A version of this review first appeared at the Chicago Reader.

__________

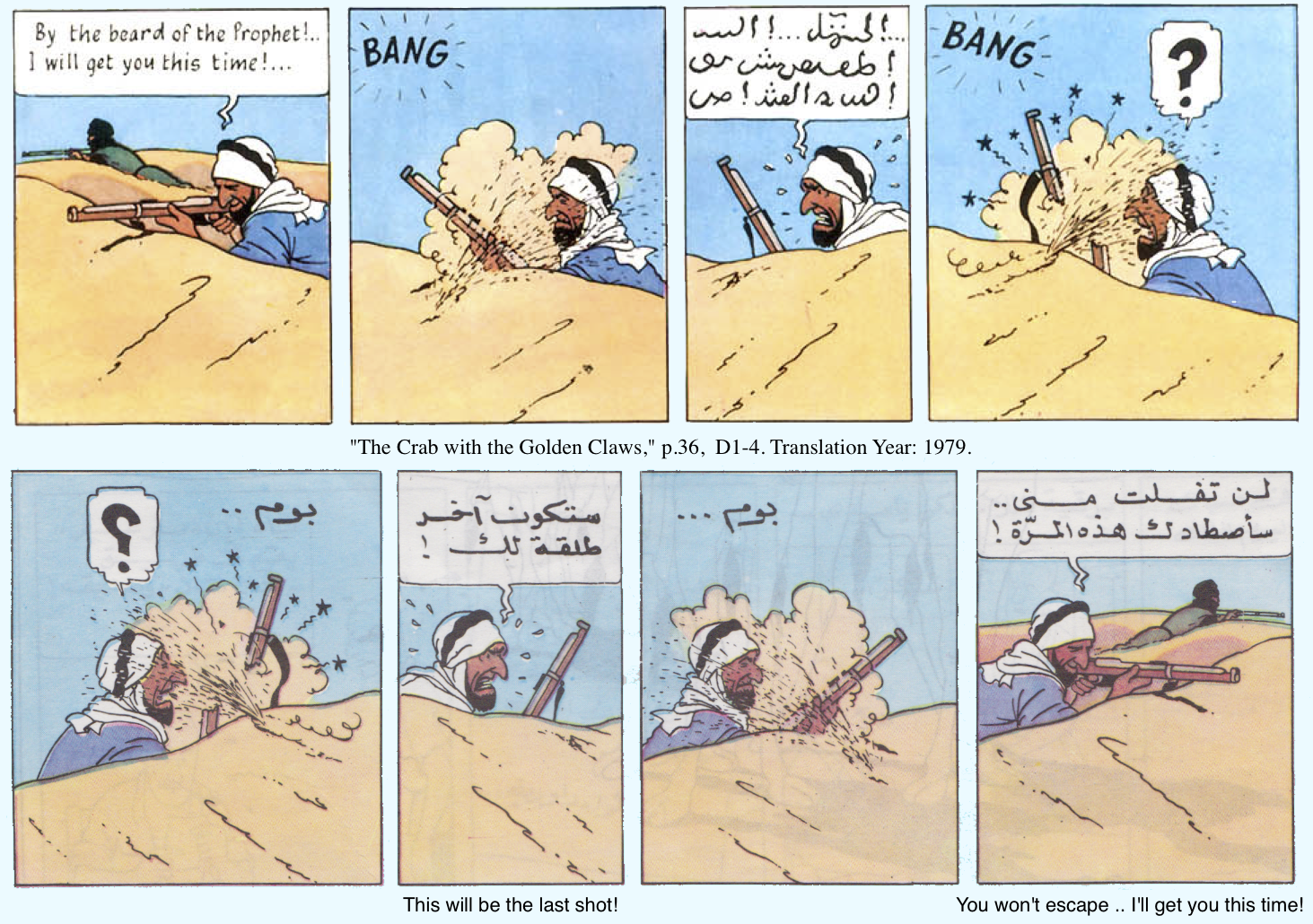

“It was shocking that in a city bursting with parade enthusiasts and curious tourists, a pair of European women who stayed less than an hour were the only white faces in the crowd other than ours,” write Yuval Taylor and Jake Austen in their new book Darkest America: Black Minstrelsy from Slavery to Hip-Hop. (100-101) The two are describing their experiences at Mardi Gras, where they went to watch the Zulu parade, one of the few places in contemporary America where African-Americans will wear blackface as a matter of course. Taylor and Austen describe their own experiences at the parade in order to convey the manic strangness of carnival; to show why and how even blackface can be normal there. At the same time, though, by highlighting their presence at an all-black parade, they emphasize their whiteness — and, paradoxically, their adoption of blackness. The Mardi Gras description is, at least in part, about two white authors momentarily joining the black community. In that sense, the passage can itself be seen as a kind of literary blackface.

This is not to criticize Taylor and Austen. On the contrary, this very mild stumble — if it even rises to a stumble — serves mostly to throw into relief how very surefooted, thoughtful, and perceptive they are for the bulk of the book. This is no mean achievement, since black minstrelsy — the practice of blacks donning blackface and/or performing routines associated with minstrel shows — is surely one of the most charged and uncomfortable topics in American pop cultural history.

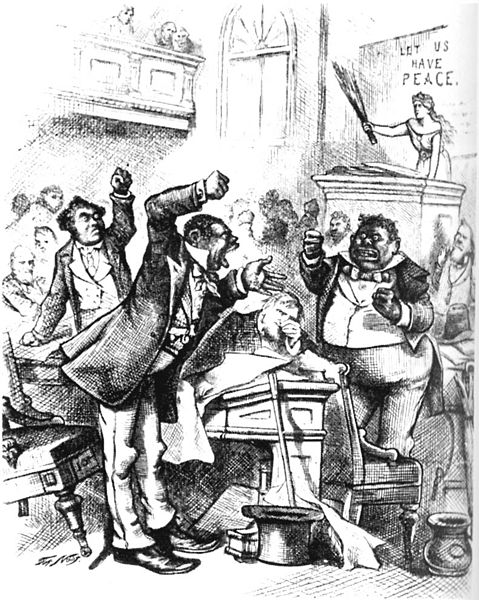

In the late nineteenth and early 20th century, blackface performances by whites perpetuated vicious racist stereotypes of happy, lazy, stupid chicken-eating, watermelon-slurping, vacuously-grinning darkies. And yet, as Taylor and Austen show, blacks themselves have been long time, and even enthusiastic participants in the minstrel tradition. From Louis Armstrong to Flavor Flav, minstrel clowning and tropes have been central to black American music and black American comedy.

What, then, did blacks get from minstrelsy? Was it an example of false consciousness, with African-Americans duped into adopting hurtful stereotypes as their own? Or were black entertainers forced to adopt minstrelsy to make a living in a white-controlled entertainment industry?

Such explanations have been staples of the longstanding black anti-minstrelsy tradition, from Richard Wright to Spike Lee’s 2000 film Bamboozled. But while Taylor and Austen have great respect for anti-minstrelsy’s commitments and aesthetic achievements, they mostly reject its conclusions. Black minstrelsy, they argue convincingly, was not, at least for the most part, the result of self-deception or coercion. No one, for example, forced the politically engaged Paul Robeson to record “That’s Why Darkies Were Born,” a minstrel type song which told blacks to labor cheerfully in the cotton-fields and “accept your destiny.” (208)

Instead, Taylor and Austen argue, blacks used minstrel traditions in a number of different ways. Sometimes, they deployed it as a critique— as Spike Lee does in Bamboozled. Sometimes, they adapted and subverted racist messages, as in Robeson’s version of “That’s Why Darkies Were Born.” Robeson, Taylor and Austen argue, treats the song as a spiritual, in which blacks shoulder suffering, hardship and injustice on their way to the Promised Land. Rather than a justification of racism, in Robeson’s hands the minstrel song becomes a dream of liberation. In a similar vein, the great early-20th century black blackface performer Bert Williams injected pathos and nuance into his performances and songs, undermining the racism of minstrelsy by emphasizing the humanity of his characters.

While black minstrelsy could be used consciously to confront or undermine racial tropes, however, that does not seem to have historically been its main appeal to black performers and black audiences. On the contrary, in many cases, Taylor and Austen suggest, minstrelsy was enjoyed by blacks in much the same way it was enjoyed by whites — as low humor and nostalgic escapism. Southern hip hop performers who gesture towards minstrelsy with clowning about chicken or watermelon do so because they enjoy such humor…and aren’t going to be embarrassed about it just because various cultural arbiters say they should be. Similarly, Louis Armstrong sang “When Its Sleepy Time Down South” — with its evocation of the lazy “dear old Southland” — because a nostalgic vision of ease and plenty appealed to him and other blacks during the Great Depression, just as it appealed to whites. (211)

In minstrelsy, this paradise of laughter and ease is, of course, racialized. A world of blackface is a world in which, by definition, everyone is black. For whites, this world is in part an object of ridicule. But it is also, as Taylor and Austen argue (and with their trip to Mardi Gras, perhaps demonstrate) an object of yearning. To put on blackface is, for whites, to be free, crazy, funny, authentic, cool. And this is also, Taylor and Austen suggest, what it means, or can mean, to put on blackface for blacks. Thus, Zora Neale Hurston, who loathed white minstrelsy but used minstrel tropes extensively in her work, often spoke admiringly about black primitivism, naturalness, and spontaneity. “[T]he white man thinks in a written language,” she said, “and the Negro thinks in hieroglyphics.” (269)

Hurston’s investment in black minstrelsy and black folk traditions inspired her to create Their Eyes Were Watching God, one of the great American novels of the twentieth century, built on her love of black people and black community. But her investment in minstrelsy also arguably inspired her to oppose integration, on the grounds that she didn’t want black primitivism and naturalness to be contaminated. Racial pride and racism for Hurston were two sides of the same mule bone.

Hurston’s habit of calling herself “your little pickaninny” in letters to a white benefactor is viscerally jarring. But her black minstrelsy is perhaps only a more exaggerated and painful form of a problem that confronts any minority cultural production within a racist society. Black music, theater, literature, entertainment, and comedy, from the days of black minstrelsy to the present, have been a glorious, seemingly limitless aesthetic treasure. But those riches have been created, and are in some sense dependent upon, the subcultural marginalization resulting from segregation and oppression. To celebrate black cultural achievement, whether Mardi Gras, or Hurston, or even Paul Robeson, is to celebrate in part the fruits of racism.

Nothing could make this clearer than black minstrelsy, a black art form built — with courage and cowardice, subversion and acquiescence — out of racism itself. Darkest America is, in this sense, not a story about an obscure and forgotten curiosity. Instead, it is a surprisingly graceful and erudite recuperation of what may be our most inspiring, most shameful, and most American art form.

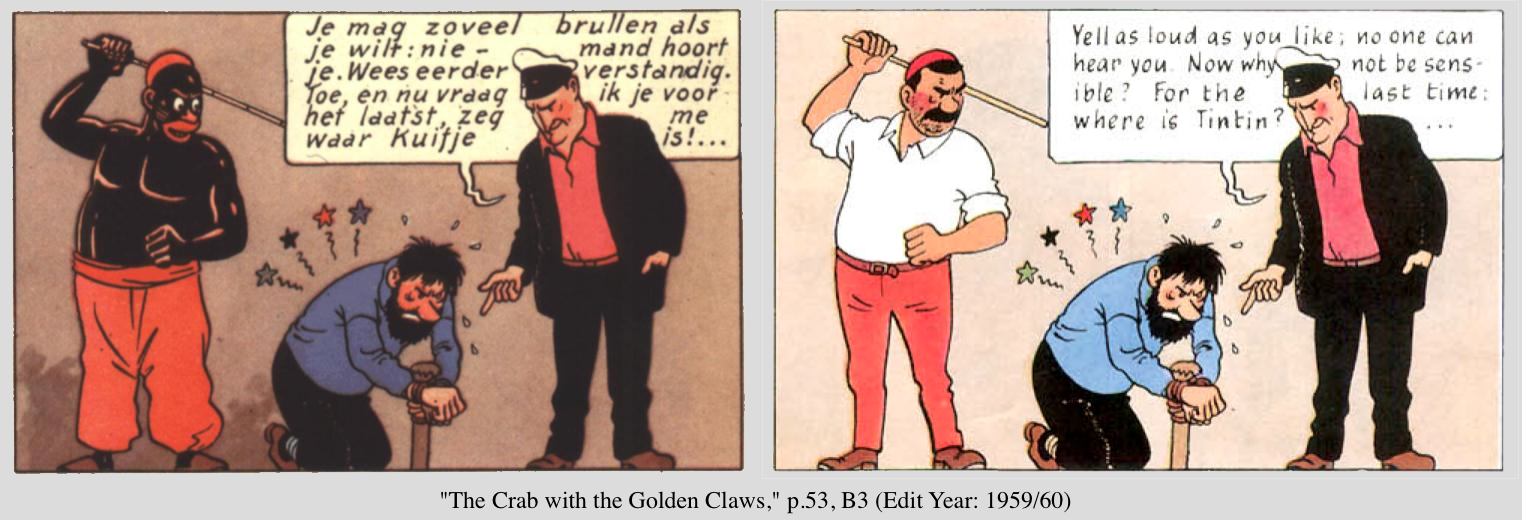

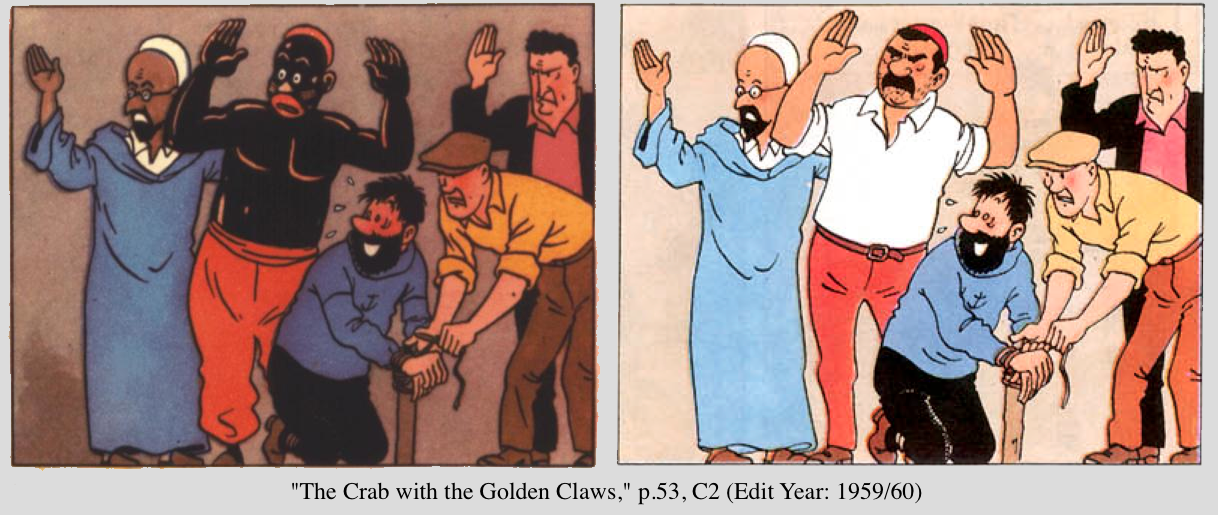

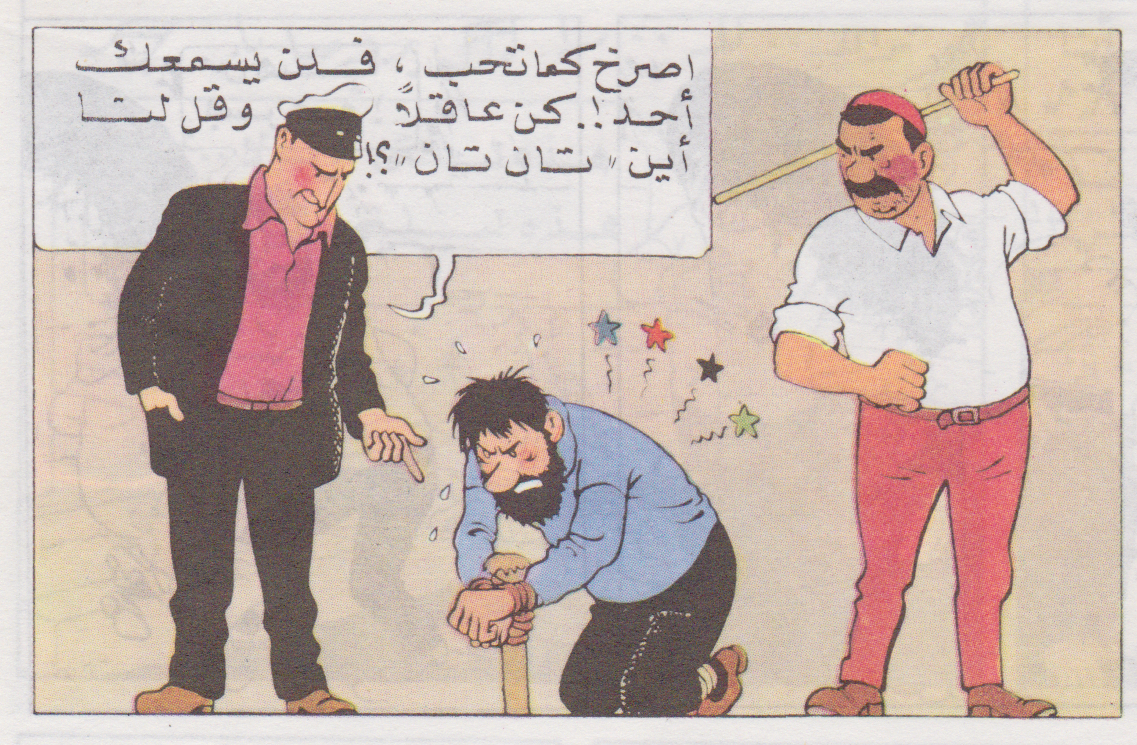

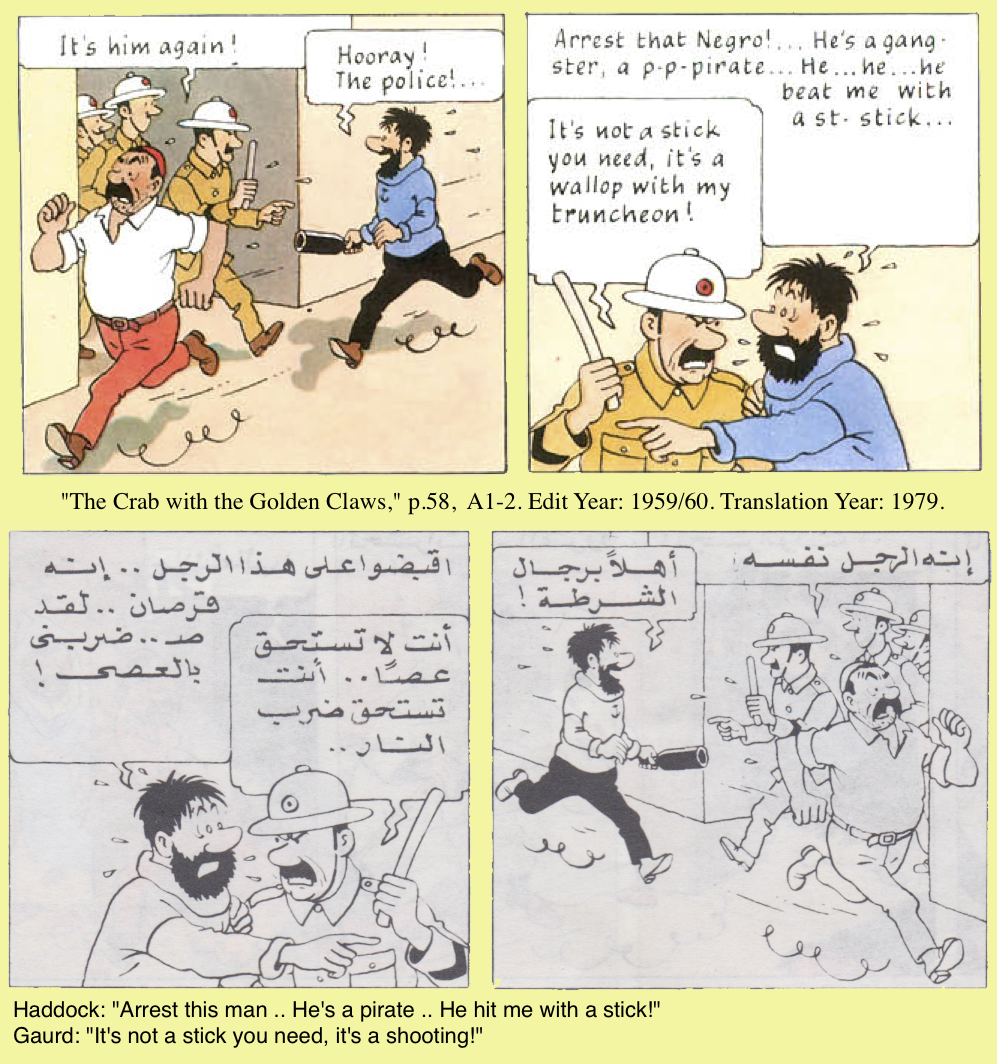

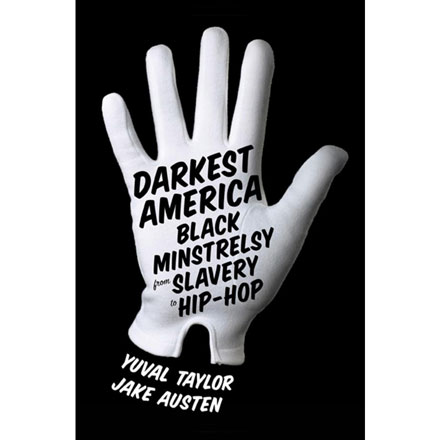

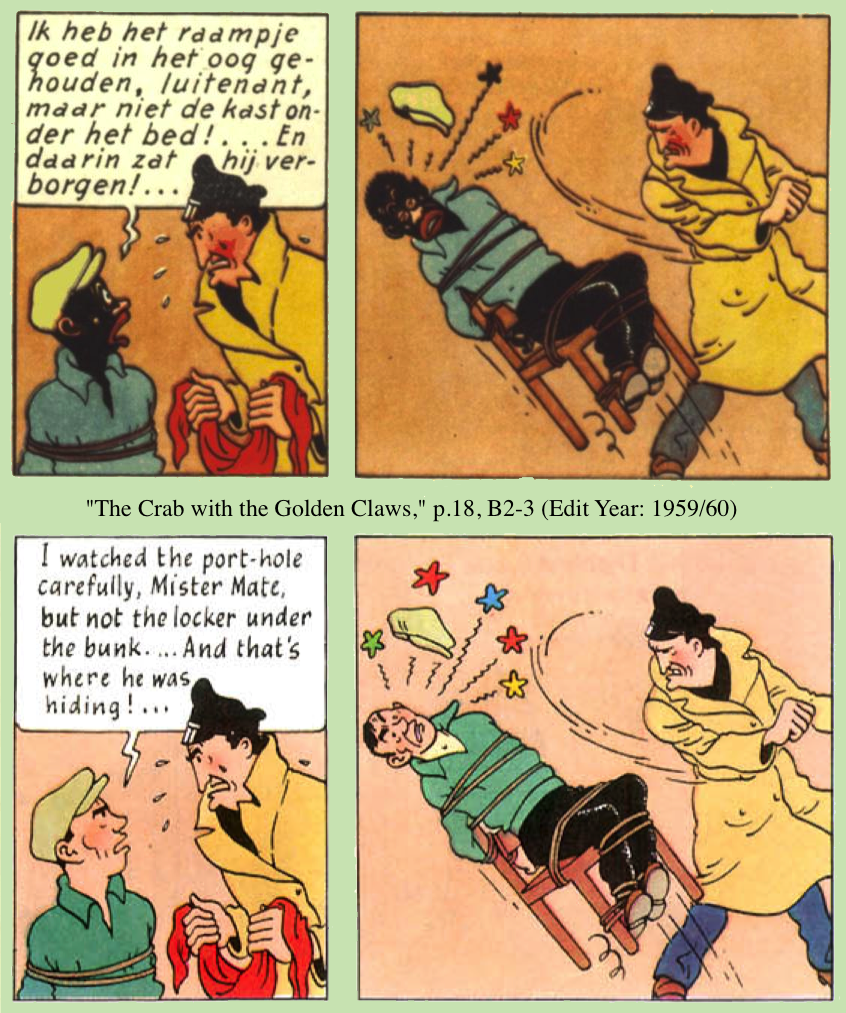

Deckhand “Jumbo” becomes markedly whiter.

Deckhand “Jumbo” becomes markedly whiter.