[Part One here.]

Wherever you look, you come face-to-face with the Other.

Other race, other religion, other sex, other age, other individual… you name it.

Reactions to the Other are complex and often self-contradictory: they run the gamut from instinctive loathing to fascinated attraction. The same person may be viciously hostile to, say, Indian immigrants, yet long to visit the Taj Mahal. (Excellent examples of this paradox are found in Edward Said’s book Orientalism.)

To deal with the Other, we can say that the best and most mature approach is empathy – fellow-feeling – as the common trope has it, putting yourself in another’s shoes. But there are far more common strategies: you can demonise the Other, as Hitler did to the Jews; you can ridicule him, categorise him, patronise him: in short, re-define him.

This range of responses is fully on display in Tintin ; perhaps more so than in any other popular entertainment of a like longevity. It’s telling, for instance, that (apart from the Bird brothers in The secret of the Unicorn), every single villain in the 23 albums is a foreigner.

To understand this, we can look at Tintin author Hergé’s life and career, and chart his evolution from rampant xenophobia to the empathy that emerges in his late works.

Georges Rémi—Hergé – was born in 1907 to a lower-middle class couple in Brussels, Belgium. He himself characterised his childhood as being ‘gray’, by which we may understand conventional and boring. He was a fervent Catholic.

Belgium harbors a culture that could pass for a caricature of normalcy and respectability, though not without its dark side. Hergé was comfortable in the most banal backwaters of this culture, never questioning its prejudices (something he looked back on, late in life, with a sort of rueful self-contempt.) He attended a Catholic school, and upon graduating age 18 went to work for a Catholic newspaper, Le Vingtième Siècle.

The brand of Catholicism that embraced him was deeply reactionary, royalist, violently anti-Communist, strongly anti-Capitalist (Moscow and Wall Street being seen as two sides of the same Judeo-Masonic coin ), unthinkingly imperialist. Hey, the Belgian Empire allowed the missionaries to convert all those benighted pagan Blacks.

The Vingtième was edited my a man who would have an immense and lifelong influence on Hergé, Father Norbert Wallez: an enemy of democracy which was seen as hopelessly corrupted by foreigners, Jews and Freemasons, an admirer of Mussolini.

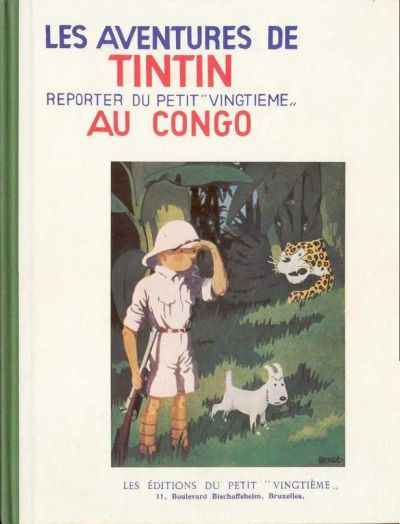

Wallez tasked young Hergé with creating a children’s supplement for the paper, called Le Petit Vingtième. And it was here that Tintin was born.

The first adventure was Tintin au pays des Soviets, a rollicking anti-Communist screed:

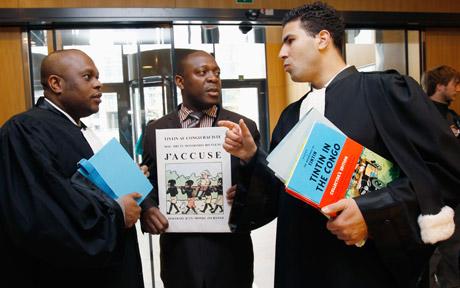

Next was the currently notorious Tintin au Congo.

When we think about the European colonial empires we remember those of Britain, France and Spain; in fact, even Denmark and Portugal had their colonies.

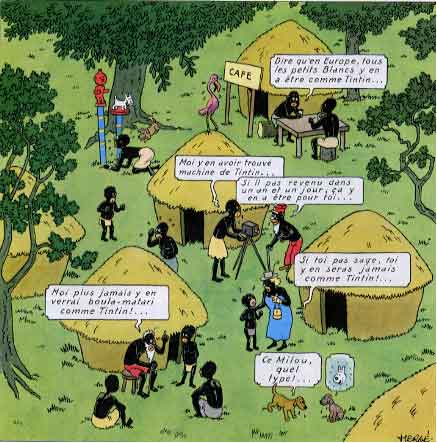

Little Belgium was dwarfed by its holdings in the Congo. It was infamous for the reign of atrocity inflicted on the Congolese by king Leopold II. You’d not think so reading young Hergé’s version: his Congo is a little paradise of merry, foolish darkies who love their benevolent Belgian overlords. (In 1946, though, Hergé had to tone down the imperialistic slant in his revision.)

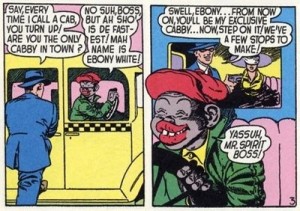

Then came Tintin in America, trotting out more stereotypes: a land of gangsters, greed-crazed businessmen, and tomahawk-toting Indians. (The latter, however, receive sympathy for their ill-treatment at the hands of despoiling Whites.)

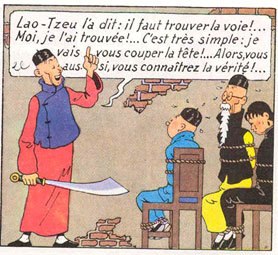

Then Cigars of the Pharoah, whizzing through Egypt and India (fakirs, snake-charmers, etc.)

“In reality” said Hergé, “my early works are books by a young Belgian filled with the prejudices and ideas of a Catholic […] they are not very intelligent, I know, and they do me no honor.”

Herge at work

But the next book would show the beginning of Hergé’s move away from mediocre stereotypes.

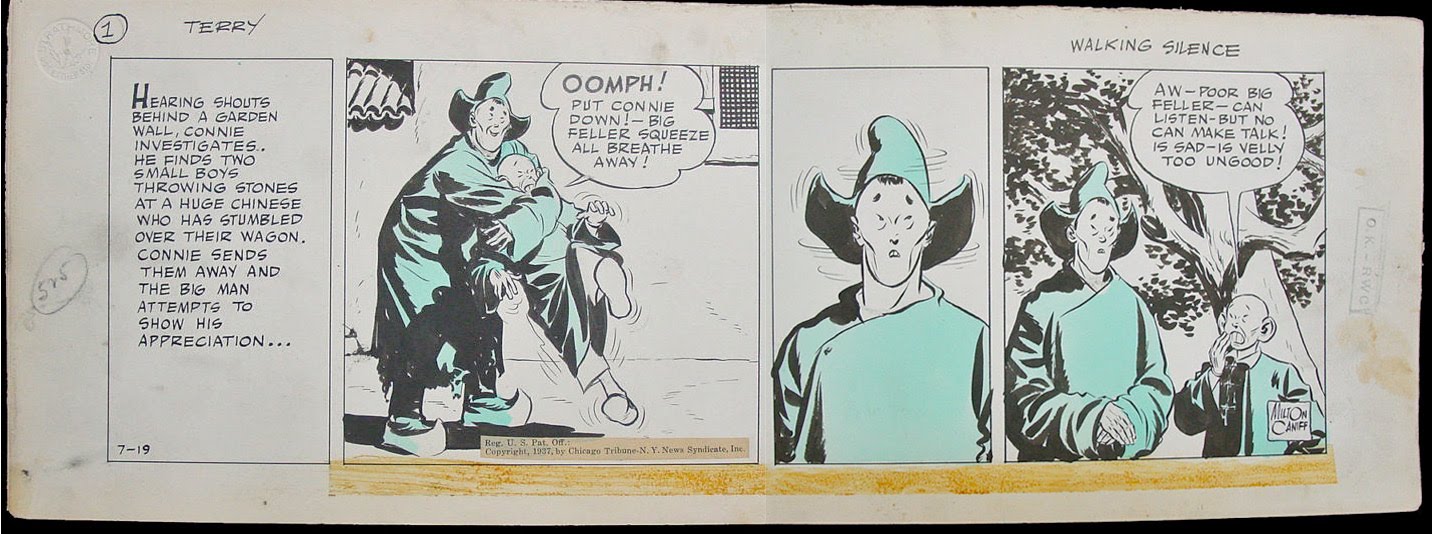

He had announced the next Tintin adventure would take place in China. A monk with knowledge of the country sent him a young Chinese art student: Chang Chong-Chen.

Chang had a profound influence on Hergé.

Here, for the first time in his life, the cartoonist met the Other he depicted, face-to-face. Chang exhorted Hergé to abandon his clichéd ideas of Chinese people and culture, to research seriously his subject. In return, Hergé put Chang into the strip:

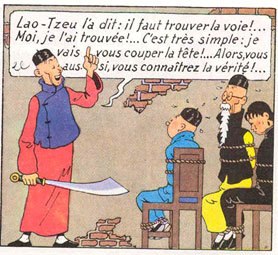

Here, remarkable for its time and context, Tintin and Chang share a good laugh over the stereotypes Europeans bear about the Chinese – stereotypes that would have been typical of Hergé, had Chang not come along:

click image to enlarge

click image to enlarge

This Shanghai street scene shows a new feel for realism:

click image to enlarge

click image to enlarge

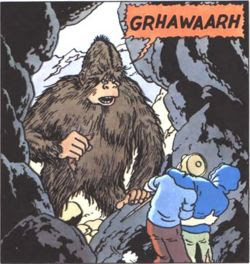

…but Hergè is not quite able to shake off the snares of cheap exoticism and cliché:

Hergé also seems, at this time, to be moving towards the political center, alarmed by Fascism and Nazism and Belgium’s own Rexism. Le Sceptre d’Ottokar depicts an idyllic Ruritanian-type kingdom threatened by a demagogue named Müsstler (Mussolini + Hitler).

But Belgium plunged into the cataclysm of World War II and German occupation, Le Vingtième Siècle disappeared, and Hergé began running Tintin in the ‘stolen’ collaborationist newspaper Le Soir. A move that would haunt him all his life.

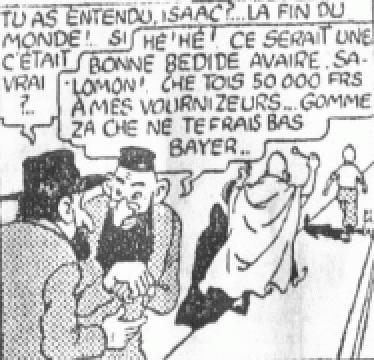

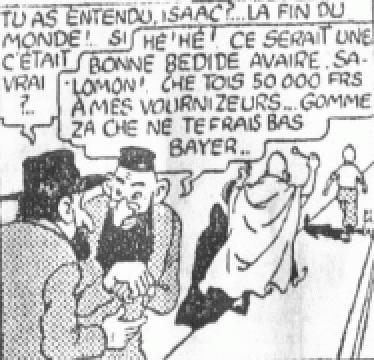

The first Tintin adventure under the occupation was L’Ile Mystérieuse. This is the work that would dog Hergé with accusations of anti-Semitism, and small wonder:

« You heard that, Isaac ? The end of the world !…What if it’s true?”

“Heh! Heh! It vould be good for business, Salomon! I owe 50 000 francs to my zuppliers… zis vay I von’t haff to pay…

That panel appeared only in Le Soir, and was excised from the 1942 album…for reasons of pacing, not of taste. (This was while the Jews of Belgium were being rounded up and sent to the camps by the thousand.)

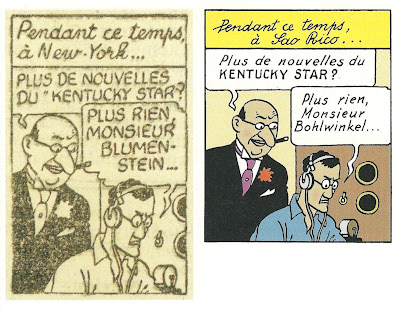

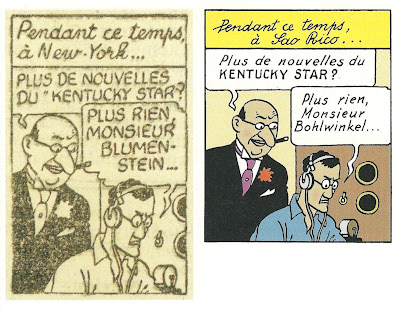

The plot concerns the race to get to an asteroid that has crashed into the Arctic. On one side is a European expedition, with Tintin & co along for the ride; on the other is the villainous American expedition, with no thought for anything but profit. It is bankrolled by a New York banker named Blumenstein. After the war, he was renamed Bohlwinkel and America became ‘Sao Rico’:

At left, the original, at right the postwar version

Top, nasty Yanks, bottom, nasty Sao Ricans

In 1969, Hergé would write:

“… you are a little too severe with me for this Blumenstein from the year 1940. I admit that I was wrong, but (and I hope that you will believe me) I was far from imagining that the Jewish stories that people told (and still tell today, like stories about people from Marseille, or the Scots […] would lead to such horrors.”

There’s more than a little cluelessness on display here, after Auschwitz. Hergé would always protest that “he didn’t know”, but was lucid enough to add:

“Perhaps I didn’t want to know”.

After the liberation of Belgium, Hergé was roundly reviled for propping up a collaborationist paper, and he was lucky to escape with his neck; as it was, he was banned for two years from any work in the press. It was this enforced idleness, and, no doubt, the need to put distance between him and his ultra-conservative views, that set him on the integral redaction of his albums – shovelling the dirt under the carpet, in the process.

Next: Approaching redemption.

All Tintin art copyright Studios Hergé/Moulinsart

_______________

The entire Tintin in Otherland is here.