A version of this ran on Madeloud.

___________________

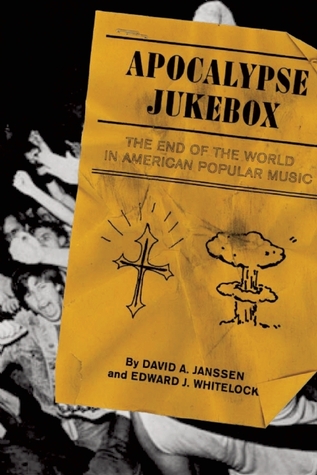

The central thesis of David Janssen and Edward Whitelock’s book Apocalypse Jukebox: The End of the World in American Popular Music is sound — there is a lot of American popular music that deals with the end times. Unfortunately, the vast majority of apocalyptic music at this point in history falls under the rubric of “metal”, a genre in which Janssen and Whitelock have no interest. Instead, the two of them are standard issue rock critics, which means that their canon is comprised of the usual holy trinity: roots rock, punk, and a couple random token black guys.

The central thesis of David Janssen and Edward Whitelock’s book Apocalypse Jukebox: The End of the World in American Popular Music is sound — there is a lot of American popular music that deals with the end times. Unfortunately, the vast majority of apocalyptic music at this point in history falls under the rubric of “metal”, a genre in which Janssen and Whitelock have no interest. Instead, the two of them are standard issue rock critics, which means that their canon is comprised of the usual holy trinity: roots rock, punk, and a couple random token black guys.

What this all means is that the Jukebox in the book’s title is probably more important than the Apocalypse. Rock’s canon, and its criticism have never really gotten out of the sixties and fifties — for Greil Marcus and all his bastard heirs, the real music still comes on 45s, or at least sounds like it wants to. For all their claims to revolution and/or apocalypse, roots rock and its criticism are both very much nostalgia exercises, compulsively referring back to…well, to their roots, in blues, country, and whatever other authentic volk music is handy.

The contradiction here is that those volk musics were, in fact, obsessed with future Armageddon, as Jannsen and Whitelock clearly demonstrate in the early, and best, part of the book. From bluegrass duo the Louvin Brothers harmonizing about retribution for sins, to the Spirit of Memphis Quartet calling the Lord on an atomic telephone, to rockabilly bombshell Wanda Jackson comparing herself to the annihilation of Hiroshima in “Fujiyama Mama”, American music demonstrated a communal fascination with Armageddon.

That “communal” bit is key. Individuals die all the time, but civilization goes on — except in the apocalyptic vision, where everybody dies, all at once, and the community itself is destroyed. Apocalypse, then, is in some ways an ultimate vision of togetherness and group identity. Whitelock and Janssen express some surprise that “Fujiyama Mama” was a bigger hit in Japan than in America — but of course it was. The song is talking about Japan, after all. Why wouldn’t the Japanese community embrace it?

Apocalypse, then, serves as a kind of social glue, a common ideology. In bluegrass, the saints will be separated from the sinners; in metal, abject nothingness, variously defined, will consume the world. Organized around apocalypse, both of these forms put a high premium on adherence to strict formal structures — dedication to a shared communal aesthetic vision. As Jello Biafra noted, no high school gym; teacher ever had as much success in getting kids to dress alike as metal does. Everybody dies together, so everybody lives together. Nobody stands out.

And in rock? Well, that’s the rub, isn’t it. There is no shared vision in the kind of critically acclaimed rock that Whitelock and Janssen are discussing. On the contrary, the whole point of the genius rockstar is a hyper-cultivated, hyper-marketed, endlessly fetishized individuality. The artists that Janssen and Whitehead have chosen to analyze are deliberately unalike — they use apocalypse in different, individualized ways. For Leonard Cohen, the apocalypse is a metaphor for his divorce; for Green Day it’s a metaphor for adolescence; for Devo, it’s a metaphor, contradictorily, for deindividuation and conformity. Regular folks may all go out the same when the fire comes, but each genius has a different end.

Whatever there other eccentricities, though, the daring individualists that Whitelock and Janssen love do share one trait in common: ambivalence. They’re all complex…or, if you prefer (and in the case of Michael Stipe, literally) inarticulate. Apocalyptic songs tend to celebrate the great simplification of the end — God will set your fields on fire, the traditional bluegrass lyrics insist; trying is not enough, roars Khanate. There’s not a whole lot of wiggle room there. But for Whitelock and Janssen, the apocalypse is yet another excuse to validate, not self-obliterating finality, but self-absorbed complexity. Dylan may insist that you have to serve somebody, but his burnt-out Beat poet doggerel mush ensures that, from song to song, it’s almost impossible to tell who — or, as the authors rhapsodize, Dylan’s audience keeps “bumping into mirrors on all sides.” Arthur Lee enjoys “playing with cacophony,” multi-tracking his voice singing different lyrics simultaneously in order to create a sense of “unreliability” and ambiguity. Devo both embraced and satirized pop success. R.E.M., through the power of refusing to enunciate, both did and did not make sense. They’re all having their Armageddon and maintaining their ironic distance from it too.

Which is to say that, as I read through this book, I started to suspect that for most of these performers, and, indeed, for the authors, the apocalypse was not so much a matter of belief as of self-dramatization. Like Samuel Jackson in Pulp Fiction, what the apocalyptic rhetoric means is less important than the fact that it is “some cold-blooded shit.” It’s a way of demonstrating rootsy bona-fides, much like boasting about your sexual prowess, or bragging about shooting your woman. The apocalypse is turned from a negation of self into a validation of it. The vision of a (supposedly) more authentic community is reified as part of some individual genius’ ambivalent contradictions. The go-to figure here is, of course, Harry Smith, whose “social music” volume of the Anthology of American Folk Music collected examples of 20s and 30s performers like Blind Willie Johnson warning of the coming end.

For critics like Janssen and Whitelock, however, those warnings become not literal calls to clean up your act, but secret subcultural testaments to Smith’s genius. They rhapsodize about Smith’s “sequencing” and about his decision to give no information about the race of the musicians he is appropriating — eclipsing their communal identity with his own liberal, proto-hippie, idealistic individualism. Smith’s final message, according to the authors, is “This is an imperfect world we have created, let us not uncreate it.” They limn this as apocalyptic — but surely it’s precisely the opposite. Celebrating imperfection, claiming that “we” have made the world — that’s not eschatological. It’s humanist.

At the end of the book, the authors more or less admit that humanism is where their sympathies lie. Working off of feminist writers like Lee Quinby, they highlight the cruelty and exclusionary nature of apocalyptic thinking, and praise Sleater Kinney for, refusing to “do ‘no future’ punk.”

It’s fair enough to point out apocalypse’s downside, certainly…but humanism has its problems as well. Specifically, to put your faith in the human (or in your rockstar heroes) is the definition of worshipping idols (and, indeed, the authors point out that poor John Coltrane has had a Christian church established in his name.) The human isn’t divine; to pretend that it is, you have to steal mojo from somewhere — a communal past, say — and then pretend that that theft is an act of generosity or continuity, betraying the faith you claim to espouse. A personal apocalypse isn’t an apocalypse at all; it’s blasphemy. If rock is the devil’s music, as Janssen and Whitelock ambivalently claim, it is not because it embraces apocalypse, but because it doesn’t.