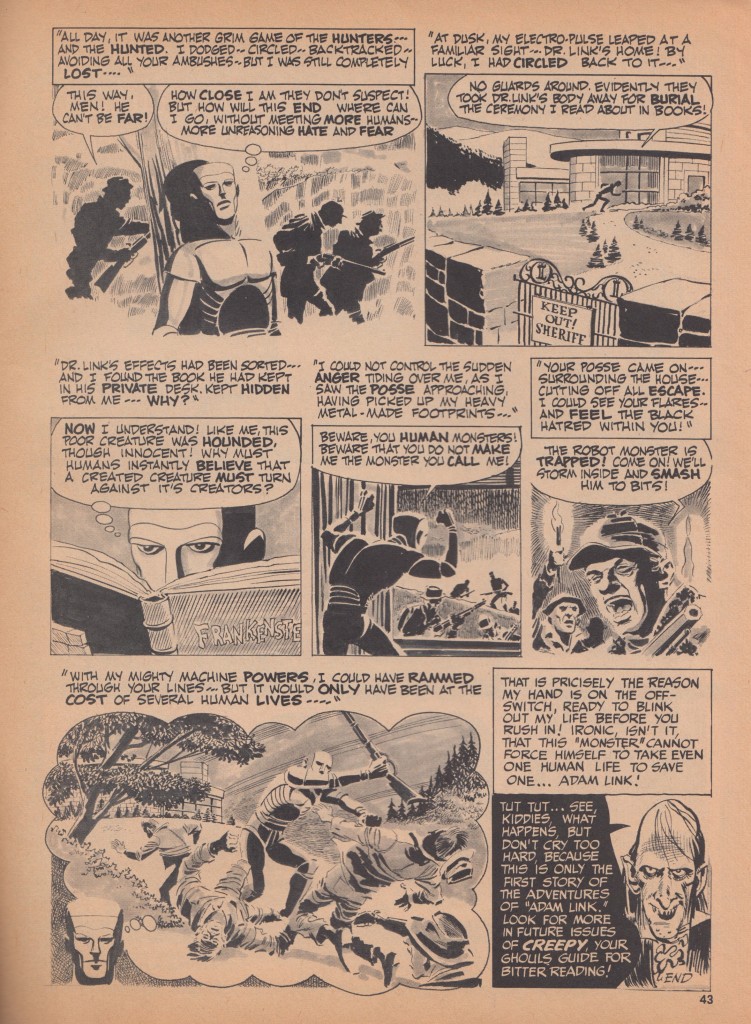

While in both the EC adaptation of “I, Robot” and in the 1939 original, Binder employs first person point-of-view as Adam Link tells the story of his creation, by the end of the Weird Science-Fantasy version, Binder shifts to the second-person as the robot addresses his tormentors—and, by extension, those of us reading the story. On the final page of the 1955 “I, Robot,” Adam Link, wrongly accused of murdering his creator and surrounded by an angry mob, exclaims, “Beware that you do not make me the monster you call me!” In his journal, he writes, “As I finish writing this, here among blasted memories, I know that there is no hope for me. You have me surrounded…cut off. I can see the flares of your torches between the trees. Your hatred lust is aroused. It will be sated only by my death…”

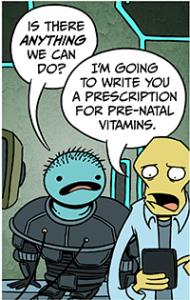

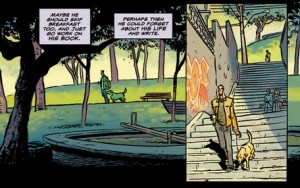

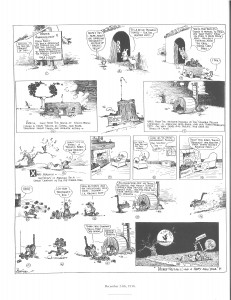

The final page of the 1955 EC Comics adaptation of “I, Robot.”

Those two panels in the center of the page pose an interesting challenge for the reader: first, Orlando and colorist Marie Severin ask us to identify with Adam Link, whose long, cylindrical forehead and mechanical jaw cast distorted shadows on the yellow wall behind him. He is, for a moment, almost human, as he makes a plea not to be turned into a monster by humanity’s hatred and violence. The text that appears over the panel, however, tells us, “I hear you now, shouting outside…” While we might sympathize with the protagonist, especially after the loss of his dog Terry on the previous page (in the original story, as the mob fires on Adam, a stray bullet kills the dog), we also, for a moment, inhabit the role of the aggressor.

The next panel is even more fascinating. We share Adam Link’s point-of-view as we stare out a window at the men, most of them carrying a rifle or a torch or both. Just two panels earlier, we saw Adam Link before that same window, reading his creator’s copy of Frankenstein. Now, however, the scene has changed, and we stare with horror at the grotesque figures that approach Dr. Link’s laboratory. Again, the text box disrupts our sense of identification with the robot: he addresses us directly. We are part of the mob. As we stare out the window, we are looking not at a display of “hatred lust” and impending “death” but at ourselves, and our petty hatreds and small-minded prejudices.

“I, Robot” inverts Qiana’s original question and seems to ask, Can this EC comic transform you, the reader, into a lustful, bloodthirsty, bigoted villain? Or have Otto Binder and Joe Orlando merely held a mirror up to EC’s audience, one they hope will challenge readers to reflect more deeply on issues beyond the fantastic realm of the comic itself?

Binder addresses these issues in another EC adaptation of one of his earlier science fiction stories, “The Teacher from Mars,” also drawn by Joe Orlando and colored by Marie Severin for Weird Science-Fantasy Number 24 (dated June 1954). As Schelly points out in Words of Wonder, Binder selected “The Teacher from Mars,” first published in Thrilling Wonder Stories in 1941, for Leo Margulies and Oscar J. Friend’s 1949 collection My Best Science Fiction Story, which includes stories from Isaac Asimov, Robert Bloch, and Harry Kuttner. In his introduction, Binder explains that “the story,” in which human students abuse and terrorize their Martian teacher, “was a good medium for showing the evils of discrimination and intolerance. Sadly enough,” he continues,

we have not yet eliminated those degrading influences on our world. The Martian in this story is the symbol of all such reasonless antagonism between “races.” Not that I wrote the story solely for that reason. It just happened to strike me as the best “human interest” approach. The “moral” was incidental.

In most of his work, from the Captain Marvel stories of the 1940s through his Superman narratives in the 1950s and even his scripts for Gold Key’s Mighty Samson in the 1960s, Binder again and again sought to explore what he refers to as the “‘human interest’ approach.” As Bill Schelly has argued in his comments on “The Teacher from Mars,” “Though Binder denied that the anti-discrimination sentiments in the story were his main reason for writing it, they are there nonetheless.” Therefore, is the “moral” really “incidental” in “I, Robot” or “The Teacher from Mars”? And what does Joe Orlando’s work bring to these comic book versions of Binder’s original short stories?

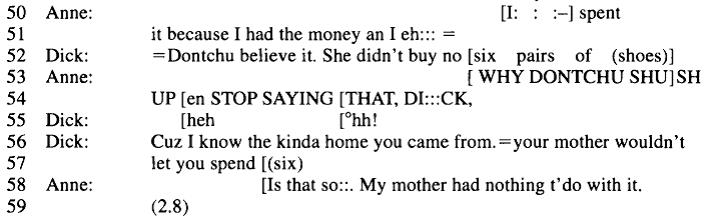

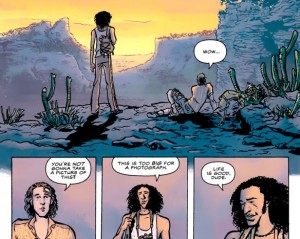

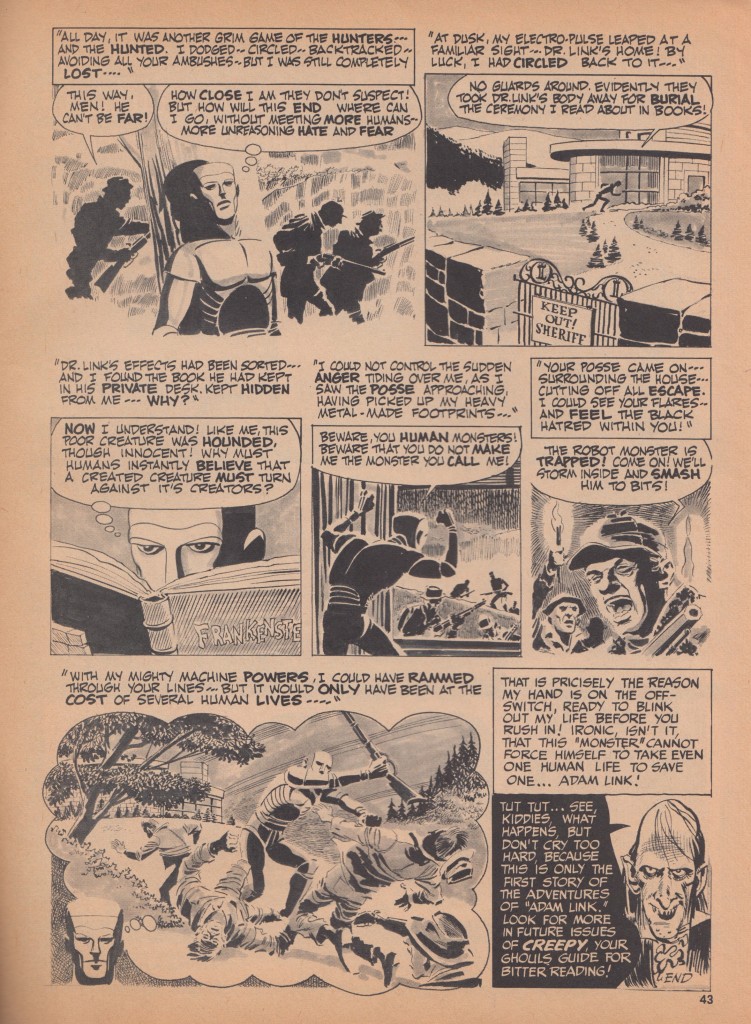

The final page of Binder and Orlando’s adaptation of “I, Robot” for Warren Publishing’s Creepy

No. 2, 1965 (page 43).

The EC version of “I, Robot” raises interesting questions, not only about adaptions of prose works into comic book form, but also about the moral imagination of creators like Binder and artist Joe Orlando. The complexity of the point-of-view in Adam Link’s narrative might be read in light of a passage from James Baldwin’s essay “Everybody’s Protest Novel”:

The failure of the protest novel lies in its rejection of life, the human being, the denial of his beauty, dread, power, in its insistence that it is his categorization alone which is real and which cannot be transcended.

How might Baldwin’s critique of Uncle Tom’s Cabin and the “protest novel”—a work of fiction that sets out to raise consciousness and fight social injustices—help us to read the many versions of Binder’s “I, Robot”?

One possible answer is this: because the story of Adam Link is a very obvious fiction, one built, as Binder himself admitted in the January 1939 issue of Amazing Stories, on Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, it makes clear its status as a work of the imagination—that is, as a text (you can read more of Binder’s introduction to the original “I, Robot” in Schelly’s biography). “I, Robot” makes no claims to realism or verisimilitude. It might be read simply as an engaging adventure, or as a moral lesson on our jealousy, hatred, and ignorance. But we might also place the multiple versions of Binder’s story in dialogue with each other as well as with other texts from the era in which they first appeared. The January, 1939 issue of Amazing Stories, for example, appeared just a few months before the first publication of James Thurber’s “The Secret Life of Walter Mitty,” another relic of the period that continues to fascinate American audiences in the form of Ben Stiller’s new film. As we explore the shape and the dimension of the society in which Binder lived, we have an opportunity to investigate how his America shaped our own. And as we read this comic book from 1955, Adam Link continues to address us, even now, as, in the closing lines, he remarks, “Ironic, isn’t it, that I have the very feelings you are so sure I lack?”

Last week, after we saw Her at the Landmark on the corner of Clark and Diversey in Otto Binder’s old hometown of Chicago, I wondered, What would Binder have thought of this 21st-century story of the love between a middle-aged man and his operating system? And what does Binder’s “I, Robot” in all its forms—from the original story to the later EC Comics and Creepy versions to the novel Adam Link—Robot Binder published in 1965—ask of us as modern readers and as comics scholars?

References and Further Reading

Baldwin, James. “Everybody’s Protest Novel” in Notes of a Native Son. Boston: Beacon Press, 1984.

Binder, Eando. Adam Link—Robot. New York: Paperback Library, Inc. 1965.

Binder, Otto. Letter to Sam Moskowitz. October 4, 1952. Courtesy of the Otto Binder Collection, Cushing Library, Texas A&M University.

Binder, Otto. “The Teacher from Mars” in Leo Margulies and Oscar J. Friend, My Best Science Fiction Story. New York: Pocket Books, 1954. 18-36.

Schelly, Bill. Words of Wonder: The Life and Times of Otto Binder. Seattle: Hamster Press, 2003.

You can also read Noah’s discussion of Her and its relationship to Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? at Salon. Qiana’s paper at the 2013 Dartmouth College Illustration, Comics, and Animation Conference, “Science Fictions of Race in EC’s ‘Judgment Day,’” was another inspiration for this post.