Earlier this week Orion Martin wrote a post in which he argued that the X-Men essentially appropriate the experience of the marginalized for the white and middle-class. The X-Men consistently presents itself as a comic about the excluded and discriminated against, but under the guise of preaching tolerance, it actually (as as Neil Shyminsky argues) erases difference. The only marginalization that matters is being a mutant, and every adolescent white boy is a mutant; ergo, adolescent white boys are as oppressed (hell, more oppressed) than anybody. Let us, then, pay attention to their angst exclusively.

Anyway, I thought I’d test Orion and Shyminsky’s arguments against the original X-Men comic; that’s X-Men #1 by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby from way, way back in 1963. I’d remembered it as being an awful comic, and it is that; one of those Lee/Kirby efforts where proponents of Kirby would be well served by attributing as much of the writing to Stan as possible (and as much of the art too, for that matter; this is not within a mortar shot of being Kirby’s best work.)

Part of why the comic is so crappy is that it matches up with Orion’s thesis so perfectly that it’s painful. We first see the X-Men (Cyclops, Beast, Ice-Man, and Angel) in a palatial, exclusive private school. The first few pages are all cheerful boys’ school high jinks, enlivened only by the student’s obsequious deference to, and competition for the approval of, Xavier. It’s an unbroken collage of fusty preppiness and ostentatious privilege — underlined when Angel mentions off-hand that he’s a representative of “Homo Superior.” Is he referring to his wings or his class status? It’s not clear.

Be that as it may, the plot grinds on, and we hear that a new student is coming: “a most attractive young lady!” as Xavier tells his all-male students, before even communicating her name. Said male students then cluster around the window looking out, making various lewd observations (“A Redhead! Look at that face…and the rest of her!”) We are, in short, insistently positioned with the guys; we and they sexualize her before we even see her. When the X-Men do finally meet the new recruit, they spit out various stale and uncomfortable pick up lines, culminating in Beast trying to kiss her. Thus the first effort at portraying difference in the X-Men comic, the first introduction of someone who is not like the others, results in objectification followed quickly by sexual harassment. (Jean does use her telekinesis to put Beast in his place…but then refers to him sympathetically as “poor dear,” just so we know she’s not really angry or freaked out at having her fellow students trying to fondle her within ten minutes of arriving at her new school.)

>Yet more leering at Jean.

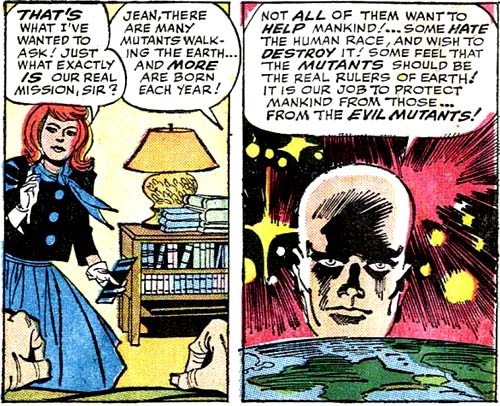

Somewhere in the middle of this edifying display of gender politics, Xavier gives with a quick speech about how normal humans fear mutants (“the human race is not yet ready to accept those with extra powers!”) and so he’s set up his luxurious refuge, where X-boys can leer at X-girls undisturbed by outside interference. He adds, though, that they have a mission to “protect mankind…from the evil mutants!”

Shyminsky points out that the X-Men basically spend all their time attacking other mutants who aren’t sufficiently assimilated; their work is to further marginalize their brothers in the name of a justice of the privileged which is never questioned. That certainly fits this story, where Magneto’s plot involves attacking a US military base and disabling armaments and missiles. Again, the year here is 1963, deep in the cold war. Actual marginalized people at the time and earlier (like, say Paul Robeson or Woody Guthrie) were able to figure out that U.S. military power was used in less than noble ways around the globe, from Cuba to Indonesia to Africa. You’d think that a self-declared Homo Superior with experience of oppression like Magneto might be able to articulate that. But, of course, he doesn’t; he’s just an evil villain whose evilness serves deliberately to emphasize the justness and general awesomeness of the U.S. military.

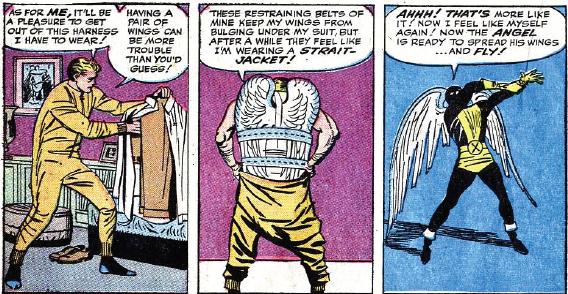

As for the X-Men’s marginalization…it seems easily doffed. The military guys aren’t scared of them, but welcome their help. The most uncomfortable scene of difference we get is a three panel sequence in which Angel changes out of his street clothes, revealing that he trusses his wings up behind him to keep them out of sight. “After a while they feel like I’m wearing a straight jacket!” he says. But no one ever questions why he has to bother to tie up his wings, or make himself so uncomfortable for the convenience of people who (supposedly) hate him. In fact, the sequence seem much less interested in Angel’s discomfort than in the ingenuity of the disguise.

Shyminsky notes that this fascination with, and eager embrace of, assimilation can be linked to the biography of Stanley Lieber and Jacob Kurtzberg, who changed their named to Stan Lee and Jack Kirby in order to be taken, like Angel, for normal humans. There’s a poignance there, perhaps, in Angel’s discomfort — Lieber and Kurtzberg’s new names may have pinched them a little at times too. But they nonetheless persevered in tightening that truss, which, in this comic at least, consisted not merely of new names, but of what can only be called a servile, deeply dishonorable acquiescence in hierarchical norms, casual misogyny, and imperialist fantasies. I hated this comic already, but as a Jew reading it as a parable of Jewish assimilation, it makes me actually nauseous. James Baldwin says that black people hate Jews (when they do hate Jews) not because they’re Jews, but because they’re white, and this seems like a fairly withering illustration of what he was talking about; a sad account of how my people (not all my people always, of course, but some of my people too often) kick those further down the food chain in a craven effort to look like, act like, and be the ones in charge. Xavier isn’t Martin Luther King; he’s a neo-con, and/or Michael Bloomberg, so charmed by whiteness that he devotes his existence to telepathic racial profiling.

So, yeah; this is not just a badly written comic, but an actively evil one. Other X-Men stories may be better — and indeed, they’d almost have to be. But at its inception, the title was a stupid, craven, explicitly sexist and implicitly racist piece of shit.