This piece first ran on Comixology.

_______________

Quentin Blake’s 1984 illustrated children’s book, The Story of the Dancing Frog, starts off innocuously enough. A young boy, Jo, asks his mother to tell him a story of their family. She obliges by launching into the story of Great Aunt Gertrude, who married a sailor “with a black beard and smart uniform.” The sailor (who is never named) is away often, which is sad, but, as the mother notes, “they were happy when they were together, and they had a house by the sea and Gertrude would watch for his ship returning.”

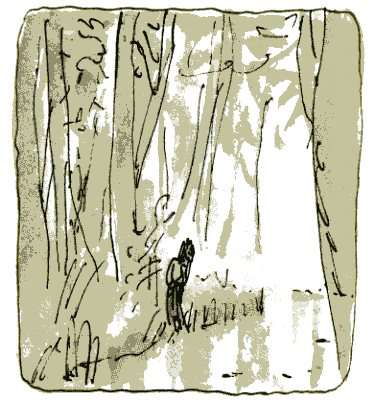

Then one day, as you’ve probably guessed, his ship doesn’t come back, and Gertrude receives a letter saying he has drowned. “You can imagine how awful it must have been to get a letter like that,” mom says. Gertrude goes out to the river to walk alone, and thinks about throwing herself in “so that she could be drowned too, like her husband, and finished.” Blake’s sketchy pen and watercolor illustration portrays that moment from some distance, as if Gertrude and the river around her are fuzzing out, preparing to dissolve.

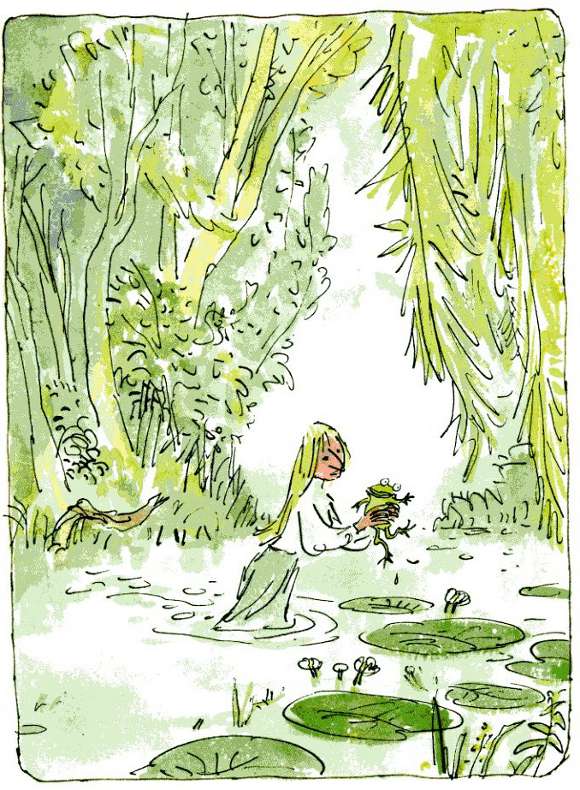

Instead, though, she looks up and sees a frog dancing on a lilypad. Without quite knowing why, “she walked into the water and picked up the frog and carried it home.”

The picture of Gertrude picking up the frog is both moving and goofy. Gertrude is half in the water, her facial expression hard to read. The trees form an arch overhead, and her dress is pulled back by the water. It’s a ritual and sensual scene, like a rebirth or a wedding. The frog, on the other hand, is clearly not quite up to the role of Prince — it looks helpless and bizarrely cheerful with its googly eyes and gangly body, no more aware of the affection it’s inspired than an infant. Its obliviousness, though, only makes the moment more poignant. Without knowing it, it is both lost husband and child that never was, a lifeline that cannot possibly bear the weight put upon it.

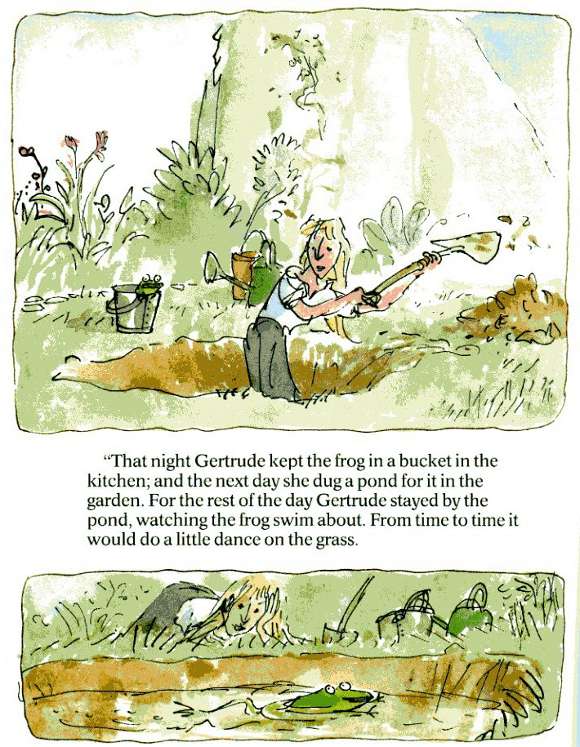

Or maybe it can. Gertrude goes back home and digs a hole in her backyard. The hole is a pond for the frog, but Blake’s drawing makes it look, also, like a grave. Then she fills the hole with water, so the frog can swim in it.

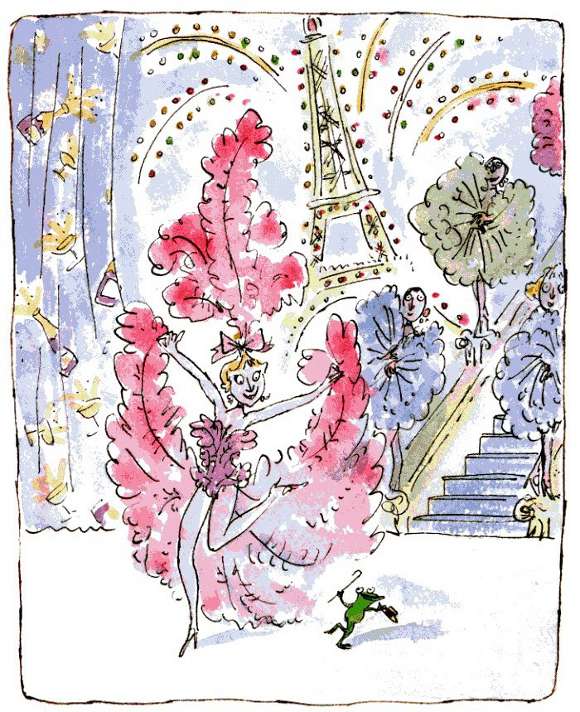

Quickly after that, the story moves away from grief, as well as from all semblance of realism. Gertrude and the dancing frog (whose name, or perhaps just his stage name, is George) go on the road, steadily growing more and more successful. George performs tricks and dances in glamorous settings, a dashing little blob of green.

There are some other incidents: Gertrude turns down an offer of marriage from a lord; George is caught in a hotel fire and must leap to safety into a bucket of water from the thirteenth floor. But basically that’s the story. Gertrude loses her husband and finds a frog and spends her life with it. When I read it to my son, he couldn’t for the life of him figure out why it made me cry.

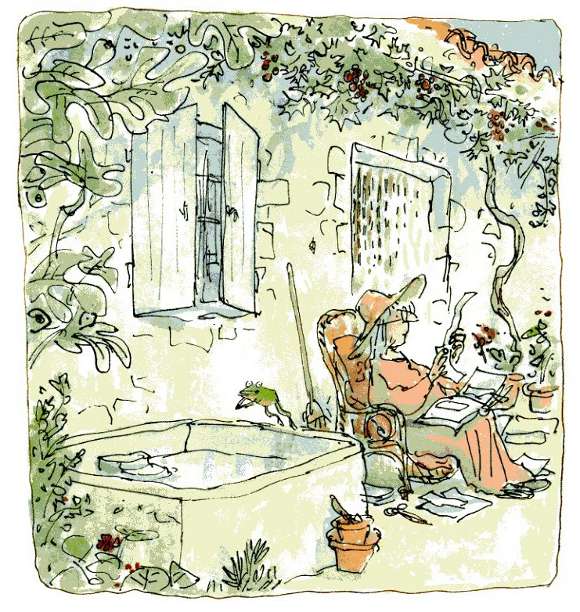

The reason, of course, is that (the possibly nameless) George both is the (nameless) husband, and is not. George comes out of the water that the husband went into, and takes his place — living the life with Gertrude that the husband lost. Gertrude, on the other hand, never comes out of the pond; her whole story is her grief, an impossible dream of happiness. And yet, at the same time, she does come out of the pond, holding a friend (a child?) around which she manages to build a life, not in spite of her grief, but because of it. When Jo wonders why Gertrude chose the frog over the Lord’s offer of marriage, the mother answers “Well, I suppose you could say they looked after each other over the years.” And, indeed, we see at the end scenes of an aging Gertrude and an (impossibly old at this point, surely) frog entering their twilight years in the south of France. They live amidst idyllic watercolors and beside an ever-present little pool, a reminder of where George came from and where someone else went.

At the end Jo has one more question.

“Was that a true story?”

“More or less.”

“But frogs don’t normally dance, do they?”

“Not normally, no.”

“And no one could really catch a frog and put it on the stage.”

“You can do all kinds of things if you need to enough.”

The fact that Jo and his mother never mention a father in the family gives the story an added, speculative resonance. This is intensified, perhaps by the sepia palette used to illustrate them, which is similar to the muted colors used on Gertrude after she hears of her husband’s loss. The book, as Quentin Blake has pointed out is called, not The Dancing Frog, but The Story of the Dancing Frog. Perhaps what came out of the river is not a frog, but a fairy tale — a dream to live out as life till one is ready to join one’s heart beneath the waters.