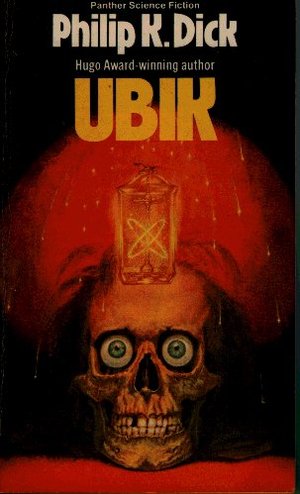

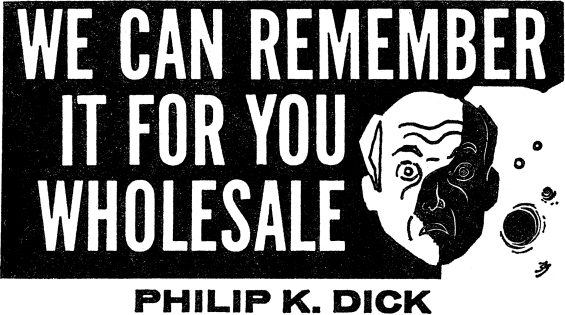

We had a little chatter about Philip K. Dick a couple weeks ago in comments, so I thought I’d reprint this tribute. It originally ran on Poor Mojo’s Almanac.

_____________________

I.

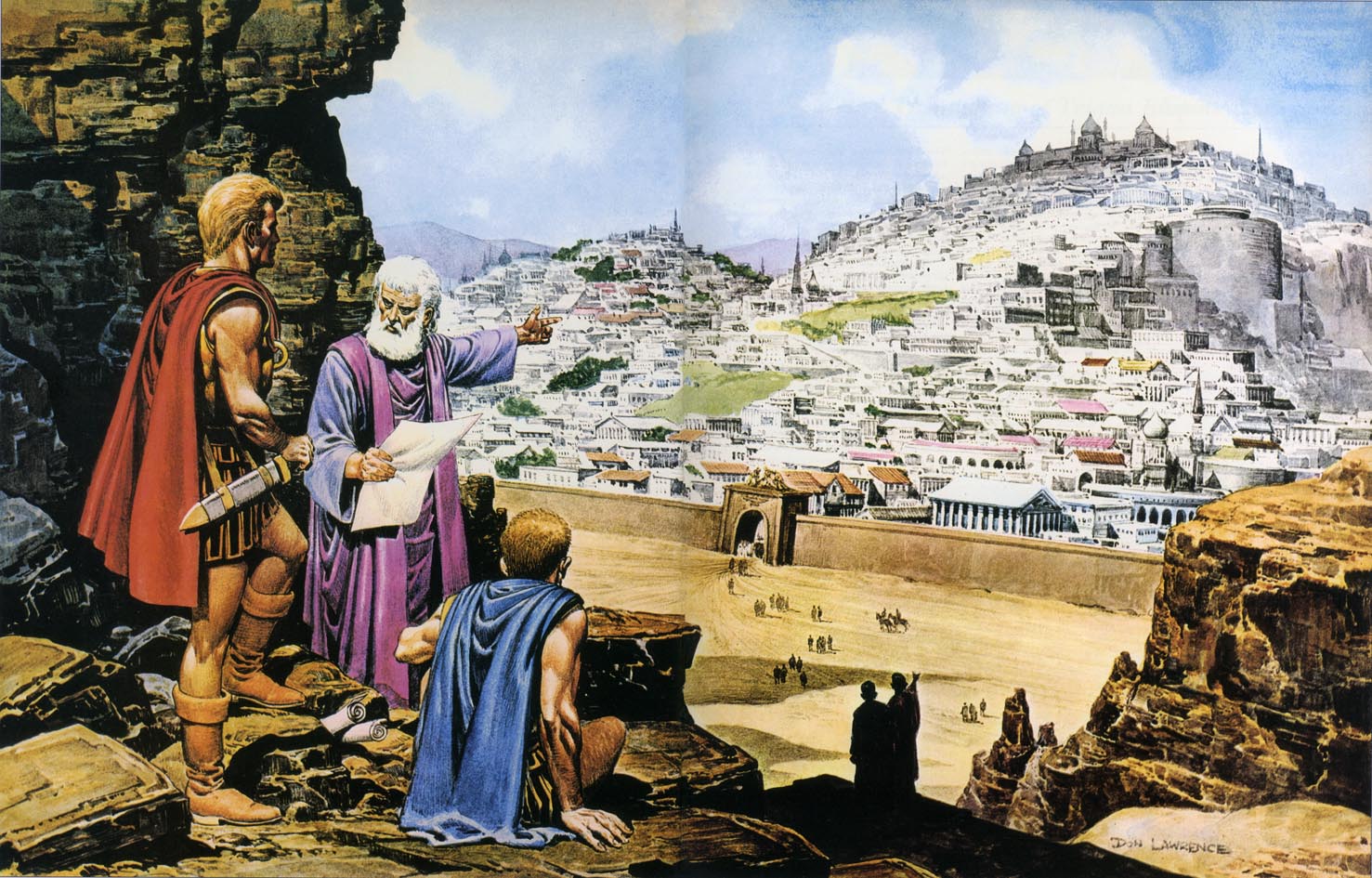

“France is the name of our starship,” Maximilien Robespierre tells Danton, “and France is the name of the planet from which we come. But the true France is our destination, the land of equality and virtue to which mankind has always been rising, which you and I shall finally attain!”

Robespierre straps on his blaster and inspects the ship. He checks each porthole for cracks, examines each control panel for tampering. He discovers seven men smuggling Thermidorian Brainburning Petals, sets his weapon to “Guillotine”, and executes them on the spot. He calls his crew together and paces in front of them. “Citizens,” he cries, “it has come to my attention that giant green alien psychic royalists are seeking to invade our democratic ship! Even now their agents may be teleporting on board; even now they may be among us, attempting to introduce their evil morale weakening substances into our untainted bloodstreams! We must be strong, we must be vigilant, we must shoot to kill anything we see that is green or giant or that demonstrates unnatural mental powers!

A ragged cheer rises from those assembled; the men raise their blasters, the women toss flowers. Already, though, Robespierre can see that several of the citizens are tinged with green; even some of the children appear to be larger than any three normal men. After he dismisses the assembly, Robespierre commands the ship’s computer to play patriotic songs, but still he feels weak and sad as he stands alone with Danton on the bridge. “It is hard,” he says, “this voyage, without knowing how long we must travel or exactly where we are going.”

“Yes it is,” Danton agrees. Robespierre notes that the other man does not move his lips when he speaks; as he watches, in fact, Danton grows enormous, his face becoming a vast expanse of green.

Robespierre retreats to his own quarters. He sits down at his plain desk and listens with eyes closed as the Muzak version of the “Marseillaise” drones from his nondescript terminal. “Computer,” he says. “What percent of the crew aboard this ship are aliens?”

“One hundred percent,” the computer says.

Robespierre nods. When he opens his eyes, he sees that his desk is covered with purple Thermidorian Bulbs.

“Computer,” he says again, keeping his voice steady. “Does that include me?”

“You are an alien,” the computer says.

Robespierre feels tears on his cheeks. All our efforts, he thinks. All the lives lost for nothing. We will not create a new age of reason, we will not free ourselves from tyranny. We will never reach France.

“Yes,” says the computer, although Robespierre did not speak aloud. “We are already heading back. We are returning to France.”

II.

Salesperson Immanuel Kant pitches over the counter medication on prime-time holovid. “Feeling down?” he asks, grinning furiously into the camera even as he pops a small white capsule into his mouth. “Are you depressed, dreary, anxious? Luckily for you, there’s a product that can help. After years of measuring, quantifying, parceling, and splicing, our scientists have finally discovered the formula for God. Caught in the middle of a nuclear holocaust, an alien invasion, a meteor shower, a messy divorce? Then try Numenol, the amazing drug that can make you divine! That’s Numenol — for fast, fast transcendence! Available in tablet or capsule.”

Unemployed Aerocar Repairman Immanuel Kant sits in his run-down apartment in the sky-bubble city of Konigsberg on the planet Jupiter and watches the salesperson on the holovid. “That’s what I need!” he thinks to himself. “Instant revelation — a way out of this mess of my life! ” He half turns on the couch to address his wife in the kitchen. “Say, honey,” he calls. “Have you heard of this new drug, Numenol ? I think I’m going to run down to the drugstore and pick some up!”

His wife, Supermarket Cashier Immanuel Kant, comes out of the kitchen. He smooths his dress. “Actually,” he says, “I bought some just the other day. The effects are very strange. Not at all as advertised.” He glances contemplatively out of the window. On the street below, underneath the towering atmosphere dome Immanuel Kant walks arm in arm with Immanuel Kant as Immanuel Kant navigates his aerocar amidst the skyscrapers in which Immanuel Kant attends meetings directed by Immanuel Kant concerning the new plans for a hundred Immanuel Kants to colonize yet another planet far off among the stars.

Night falls on Konigsberg and Immanuel Kant stands outside a holovid store. Behind the glass, five rows of 3-d images of Immanuel Kant jabber incessantly into the darkness. Immanuel Kant spits on the sidewalk in disgust. “A fine job you’ve done,” he says angrily. “I could have spent the rest of my days quietly enough here. I had problems, sure, but they weren’t insoluble. And now look at me! I’ve murdered a man on Venus and been raped in the Alpha Centuri system, down the block my wife hates me and on the other side of this world I’ve contracted a horrible disease that’s making my face melt. I have lice and a headache and a cold and I can’t find work or food or cash to pay the rent. I trusted you to make me God, and instead you’ve just made me more confused and miserable than I ever was before!”

The hologram Immanuel Kants each raise an admonishing index finger. “Now Immanuel,” they say. “We understand that things seem hopeless at the moment and that you feel like you’re no further along than you ever were. But we’d like to remind you that these things take time. We’ve gotten omnipresence now, so surely omnipotence and omniscience and eternal youth etc., won’t take us much longer. You’ve just got to have a little faith, keep smiling, and we assure you that you won’t be disappointed. Trust me. You have your own word on it.”

Kant turns from the screens, his fists clenched. But what can I do? he thinks. He looks up at the stars, shining high above the sleeping city, even as, in a spaceship somewhere far above the dome, he looks down upon Jupiter, upon himself. His hands relax, he draws a deep breath. Behind him, Immanuel Kant on the screens watches Immanuel Kant with shoulders slumped walk alone into the darkened town.

III.

Saint Bernadette looks out the window of her parents cubicle on Venus and sees a girl no larger than herself standing without any breathing equipment on the surface of the planet. She puts on her own respirator and goes outside.

“Why can you breath out here?” Bernadette asks.

“Que soy era Immaculado Conceptiou,” says the girl. “I am the Immaculate Conception, Mother of God.”

The Virgin Mary becomes an instant celebrity. She appears on talk shows and launches her own satellite to relay pre-taped advice round the clock. She personally visits as many family cubicles as she can. “I have been sent by Earthgov to let you all know the colonies have not been forgotten,” she says. “There is still a place for your souls on earth after death.” Everywhere the colonists are happier. Bernadette’s own parents begin to smile on occasion, where before they had been always silent and grim.

When Bernadette turns twenty, two policemen come to take her to a detention camp. “You are sick,” the first one explains. He is huge; his purple uniform stretches before her like a wall. “We’re very sorry to have to do this to a saint,” the second one says, gently taking her wrist. His eyes are blue and sad. “But you have asthma — we can’t allow such deviations. Our population must be pure if we want to continue to survive.”

“Mary could cure me,” Bernadette says.

“The policemen exchange glances. “Perhaps,” says the one with blue eyes.

At the camp Bernadette lives in a room with many other men and women. Some of them are lame, some are blind, some can’t hear. Every day they all go to the surface to farm the Venusian dust. Bernadette’s asthma grows much worse.

One night she wakes up and finds the blue-eyed policeman leaning over her. His flashlight casts eerie shadows on his face. “Are you awake?” he asks.

She nods, feels a shiver of fear. “Yes,” she says.

“Listen,” he says. He focuses on a spot to the left of her head. She notices that he is not wearing his hat — his hair is pale in the dim light. “Listen, I can see that you’re a loving type of person. I think that’s why you’re sick. I don’t think you have asthma at all. It’s psychosomatic, a symptom — it’s a kind of cry for affection. This world, Venus, it pulls us apart from each other.” He reaches out awkwardly, takes her hand in his own. “I want to help you,” he says, “If you’ll love me….”

Bernadette looks in disbelief at her own hand in the policeman’s grip. He thinks I’m going to get better because he says so, she thinks distantly. He’s as sick as me, sicker. He has no grip on reality at all.

“Leave me alone,” she says aloud. Her breath whistles as she inhales. There is a shallowness in her chest.

The policeman lets go of her hand. He takes a step back and shines the light at her face, so she can’t see him at all. “All right,” he says. His voice is ugly with anger. “If that’s the way you want it. I know your game. You’re too good for me, right? You want to be sick so your precious Virgin can come and heal you. Well, let me tell you something. The Virgin, she doesn’t exist, see? She’s an android. And Earthgov didn’t even send it, either, because Earth’s been a dead planet for years now — they blew themselves up long ago. It was Venusgov that built Mary, to raise morale among the stupid farmer underlings like you. So how do you like that? You just gave up your chance to live for the sake of a machine.”

Bernadette lies alone in the dark as the policeman stamps down the long hallway to the door, slams it behind him. She wonders if anyone else in the whole room is awake. She can’t hear over the sounds of her own gasping breaths. She sucks air into her lungs as hard as she can, but she can’t get enough. That man’s killed me, she realizes. I don’t even want to live now. She tries to convince herself that he was lying, but she can’t do it. He had seemed so confident and she has no energy. Everything is taken up by the need for the next breath, and the next. The Virgin a robot, she thinks. But she wasn’t lying. Made without intercourse. Soldered and hammered, rather. Immaculate Conception.

The room fades, disappearing into black as Bernadette’s strength ebbs. Then there is blinding light. Mary bends down, takes Bernadette in strong metal arms.

“Will you heal me?” Bernadette asks. “Will you take me to Earth?”

“All are healed,” Mary says. “All are taken to Earth.” Around the room, from every bed, the crippled rise dancing on metal limbs, the blind open photoelectric eyes, the mute begin to sing from stereo voice boxes. Mary’s face is a painted mask of tenderness as Bernadette inhales with plastic lungs the poisoned air of Earth.

IV.

Philip K. Dick leaps from his chair, suddenly awake. “I had a dream!” he exclaims. “A dream that all of history had turned into my novels, that I was writing the script of reality!” He blinks twice rapidly, scratches his beard and looks around the room. The party has ground to a tired end; no one is listening to him. Maximilien Robespierre lies unconscious on the couch. Saint Bernadette sits on the bare wood floor, sucking on an unlit hash pipe and staring wide-eyed at the toe of her shoe. Immanuel Kant leans on a broken lamp, wearing underwear, socks, and an expression of dazed befuddlement.

Phil isn’t discouraged. He raises his voice, waves his arms, downs a fistful of amphetamines. “So what that means,” he shouts, “is that when I die is the Apocalypse, when I stop writing for a moment everything stops! We’re not even here right now since I’m not at the typewriter!”

Kant lets go of the lamp, crosses his arms on his chest, shouts something inarticulate and falls to the floor with a crash. Friedan has woken up and is making a vague effort to roll Robespierre off the couch. Bernadette begins coughing violently.

Phil bites his lip. He looks from Kant to Bernadette to Robespierre to Friedan. “Don’t go anywhere,” he says. “I have to get going…got work to do, got to bring you all into being!” But he doesn’t leave. Instead he takes two hesitant steps forward and squats down beside Bernadette. She is still coughing. “Stop that,” he pleads. Instead she coughs harder, bending so far forward that her face almost touches the ground. The hash pipe falls from her fingers and the burnt ashes jump from the bowl, scatter across the floor. Phil stares at them helplessly. They look like a burning spaceship, a metal hand, a frightening alien face. Still he keeps looking, desperately hoping to find some pattern beyond indifference and pain, some way to create the world.