The previous contributions to our roundtable have raised important questions about Thierry Groensteen’s approach to page layout in Comics and Narration. While a rich array of images in Adrielle Mitchell’s post encouraged us to consider how frame irregularities produce meaning, Roy Cook set the stage for an important conversation about the values comics readers attribute to different panel arrangements. Roy’s post really got me thinking about the way Groensteen privileges the layout pattern of the “waffle-iron” by identifying stability, simplicity, and transparency as fundamental attributes of the orthogonal shapes. Groensteen further conceptualizes the grid in the narrative rhythm of comics as the “basic beat” against which the visual and verbal elements of comics can improvise.

From this perspective, it’s not difficult to see how one might characterize the grid as “regular” or “neutral” or “invisible,” but I remain troubled by the relative nature of these terms, who defines them and in what context. To complicate the issue, my first instinct was to seek out comics that delight in the wildly experimental layouts that Groensteen might find “more sophisticated (or more hysterical),” but Adrielle’s post provides several excellent examples already. So I thought I would ask instead about comics that use the grid, but in unexpected ways: how do comics adapt the basic panel layout in order to stray from what Roy described as Groensteen’s “waffle-iron way of truth”? When is a grid not just a grid?

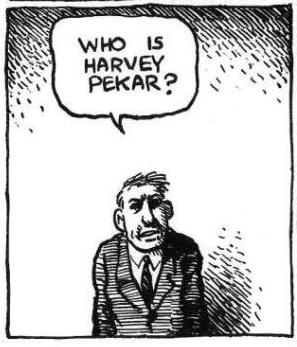

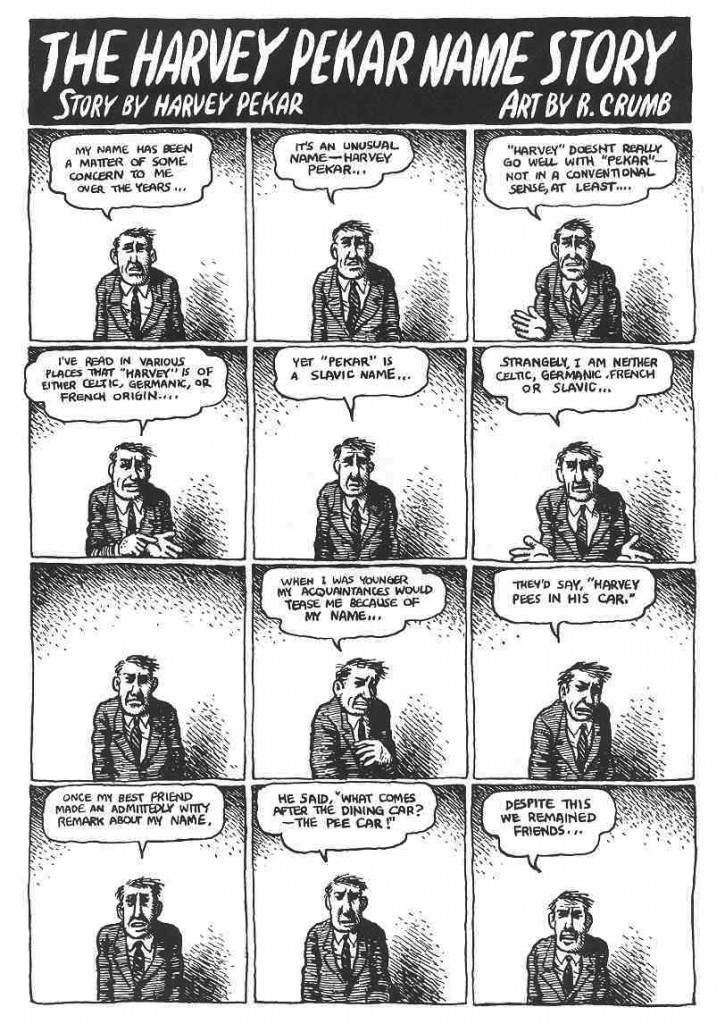

I wonder, for example, how a comic like “The Harvey Pekar Name Story” fits into our understanding of frame regularity and rhythm. Though we may be inclined to make assumptions about its uniformity at first glance, R. Crumb has not simply drawn 48 identical copies of the same man in the squares of this four-page comic about the different Harvey Pekars listed in the phonebook.

The text varies and so too do the hand-drawn panels that reveal each frame’s scratchy imperfections. The careful reader’s eye becomes attune to the nuances of Harvey’s expression and posture. It is a “basic layout pattern” and yet it has “irregularity as a common feature” (43) — a fitting contradiction for a story about Harvey Pekar’s search for his own unique identity. It seems to me that a comic like this one actually exposes the illusion of neutrality by calling attention to the grid’s own constructedness.

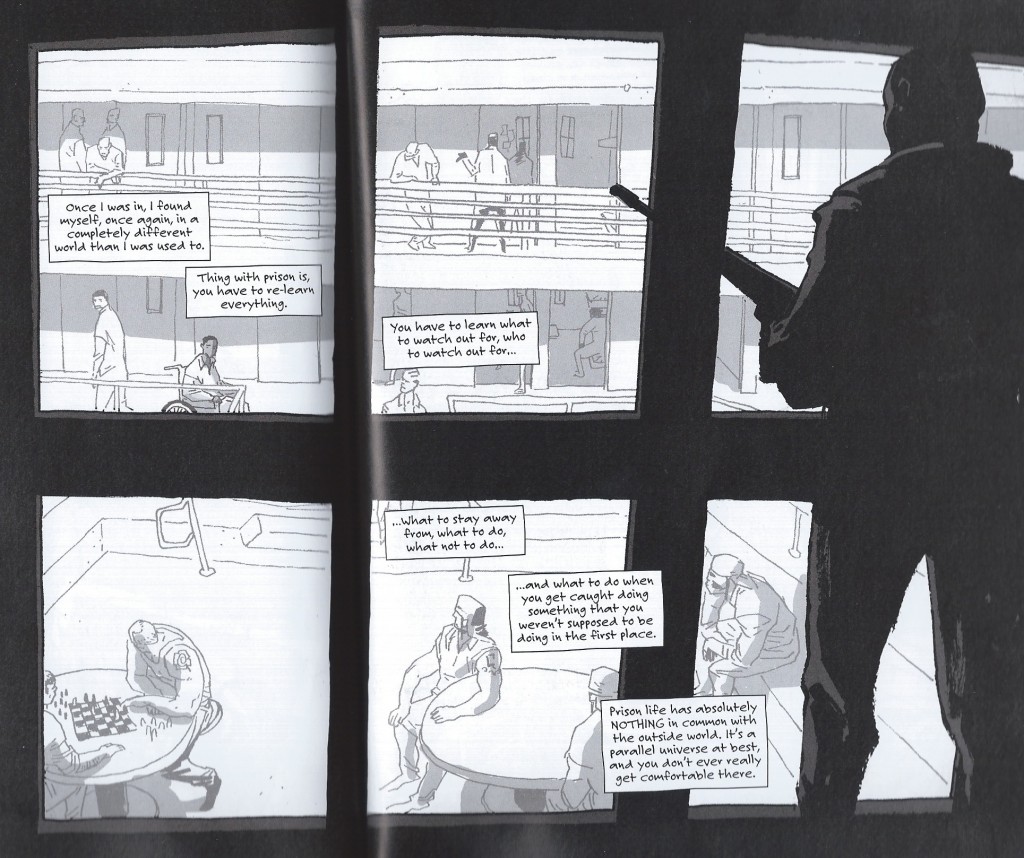

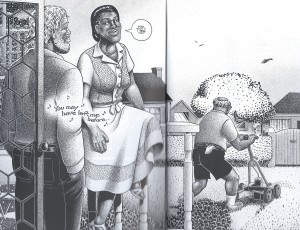

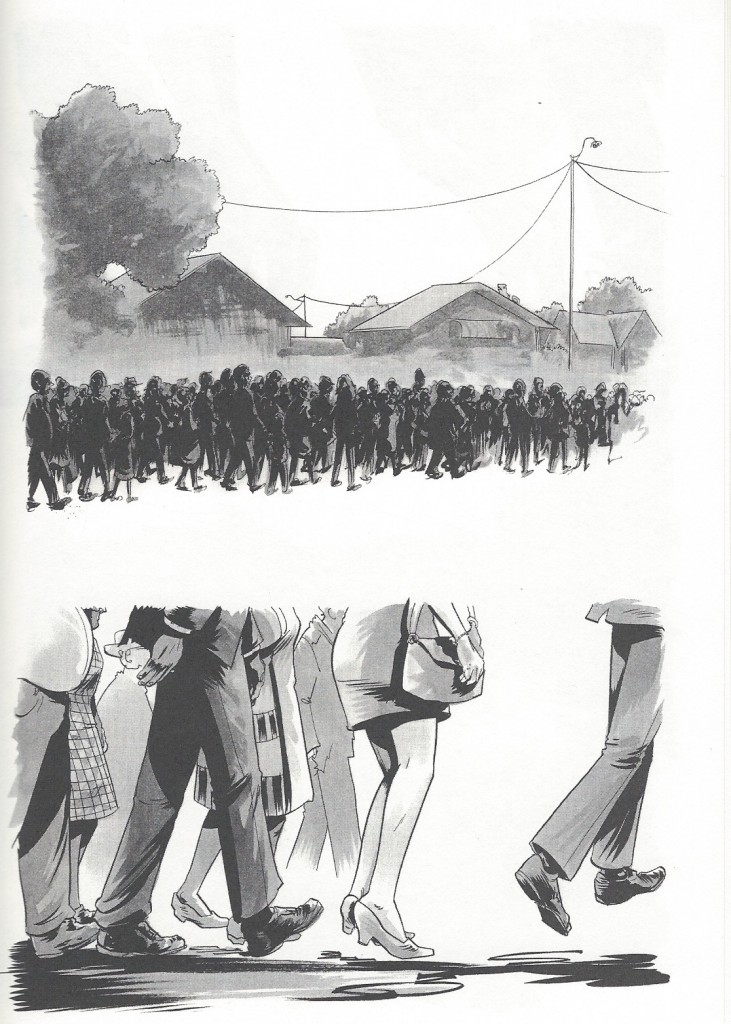

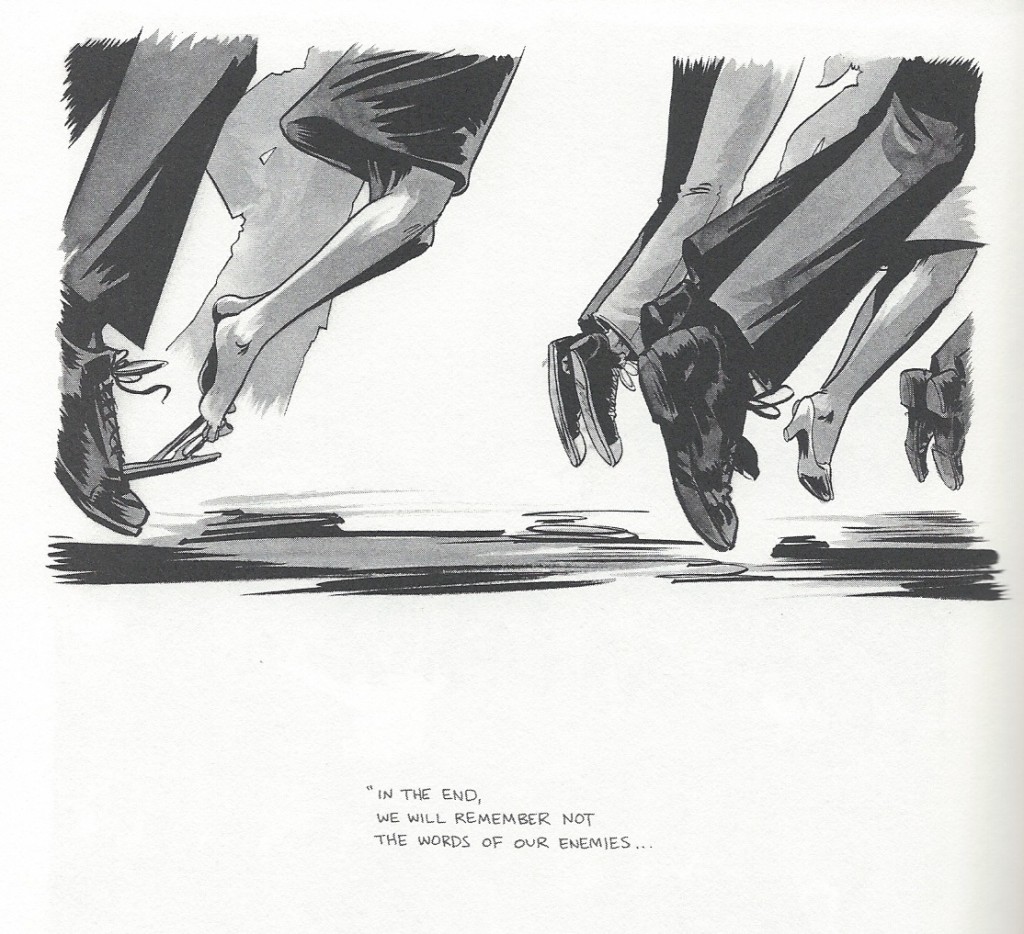

Another example that comes to mind for me is a two-page spread from Percy Carey’s graphic novel memoir Sentences: The Life of M.F. Grimm with art by Ron Wimberly. During Carey’s time in prison on a drug conviction, Wimberly uses the bars of the jail cell to structure the layout of the page, building barriers between us and the detained bodies, the narrative boxes, and the armed guards

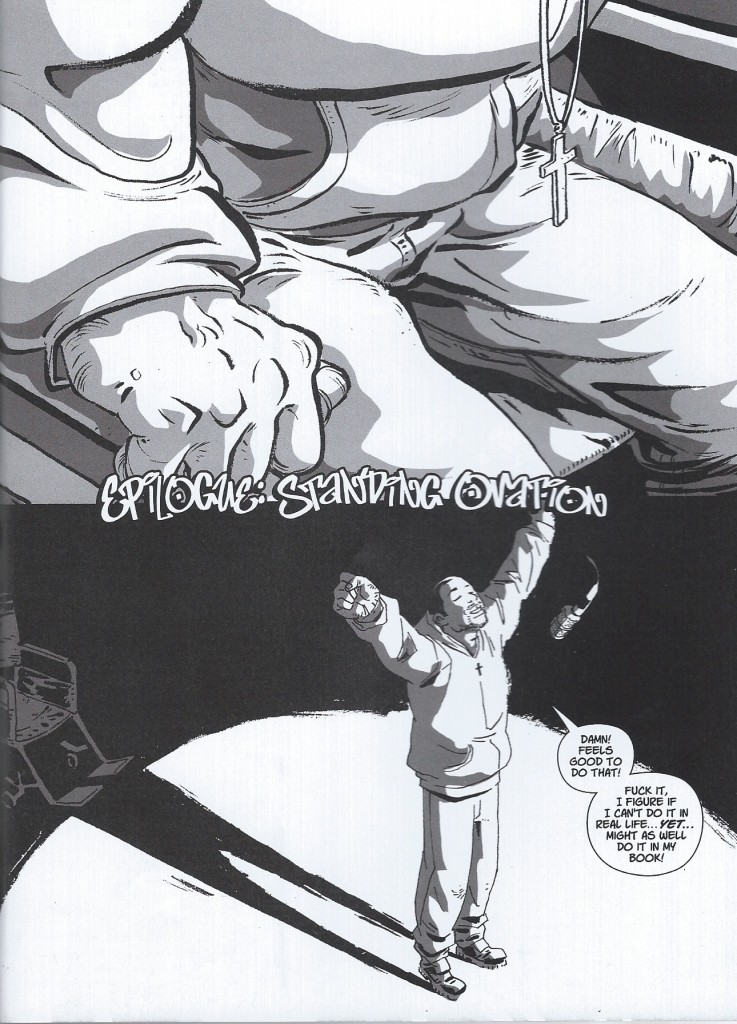

Groensteen describes the thick borders that Chris Ware uses in Jimmy Corrigan as having “an almost carceral appearance” (48) and given the emotional constrictions of multiple generations of the Corrigan family, Ware’s panel choices aid in the production of that meaning. Alternatively, Sentences is a comic that has an unpredictably fluid design with layered panels and splash pages to convey the early days of hip-hop and Carey’s experience with music, drugs, and violence during the 1990s. The waffle-iron pattern is not the norm by any means; when the grid above appears, it actually disrupts a narrative rhythm that the writer and artist have already established. The uniformity of the panels might also be said to reflect the carceral lens that would continue to follow Carey after being released from prison.

Is this frame neutral or invisible? How might the perspectives of these two comics help us to reconsider the notion of the “basic panel layout” in other comics?