Comics Versus Art

by Bart Beaty

University of Toronto Press, Scholarly Publishing Division, 2012

Its tempting to split up a review of Beaty’s book, Comics Versus Art, into a series of examinations of its individual chapters. Many of Beaty’s arguments are so relevant to the discussion of comics and wider culture that they deserve their own posts. More devilishly, its equally seductive to make a laundry list of his most controversial claims, just to see if they could nudge the Lichtenstein conversation out of its current emotional stalemate.

Either approach would be easier to write than an evaluation of the whole: Comics Versus Art is an ambitious but uneven chronicling of the diverse historical frictions between the two fields, including but not limited to pop-art appropriation, comic’s belittlement as nostalgic/primitive ephemera, and cartoonists’ ready cooperation with ‘art world’ prejudices. Beaty is a firebrand and much-needed documentarian, and his book is an invaluable contribution to this discussion. Through an interweaving of many rewarding tangents, he often succeeds at elucidating, even correcting, accounts of art-comics friction through a fair examination of each case’s larger context, even if some of his dramatic conclusions are shakily reached or unearned. Comics Versus Art is far from a manifesto of why comics should or should not be art. Without being vehement or trite, the book is quite damning in its examination of the petty status games that occur at the border between these worlds.

Comics Versus Art is comprised of nine different “case-studies.” The first chapter is especially worth summarizing, as it examines several different definitions of comics, and how these definitions, particularly Scott McCloud’s, have exempted comics from art history. While most definitions of comics have been essentialist, (focusing on recurring characters, thought balloons, or moral narrativising as central components, depending on the theory,) McCloud’s formalist definition is open enough to abduct and rename other phenomenon as “comics,” while it rejects several examples widely accepted as comics, (Dennis the Menace, for example.) While McCloud’s proponents are happy to re-envision Trajan’s Column as a comic, (and couldn’t care less about Dennis the Menace, perhaps,) the rest of the art world remains indifferent; as a freak, isolated case of comics, the column’s new branding doesn’t have nearly the historical interest as it’s status as imperial propaganda. More importantly, ‘comics,’ ‘children’s books,’ and ‘artists’ books’ are only distinguished by their audiences. At this point, Beaty introduces an institutional definition of comics, borrowed from Arthur C. Danto, George Dickie and Howard Becker’s theories of an “artworld.” Loosely, comics are whatever the human members of the comics world (including but not limited to producers, critics and consumers,) deem to be called comics. This theory fails even more spectacularly in establishing borders with children’s and artist’s books, but that’s somewhat the point, and at least it’s honest about it: Becker writes that “‘art worlds typically have intimate and extensive relations with the worlds from which they try to distinguish themselves.’” Problematically, this theory has no way of pinpointing why or what about comics makes them a social nexus, (perhaps, by the centrality of recurring characters in comics, people really do gather around commercial franchises rather than their formal attributes.) Beaty does good work here in positing a parallel comicsworld, but the definition is tautological and directionless, and doesn’t quite address where this would overlap with an artworld anyhow. Moreover, Beaty doesn’t develop the comicsworld theory beyond this point, and only occasionally reintroduces it in further chapters. He also doesn’t cover any of the historical evolutions in the definition of ‘art,’ contextualize how Danto and co.’s definition interact with these, or how it can be expanded past a truism. This unbalance plagues most of the book, where Beaty uses a limited range of analytical approaches to draw his conclusions, and doesn’t apply these tools strictly enough to spawn ideas past his original biases.

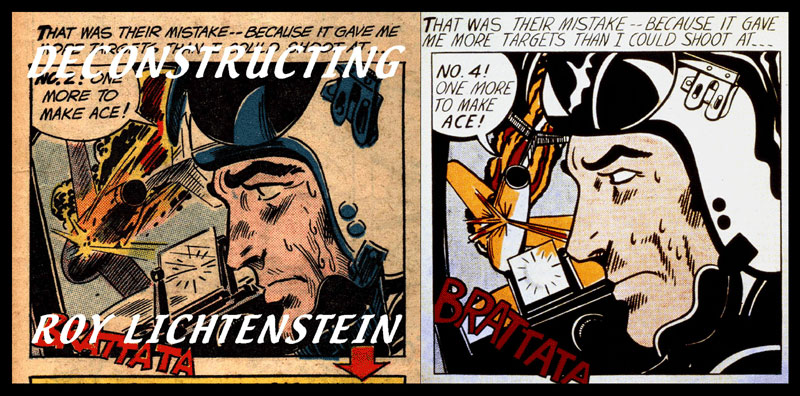

Beaty misses the opportunity to develop the institutional theory with the next chapter, which details the gendered power dynamic underlying the Lichtenstein appropriation debate. This study could have benefited from a closer look at the sub-worlds at play: much of the art-world initially rejected pop-art for its association with low-brow cultural forms, and only gradually began to recognize Lichtenstein’s work as worthwhile. This in turn would have clarified Chapter 6, where Beaty erroneously concludes that Gary Panter’s featuring in Blab! and Juxtapoz magazines, and creation of a vinyl art toy, signals his acceptance by the art world at large. Panter’s luke-warm reviews by Artforum, one of which is included in the book, are slightly better than the New York Time’s treatment of another comics luminary decades earlier, Bernard Krigstein, who is instead framed by the book as an artworld failure.

Despite this, Beaty’s arguments have an commonsensical ring of truth, which he occasionally goes out of his way to justify. On Lichtenstein, Beaty frames the case study with discussion of Nietzschean ressentiment, defined as “a tendency to attribute one’s personal failures to external forces.” This is a little overkill, where simply using the word ‘resentment’ could have done the trick, as Nietzche’s philosophies are not mentioned elsewhere in the book. However, Beaty is on the right track:

When, for example, Clive Phillpot offhandedly dismisses the possibility that works of comics might be classified as artist’s books, the division between forms is presented as a self-evident commonplace barely requiring elaboration or argumentation. By contrast, the pent-up aggressive feelings towards the world of fine arts that characterizes many cartoonist’s ressentiment can become an all-consuming passion that threatens to poison their work with an easily diagnosed bitterness.

It is a breath of fresh air to have the emotional dynamic of the Lichtenstein debate not only included in its context, but considered the heart of the conflict itself. In this case, he also studies how, evidenced by critics of the time, comics and kitsch were increasingly cast as feminine, while pop-art’s appropriations ‘masculinized’ camp that had been enjoyed in earnest. “Pop art, therefore, was a threat because it absconded with the one element that comic book fans assumed would never be in question: the red-blooded American masculinity that informed war and romance comics alike with their rigid adherence to patriarchal gender norms.” It is gender critique, not institutional theory, that becomes the lifeblood of Comics Versus Art, and provides a continuing thread through the other case studies, something that will fly in the face of readers not prepared to understand how certain behaviors and attitudes are routinely cast as ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’ throughout history. Beaty writes,

The validation of the comics form, which is an essential aspect of fannish epistemology, can take many paths. One of these paths would be the outright rejection of the conservative basis of much of modernist art history, with its conflation of masculinity, artistry, and genius, and the adoption and promotion of new aesthetic standards that would recognize the importance and vitality of feminized mass cultural forms. Another, far less revolutionary, route would be a capitulation to the dictates of modernist art history and the nomination of a select few cultural workers to the position of Artist or Author. In the wake of pop art, it was this latter approach that was most commonly, and effectively, utilized by comics fandom, as they worked to export the idea of the comics artist beyond the limitations of the comics world.

Beaty extends this to comics content, where the industry tends to reward subject matter that reinforces gender tropes, either those of hyper-masculine heroism, or the imagination of the isolated, tragic genius, what critic Nina Baym calls “a romanticization of the straight, white male subject as the object of societal scorn.” The most successful cartoonists play into the art-world’s existing stereotyping of cartoonists, and behaving like primitive, ( R. Crumb,) or pathetic, (Chris Ware,) versions of the Romanticized genius. Ware is treated as a synecdoche for the current status of contemporary comics, where his savvy use of draftsmanship, nostalgia, self deprecation, and an attitude that is “willfully ironic about the relationship between comics and art in a way that serves to mockingly reinforce, rather than challenge, existing power inequities,” make him the kind of artist that “if Chris Ware did not exist, the art world would have had to invent him.”

Comics emerges less as a victim of art than of its own, unintentional self-sabotaging, and its refusal to grow and celebrate itself on its own terms. Mainstream and alternative comics’ insecurities over their belittlement (better, feminization,) by both Romantic/conservative and contemporary art frameworks cause them to miserably ape ‘high art’ conventions, establishing canons and idolizing masculinized genius-creators. Even when the artist doesn’t paint himself according to the genius archetype, (Charles Schultz’s optimism and transparent mercantilism, for instance,) he can usually be reconstructed to fit it– while those outside the comics world tend to recognize Peanuts as a sweet, nostalgic, family franchise, fan-critics instead emphasize a tragic and masculinized reading. One great example lies in comparing Fantagraphic’s conneuseurist The Complete Peanuts, with their unsettling, somber jackets, to the fabulously popular Peanuts paperbacks from decades before, such as Happiness is a Warm Puppy.

While not revolutionary, Comics Versus Art’s greatest service is to document these dynamics, attitudes and interactions between comics and art, so that they can be read against each other, and found in one place. It’s greatest crimes are its most obvious omissions–like the development and role of comics museums, conventions and festivals, and the erasure of the Terry Zwigoff’s Crumb, (now included in the Criterion Collection,) in the biography of the artist. Most unforgivably, Beaty omits the history of ‘deskilling’ in the art world, how deskilling inspired the institutional theory Beaty employs, and how it is an unmissable component of the artworld and the comicsworlds’ mutual dismissals of each other. Compared to that, his zany, unsupported claim that McCloud has distanced the comics and art worlds, rather than bring them closer together, is amusing, and his haphazard braiding of information, where certain lines are suddenly dropped, only to be weaved back in, only mildly frustrating. Comics Versus Art was a gargantuan project for one scholar to undertake, its faults are expected along those lines, and the book is self-consciously a testament to the fact that there are too few critics working on such a crucial, cultural history. In any case, Comics Versus Art is a great groundwork for future discussion, and a fiery read.