For my temporary stay here at the Hooded Utilitarian, I’ll be doing a series of pieces on the intersection of comics and related media with queer genders and sexualities, including how these issues have touched on my own life. I thought I’d begin with the gender politics of the Ghost in the Shell franchise.

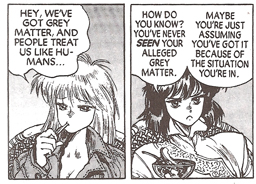

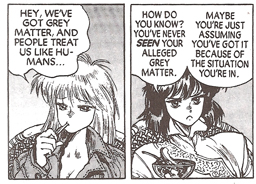

Two panels from the Ghost in the Shell manga; Motoko Kusanagi points out to a colleague that they can’t really prove that they’re human.

It was as a freshly-minted teenager that I was first captured by Mamoru Oshii’s original film adaptation of Ghost in the Shell. I was at a transitional point in my life, having just been transplanted into a new family and still learning to grasp uncertainties around gender, sexuality and my own body, and Oshii’s Motoko Kusanagi did something for me. She fulfilled a function, acting as an icon of strength outside of the conventional definitions of gendered behavior – and the borders of human life – with which I was familiar. I was able to construct a narrative around her which served a desperate need for some model of humanity I could relate to.

Harry M. Benshoff and Sean Griffin, in Queer Images: a History of Gay and Lesbian Film in America, write about this as a common queer spectatorial experience:

“…the desire to see queer characters onscreen was an important one. Such images could let isolated queers know that other queers existed and how they possibly looked, acted, or lived their lives. Such images could validate a queer spectator’s very existence, even if the images were (as they usually were) stereotyped, derogatory, or even monstrous. Queer audiences thus learned how to read Hollywood films in unique ways – often by looking for possible queer characters and situations while ignoring the rest. As Henry Jenkins explains in his study of media fandom, specialized audience members (such as queers) learn how to ‘fragment texts and reassemble the broken shards according to their own blueprints, salvaging bits and pieces of the found material in making sense of their own social experience.’ That process formed the basis of queer reception practice for most of the twentieth century.”

Many films became widely known for their queer readings – All About Eve and The Wizard of Oz being prominent examples. Queer filmmakers such as James Whale and Dorothy Arzner encoded queer signals in their work, and queer overtones were present with varying levels of menace and stereotype in a variety of classic films: The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, The Old Dark House, Queen Christina, Rebel Without a Cause.

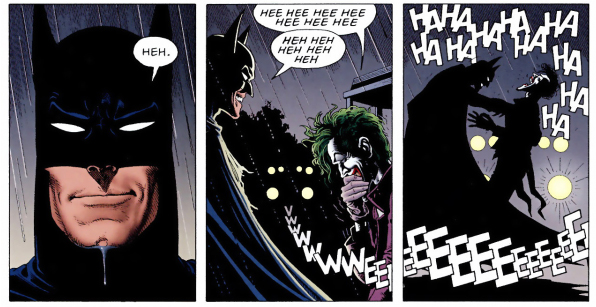

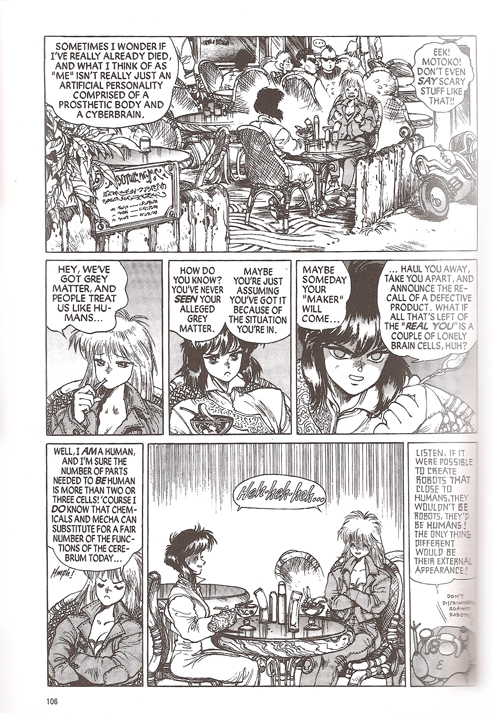

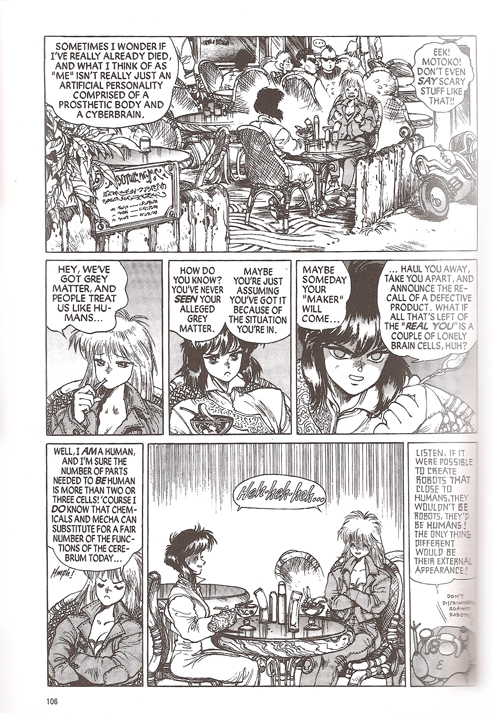

Although it’s difficult to exactly describe what made Ghost in the Shell and its lead character so appealing to me, certain anchoring points of that appeal are in hindsight quite obvious. Motoko Kusanagi is at once powerful and beholden to power, at once commanding and enslaved to uncertainty. She is constantly on top of her situation, always the quickest of mind and fleetest of foot; in an elite team of cyborg special agents, her dominance is unquestioned. Yet, she comments to Batou after going diving that while her body may be able to process beers in minutes without a trace of hangover, the body which allows her such control is completely owned by the government for which she works. Were she ever to leave Section 9, she would have to leave her body at the door along with her uniforms and equipment; she retains her power only so long as it is used according to the wishes of those with greater power still. Neither can she be certain as to her own origins; “Motoko Kusanagi” is stated in at least one iteration of the franchise to be a pseudonym, and even though in at least one case she’s given childhood memories, she can never be certain they weren’t simply programmed into her head. In both the first Oshii movie and the original comic, she points out to a co-worker that she can’t prove that she’s not just an artificial personality programmed into a cyberbrain; indeed, her inorganic body leaves her open to being mistaken for a robot, and in the comic, she is – by a sexbot collector, no less. She is at once heroic and very relatable for someone as mired in identity uncertainties and as alienated from those around them as my 13-year-old self was.

A page from the original Ghost in the Shell manga: the Major discussing with a colleague the definition of “human,” and the impossibility of really knowing if either of them is human.

Then, of course, there is her gender encoding. There seems to be within geekdom, and popular culture at large, a sacred circle of acceptable gendered appearance and expression for “tough chick” characters outside of which creators (mostly cisgender [non-transgender] men, of course) very rarely step. The territory outside of this circle is in one way or another too uncomfortable for the assumed male gaze of the audience – too “mannish,” too far outside of binary conceptions of gender, too little interested in catering to what is understood to be hetero cisgender male taste. The hetero cis male majorities within fandom certainly take part in policing the sacred circle’s boundaries; I’ve seen forum threads ridiculing designs of female characters for being just a bit too masculine, too square of jaw, too muscular, not enough designed for sexual objectification. Even Xena and Buffy, famous girl-power icons, are well within this sacred circle. Oshii’s Motoko Kusanagi is not. Such characters can hold a totemic power and be quite alluring and empowering, as any Rocky Horror Picture Show fan can attest.

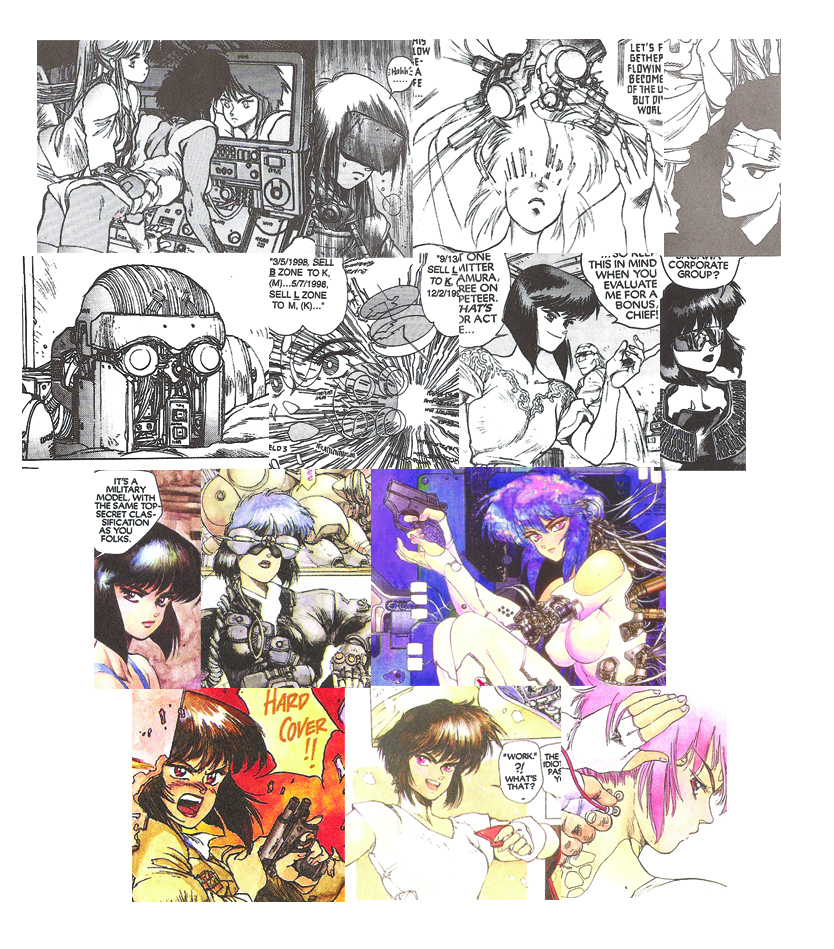

Motoko Kusanagi as Mamoru Oshii and his team constructed her: well outside of the circle of fanboy-safe “tough chick” gender expression, and well outside of Masamune Shirow’s own vision.

The incident in the manga in which she is mistaken for a robot by a lecherous male sexbot collector draws attention to another significant way in which the Major is unfree. Although Oshii’s construction of her gender encoding steps firmly outside of the sacred circle of acceptability and grants her periodic nudity a sort of liberated power only fully available in absence of the obvious tropes of objectification under the heterosexist, cissupremacist male gaze, this was clearly never Masamune Shirow’s intent. In fact, Ghost in the Shell is an exercise in essentialism; the idea of a ghost – an essence – existing within the body forms the very title of the franchise. This essence grants a body personhood, regardless of whether that body is organic or manufactured. Shirow goes even further in embracing the “spiritual essence” narrative, endorsing the spiritualist concepts of souls and extra-sensory perception. His essentialism allows him to elide the obviously severe implications of cyborgization, ghost dubbing and cyberbrain technology for social constructions of gender and gendered expression. By assuming the existence of essential differences between (feminine, “female-bodied,” male-attracted) women and (masculine, “male-bodied,” female-attracted) men, he is able to skirt these implications and resume policing gender in ways that please his gaze and keep the gendered underpinnings of the erotic fantasy that is Motoko Kusanagi intact.

In the original Ghost in the Shell comic, as in Appleseed and other Shirow works, the assertive and militaristic female lead is in many ways kept in her place: put in highly male-gaze sexual attire and situations while male characters are frequently designed in ways that are clearly meant to be read as at least unsexual, and at most quite ugly, paired with enormous and extremely masculine male leads (Briareos, Batou), shown breaking down in tears while those male leads remain stoic. Their environments are filled with feminine female characters, frequently in subservient roles (informational robot, nurse, assistant, sexbot, even wall decoration), and masculine men in commanding positions (bureau chief, politician, general, weapons dealer, government council member, commando, company president). In fact, there is a sort of “femdom” role-reversal narrative to Motoko in particular. She seems to provide titillation to the presumed hetero cisgender male reader by deviating from her own assumed feminine nature; this excitement could not be had if the roles, and the rationale for their existence, were not re-asserted in the first place. His essentialist logic prevents Shirow from considering, for example, the social implications for a male-assigned/male-identified person of having himself transferred to a body which consists of a box with legs and manipulators (the president of Hanka Precision Instruments) or the logic of using “he/him” pronouns on an intelligence born in cyberspace, and whose first physical body is presumably meant to be perceived as “female” (Project 2501/the Puppet Master).

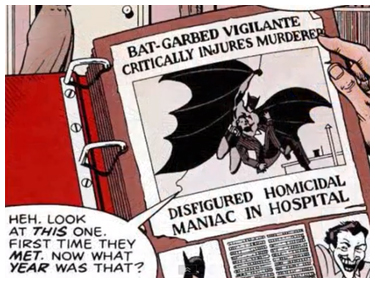

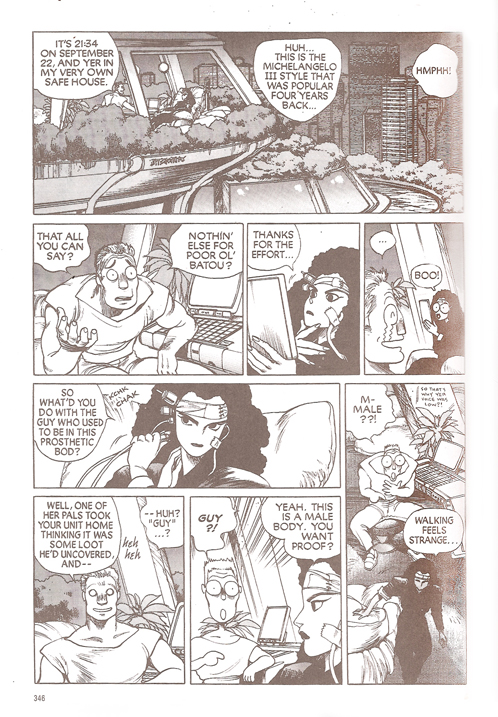

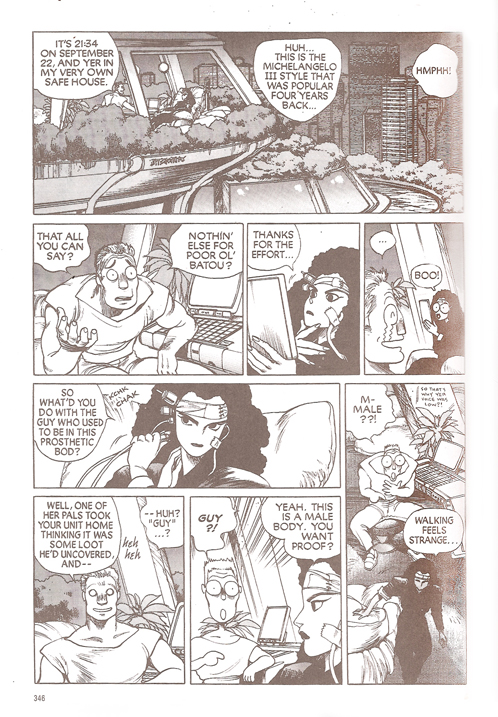

This thinking is fully exposed in all its spectacularly thin logic at the end of the comic. The Major has fused with Project 2501, and Batou has transferred Kusanagi/2501 into a new body, long-haired and feminine in appearance. Kusanagi/2501 informs Batou, to his surprise, that zir new shell is that of a “guy.” Confronted with his shock, ze replies, “Yeah. This is a male body. You want proof?” The reader is led to believe that zir new body has a penis, which apparently settles the question of its “maleness.” Bodies are not only sexed but inherently gendered, the transcendence of human bodies and brains be damned. A body can throw all sorts of signals outside of those approved for “men,” but as long as it has a penis (and no significant breast tissue, one guesses), it is sexed male. Motoko/2501 goes off to find a more suitable, “female” body. The Major can even merge with a cyber-intelligence, but as long as she inhabits a body, she cannot escape the social slavery of coercive gender roles to which all human beings are subjected. Even if she were to transfer to a masculine, male-assigned body, she would only trade one set of social strictures and assumptions for another. She might find herself more or less suited to the body’s advantages and disadvantages and to the social roles it would shove her into, but she would be restricted either way.

I cannot imagine how Masamune Shirow would respond to being confronted with a transgender person of non-binary gender such as myself. As much as I admire him as an artist and storyteller, I’m not sure I want to know.

Shirow’s big reveal at the end of the original Ghost in the Shell manga: genitals are destiny! The divide between “male” and “female” must be maintained, even when the “woman” in question is actually the fusion of a previously female-assigned person with an autonomous intelligence born in freaking cyberspace.

Like other queer and transgender people, I’m used to scavenging for my queer and gender-variant stories, situations and characters amongst works made by overwhelmingly cisgender, predominantly heterosexual creators in fields dominated by men and by male gaze. This scavenging process can be incredibly gratifying, but also deeply problematic. It means embracing images of gender variance and queerness which are built to fit the perceptions and satisfy the desires of people who are not queer or trans, and may know little of real queer and trans people’s lives. These images can be as coded, as stereotyped, as condescending, as negative and as thoroughly exoticized today as they were decades ago. It can be deeply frustrating finding one’s empowerment in yet another character created as some cisgender straight guy’s wank fantasy, and cisgender straight women’s wank fantasies often aren’t much better. Just as frustrating, if not moreso, can be to see powerful and defiantly non-gender-conforming characters “put in their place” by cis straight male fans (and, again, sometimes cis straight female fans) eager to turn them into fodder for yet another tiresome role-reversal or power-stripping fantasy. This is done in the form of constant commentary within the fandom, doujinshi, slash, or simply fan art which modifies these characters’ gender coding in various ways and drags them back into the sacred circle of acceptable gender variation. However, it doesn’t seem sensible or right to allow these norm-reinforcing readings center stage. Benshoff and Griffin again:

“As critic Alexander Doty describes his own spectatorial response to popular culture in his book Making Things Perfectly Queer, ‘I’ve got news for straight culture: your readings of texts are usually ‘alternative’ ones for me, and they often seem like desperate attempts to deny the queerness that is so clearly a part of mass culture.”

This is the part where I go out on a limb.

I’m no semiotician or Theorist, but I think there’s something interesting going on here. If we refuse to accept Masamune Shirow’s essentialist assumptions about gender and instead focus on the act of gender as it is “performed” by the fictional character on the comics page, all sorts of interesting possibilities are opened up. Even laboring under the assumption that Motoko Kusanagi is bound by an underlying essence, we must admit that this binding essence is fictional – that in fact “Essential Motoko” is a construct we amalgamate out of images and ideas accumulated from consuming the Ghost in the Shell franchise in its various forms. Abandoning this idea, we are free to focus on the Major as she in fact is: a series of images and text snippets juxtaposed. Seen this way, gender can be read into just about everything: into the whole book, into whole characters to be sure, but also into scenes, pages, panel sequences, environments, color/tone palettes and individual colors/tones, outfits and items of clothing, poses, facial expressions, speed lines, patterns and symbols, inking techniques, even single lines. The changes in gendered expression from line to line, color to color, face to face, panel to panel are often tiny, but they are important because they provide an entirely different image of gender in comics. This image is not one of an immutable essence limited to characters and rarely or never changing, but as an everpresent jumble of tiny shards of signification, only semi-coherent at best and only even pushed into appearing as constant (if fluid) by the reader’s ability to imagine the gaps in information between panels – the device of “closure” described in Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics. Gender overgrows in every direction, abundant shards of it popping up wherever the particular reader’s subjectivity allows it; it is subjective, certainly, and also cumulative and temporal, agglutinating and morphing as the reader reads and re-reads, consumes new additions to the franchise, looks at new pieces of fan art, comes to greater understanding of plot points, digests criticism. Each of these experiences provides an abundance of these shards of gendering for the reader to plug into their gender-concept of the entire franchise, the individual story or character, the individual page. The reader is selective in doing this, and the shards from which they select appear different as the reader acquires different sets of eyes.

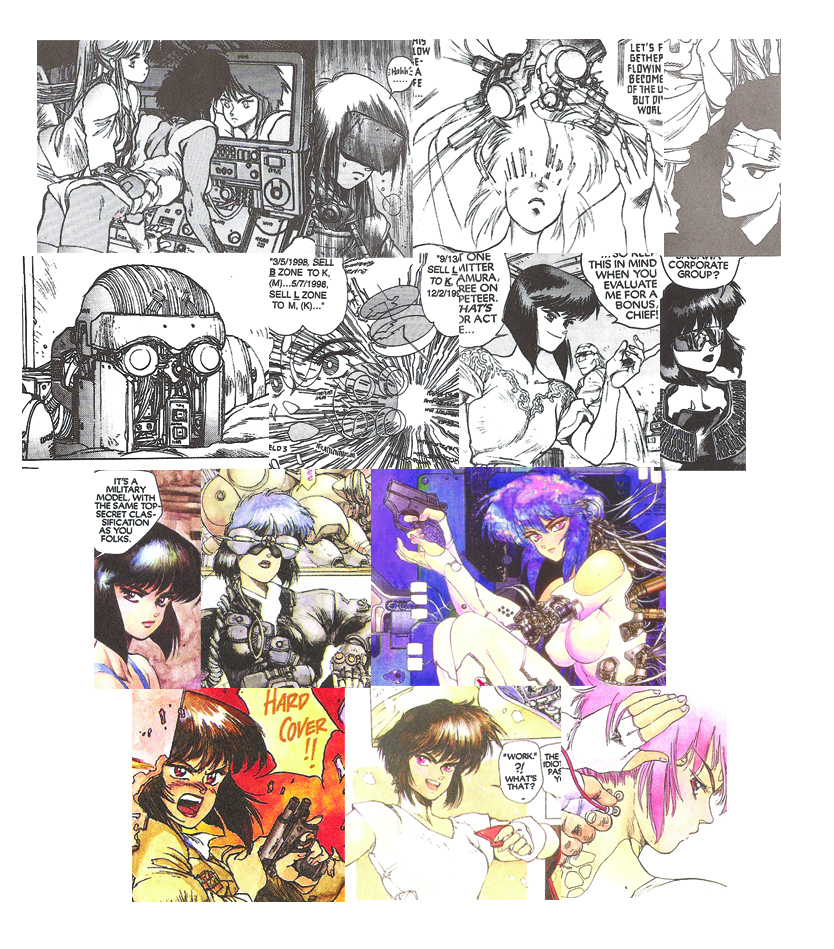

Various different Motokos from the original manga, each with her own marginally coherent assemblage of gendered signals to give off.