This piece originally appeared on Splice Today.

___________

If you know one thing about black metal, it’s probably that some performers are racist shitheads who burn churches. Jessica Hopper recently published yet another article retailing the various unpleasantnesses committed by Varg Vikernes of Burzum. She did vary the formula a little, though, by acknowledging that not all black metal performers are Nazis. Instead, she argued that all black metal performers have to deal with the fact that the music is originally, inevitably, associated with unpleasant ideologies.

“The genre’s reluctant fans can be divided into a few apologias. There are those who go for the sheepish “but it’s so good I can’t help it” (the artist is creepy, his work divine). And others subscribe to the fantasy that if you don’t cosign the artist’s belief, their platform, their perversion, if you don’t understand what they are singing about, if the song isn’t explicitly promoting an agenda, though the artist may be, that you are less of a participant. Another common excuse is that the lyrics are unintelligible (or not in English, so they don’t “count”), and they are listening to black metal just for the heavy atmospherics.”

As a casual fan of black metal myself, I don’t think I necessarily make any of these apologies. And that’s for the simple reason that there are just tons of black metal acts that aren’t any more ideologically noxious than any other music on my hard drive, and less ideologically noxious than some. Porter Wagoner singing murder ballad after murder ballad about how cool he is for shooting his cheating woman or Janis Joplin signing off on blackface iconography for her album cover seem significantly more dicey to me than listening to Katharsis theatrically shrieking about witches and satan.

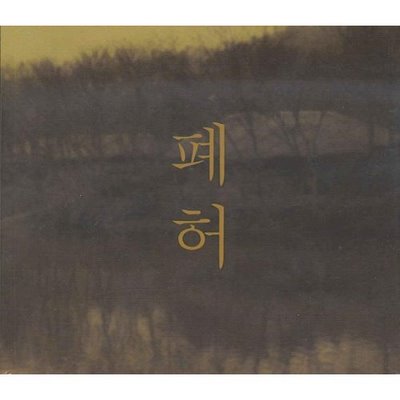

It’s true that black metal is focused on evil and death and genocide. But being interested in those things doesn’t have to mean you’re a Nazi. It could mean that you’re Gorecki — whose droning ambience isn’t all that far removed from black metal’s aesthetics, as it happens. And if it sounds crazy to think that Gorecki’s explicitly anti-Holocaust message could find purchase in black metal, I would direct your attention to Pyha, an explicitly pacifist artist whose music sounds like tortured metal emitting a long, sustained groan of lament.

Pyha, a Korean who made his sole album when he was 14 years old, is obviously an oddball. But there are lots of oddballs in black metal. Another of my favorite performers, Botanist, plays hammered dulcimer and preaches plant supremacy and fealty to the forest. The band Frost Like Ashes is part of a small but non-negligible group of Christian unblack metal artists, who tend to sound exactly like black metal except that instead of talking about blood and the pit, they talk about blood and the cross, or about blood and the evils of abortion. And then there are folks like Enslaved who just like to pretend they’re Vikings. Or performers like the black/doom outfit Gallhammer who are dedicated to the proposition that Japanese women can make a noise as terrifying and evil as any Scandinavian dude.

There are also bands like Drudkh who (as the album title Blood in Our Wells indicates) are in fact anti-Semitic assholes. But the reason black metal is defined by anti-Semitic assholery isn’t because all black metal musicians are anti-Semitic, or even that there’s a preponderance of anti-Semitic facists in black metal. It’s because black metal isn’t all that popular, but anti-Semitic assholery makes a good story. Hopper argues that black metal fans have to face especially difficult questions about their music and aesthetic preferences. But it’s not black metal that’s obsessed with fascism; it’s Hopper and buzzfeed and mainstream venues in general. I tried to pitch a piece about how black metal isn’t fascist to a number of largish mainstream outlets. One editor said what I presume the rest of the editors were thinking: this is too niche. Or, translated, an article about how black metal isn’t fascist isn’t something anybody cares about. It’s the fascism our readers want to hear about; without that, you’ve got nothing.

Which isn’t to say that Hopper’s article is terrible, or that the issues she raises are completely irrelevant. How do listeners’ ethics interact with their aesthetics? Why do people like to pretend to be evil? Why are they fascinated by genocide? Those are all interesting questions. But they aren’t all the same question. Using black metal to treat them as such is more about demographics and hit counts than it is about looking for answers.