This being the last of our five-part roundtable on George Herriman’s seminal comic strip and coincidentally the last post before Christmas, I thought it might be fun to reflect on two Christmas episodes from Krazy Kat.

As consumers of pop culture, the holidays are a time for us to engage in uncritical enjoyment of TV Christmas specials. There’s something comforting about knowing that the fictional worlds of the shows we follow align with our own seasonal cycles. What’s more, television producers know that Christmas specials have to deliver more and newer viewing pleasures than the usual, so they tend to be worth watching. Christmas specials are always highly conscious of past Christmas specials, and even conscious of past Christmas specials from other shows, so they become uniquely citational, genre bending, and just generally “meta.” I’d like to think that Christmas specials are capable of “inoculating” their viewers against the undifferentiated time of those late-capitalist spaces associated with Christmas, such as big box stores and malls, by placing them into a more telluric time, even if through fiction. The same can be said of comic strips, which are published year-round, for typically longer runs, and which align perhaps even more neatly with the seasonal timeframe of their readerships than does TV.

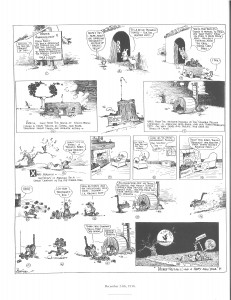

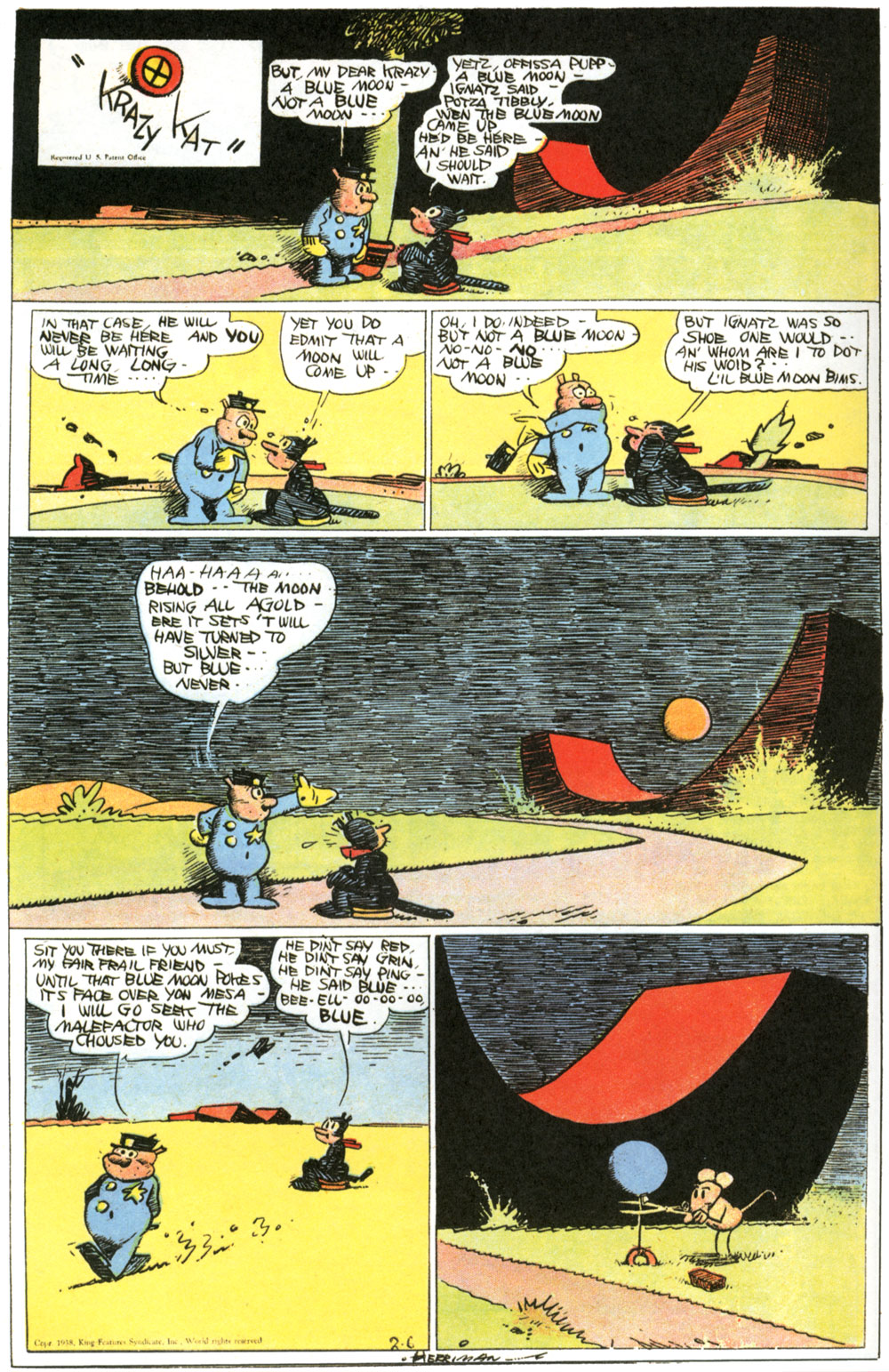

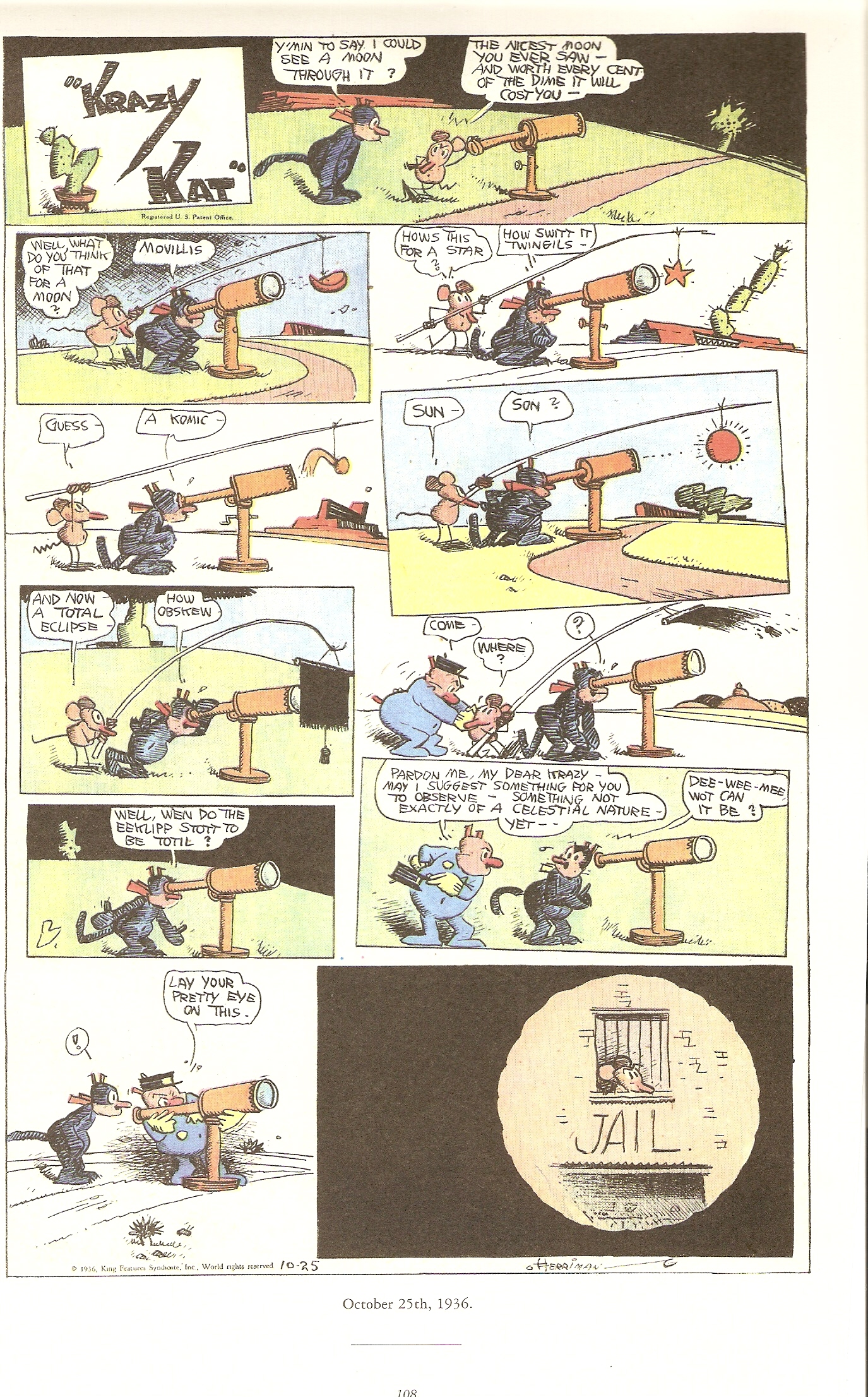

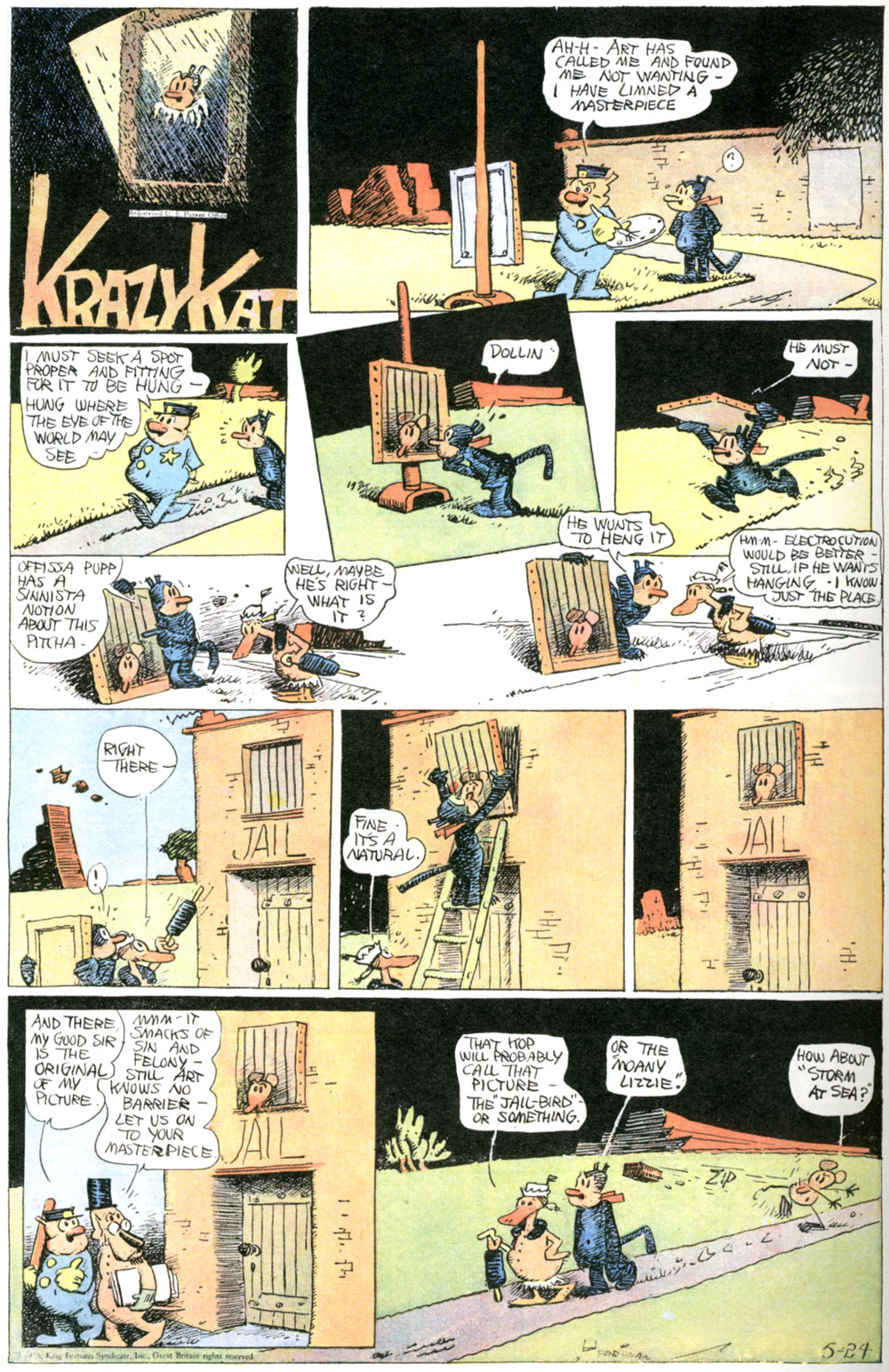

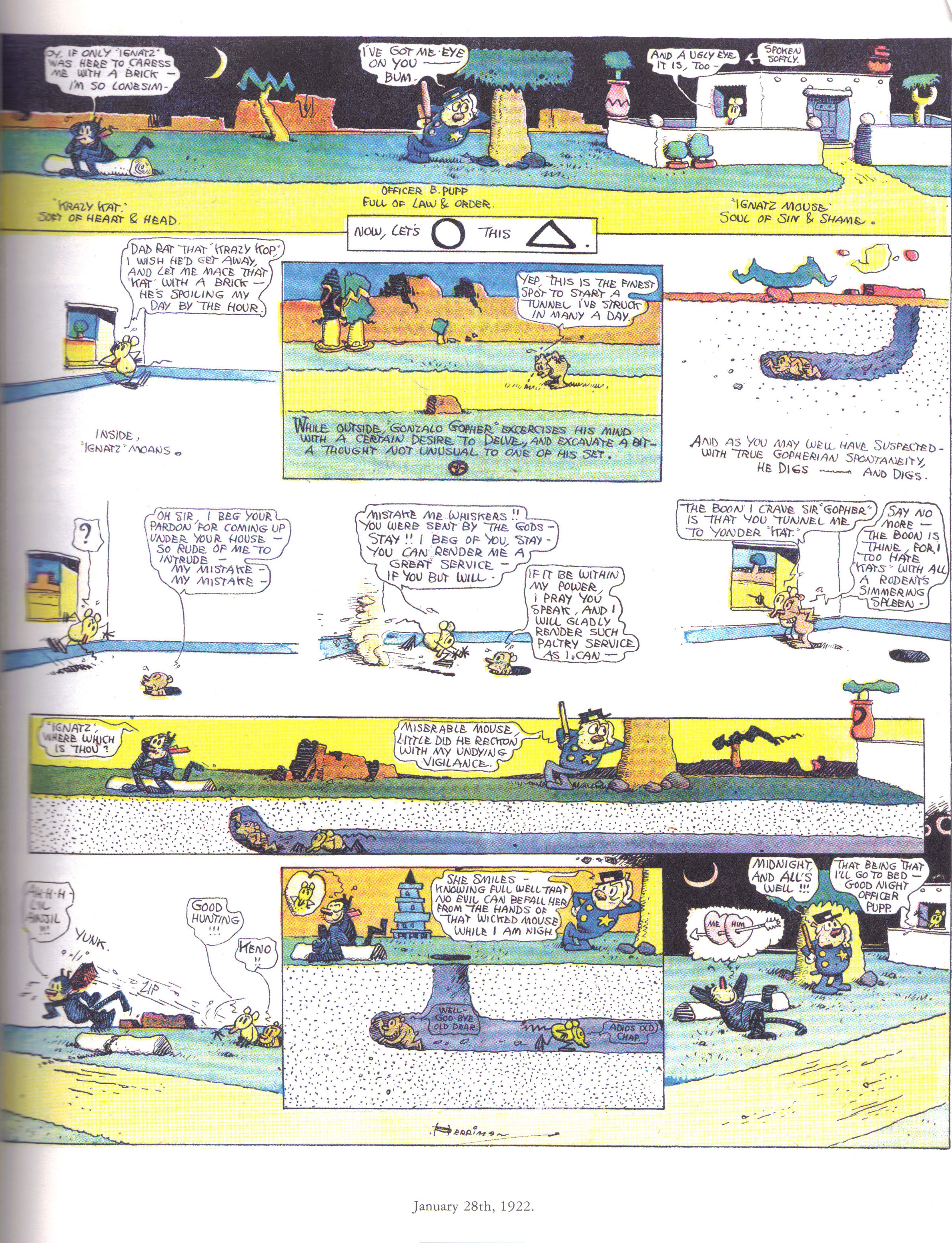

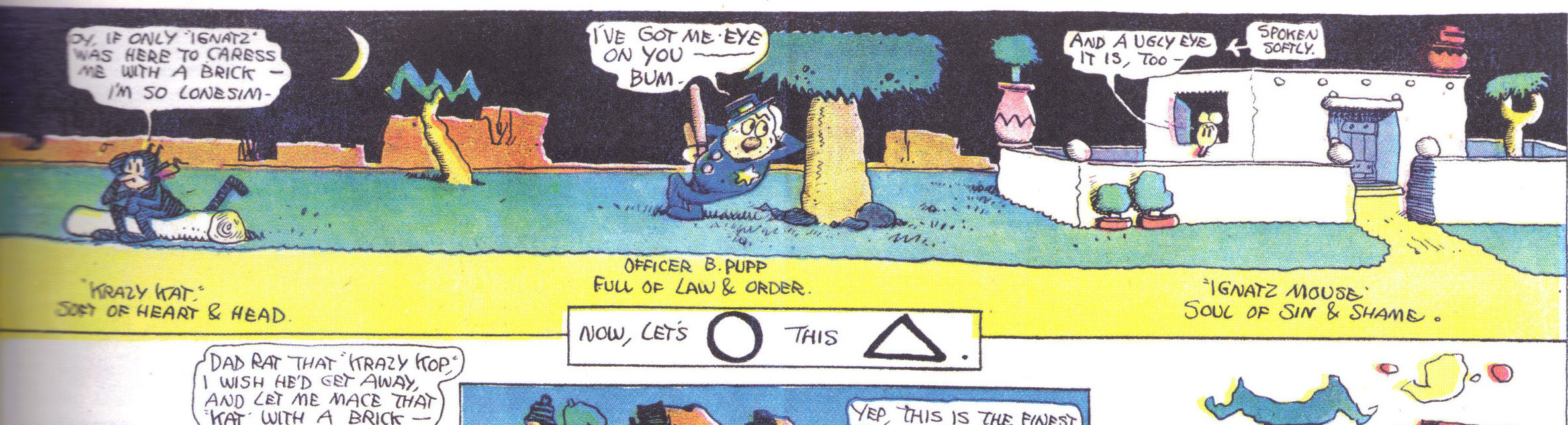

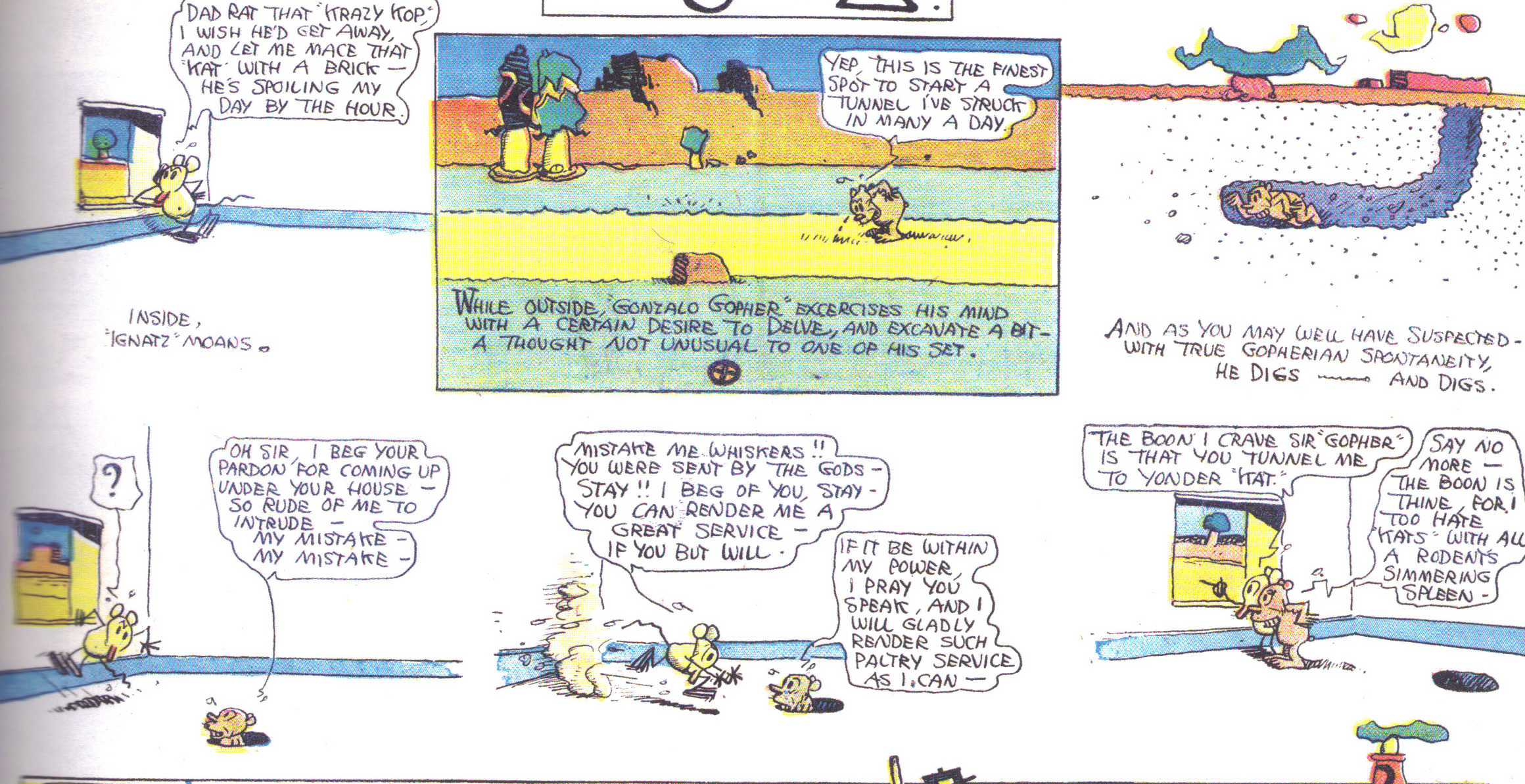

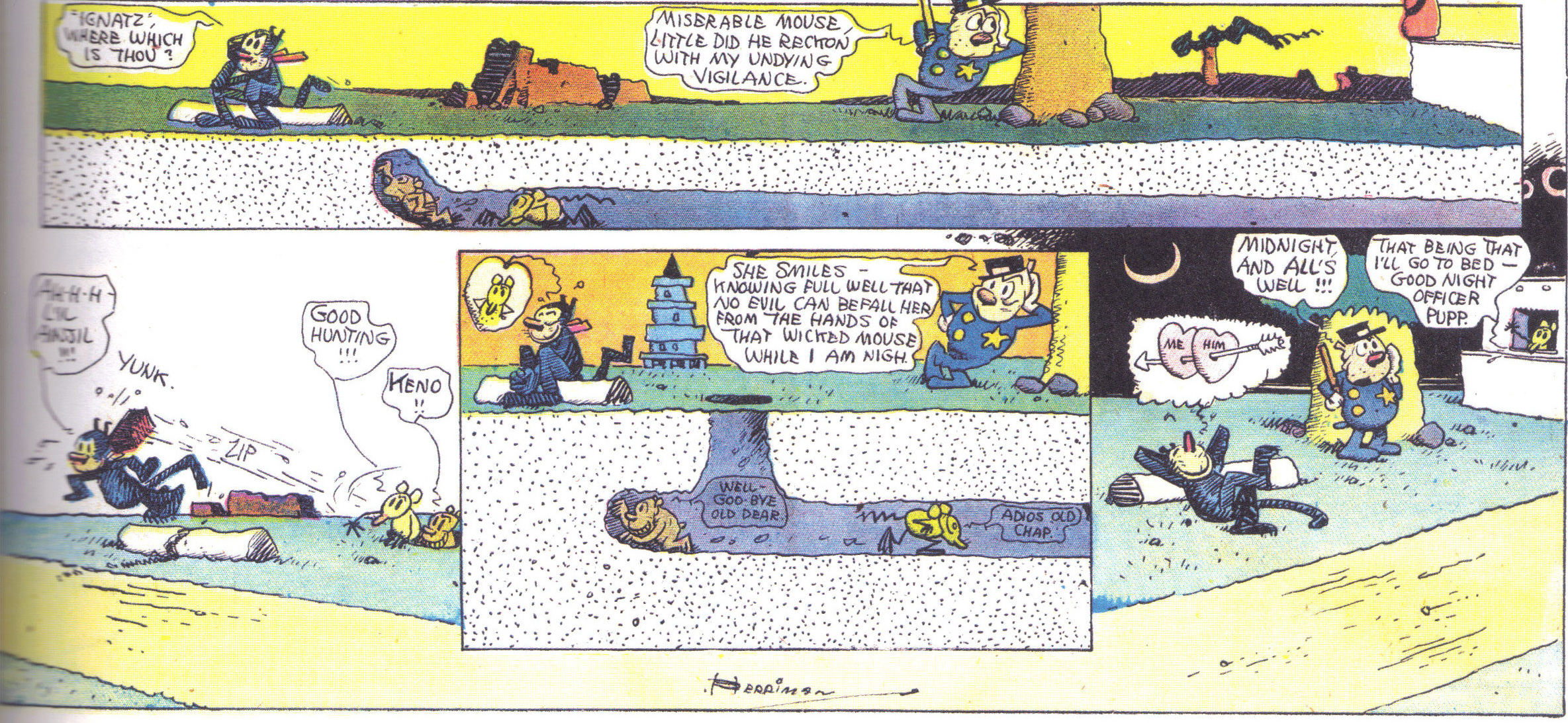

The fictional universe of Krazy Kat is weirdly both atemporal and attuned to the progression of months, seasons, and holidays. A number of episodes demonstrate this atemporality through an iterative structure according to which the panel in the top right corner and the last panel (bottom right corner) mirror one another perfectly save for one or two small differences but always to remind the reader that there will be a return to the status quo between Kat, Ignatz, and Officer Pup. Frequent visual references to the Sisyphus myth (Kat hauling a bowling ball or a wheel of cheese up a hill in order to please Ignatz who is always disappointed, etc.) echo this sense of atemporality in Krazy Kat‘s fictional universe. In one episode, dated March 25th, 1917, we see Ignatz just awakened and making a vow to himself to “make this a day of great memory.” He asks the brick dealer for his “grandest brick” but is caught in a storm and saved by Kat. In the bottom three panels we see Ignatz awaken only to decree once again that he will “do a most magnificent deed.” Strikingly, the dialogue of these three panels is word-for-word the same as the top three panels. Except perhaps that this time the reader understands the brick dealer is exploiting Ignatz’s sense of singularity by selling each new day’s brick as the brick he considers his “masterpiece.” Ignatz dramatizes a tension between the thought that “today is a special day” and the fear that “today is the same as any other day,” between the eventful and the everyday. If we read the Kat-Mouse-Pup love triangle as a kind of allegory of American life, as E.E. Cummings did, Ignatz’s willful ignorance of the repetition in his life speaks to a need to experience repetition in one’s lives as though each iteration were singular and different. But this willful blindness to the repetitiveness of his life also prevents Ignatz from appreciating the paradoxical temporality of the holidays wherein we allow ourselves to enjoy and revel in repetition by calling it tradition.

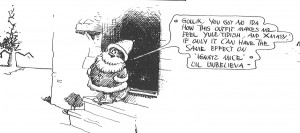

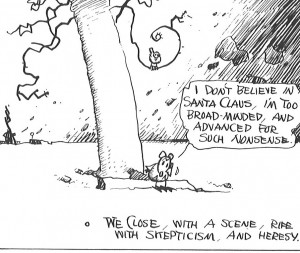

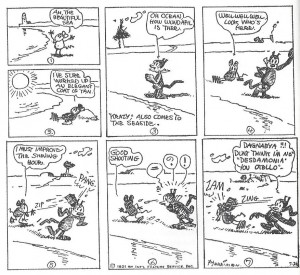

In Krazy Kat‘s first Christmas episode (12/24/1916), the brick dealer begins selling “karbon briquets” instead of bricks for the season. His sign reads, “build a house or build a fire”. When Ignatz wakes to Krazy regaling him with Christmas carols he hurls briquets through the window at the besotted caroler. Krazy gives the “brickwets” to Senora Pelona Chiwawa, the Mexican war bride and her three “fatherless pups,” who use them to stay warm. The concluding panel shows Krazy sleeping under the mistletoe with a caption beneath him that says, “merry krismis and a heppy new year!!” Structurally, this episode is not too different from any other. Aside from the various holiday references and the transubstantiation of bricks to briquets that makes Ignatz into a foiled Scrooge figure, it’s business as usual. But the Christmas episode published two years later is much more self conscious about bringing the weird temporality of Krazy Kat’s fictional universe into dialogue with the equally weird temporality of Christmas. This next Christmas special opens with Kat spying on Ignatz as he verbalizes his disbelief in Santa Claus (“I don’t believe in “Santa Claus”, I’m too broad-minded, and advanced for such nonsense”), “a scene, rife with skepticism, and heresy,” as the caption reads. Kat endeavors to restore Ignatz’s faith and presents himself to the latter dressed as Santa. Ignatz bows down in humble apology to Kat-as-Santa whose tail and characteristic speech give him away almost immediately thereafter. The last panel shows Ignatz seated in the same position, saying word-for-word the same thing he utters in the first panel while the caption reads, “we close, with a scene, rife with skepticism, and heresy.” The ironic authorial tone enables the reader to partake in Kat’s uncritical enjoyment of Christmas while also partaking in Ignatz’s skepticism towards the holiday. In an atemporal fictional universe that nonetheless seems to follow the seasonal cycles of our own, there is room for such self-contradictory positions. There is room to be both cynical and credulous about the brick dealer’s claims, room to feel certain that today will be eventful while knowing that it won’t, room to enjoy Christmas even if we know it’s a scam.