This is part of a roundtable on The Best Band No One Has Ever Heard Of. The index to the roundtable is here.

_______

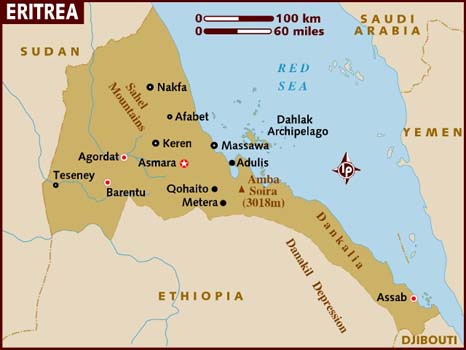

I come from a land in Africa bordering the Red Sea. Its name is Eritrea. There’s no reason for you to know it. I barely know it beyond its past. The country is one of the most informationally opaque in the world, governed by a regime convinced isolation and control trump vulnerability to invasion by land or Western politics. It took 100 years from that start of Italy’s reign to the end of Ethiopian occupation for my people to stand freely beneath their own flag. Twenty years later, they flee one of their own.

In North America, the music of my home remains largely unknown outside the diaspora.

While the fetishization of East African women in hip-hop has been extensively documented, references to Eritrea by popular bands have either had nothing to do with the country (Future of the Left’s “Arming Eritrea”) or ignored it altogether (Bright Eyes’ “Haile Selassie”). Lupe Fiasco’s latest track is also titled “Haile Selassie” and uses excerpts from the Emperor’s speech on inequality at the 1963 United Nations General Assembly:

“That until the philosophy which holds one race superior and another inferior is finally and permanently discredited and abandoned; That until there are no longer first-class and second-class citizens of any nation…[Until that day, the African continent will not know peace.]”

If these words seem familiar, the same excerpt was featured in Bob Marley’s “War.” The General Assembly address occurred less than a year after Jamaica’s independence; the General Assembly address occurred less than a year after Haile Selassie annexed Eritrea and declared it the 14th province of Ethiopia, leading to a war for independence spanning 30 years.

Another of the excerpts in Fiasco’s “Haile Selassie” involves the act of silencing:

“Throughout history, it has been the inaction of those who could have acted, the indifference of those who should have known better, the silence of the voice of justice when it mattered most, that has made it possible for evil to triumph.”

There are many ways to destroy a cultural identity. Forbidding access to a language is one of them. The year 1962 was also the year Haile Selassie burned all books in Eritrea written in the country’s most widely spoken tongue, Tigrinya, and decreed all new books and educational materials would be printed solely in Amharic, the national language of Ethiopia. The role of Eritrean music, for decades already a call to arms against occupiers, skyrocketed in significance.

In terms of global distribution, this music has at best been lumped in with the synthesizer-averse E?thiopiques series. Emulations of Eritrean music have also appeared stateside by well-meaning bands (e.g., Fool’s Gold’s “Yam Lo Mosech“). Yet, the Eritrean heroes responsible for inspiring large swaths of the country to fight for independence — singers who were jailed and tortured as political dissenters — have seen limited exposure beyond their borders.

The reasons are numerous. To Western ears, Eritrean music has about as much rhythmic variation as mud; the same drumbeat can be heard at roughly the same tempo on the majority of songs; the length of each song typically falls between 6-9 minutes: Pop music this is not. And truly, these songs are for dancing, which in certain Eritrean traditions entails shuffling in a circle while shrugging one’s shoulders to the beat.

Listen, I know. I know how this sounds. I expect no miracles from new listeners. It took decades for me to embrace it. The voices were shrill. The singers’ frequent inability to commit to one pitch per vowel an affront to whatever thread of Puritanism I inherited from America. The meandering saxophone — an aural figure so revered it was employed during a minute of silence when Eritrean President Isaias Afewerki held a gathering in New York City in 2011 — haunting more songs than I care to admit.

Historically, ours has been a music of metaphor and self-censorship. For more than half a century, Eritreans have been singing about their presumably-human-and-definitely- DEFINITELY-nothing-at-all-to-do-with-political-independence loves because they couldn’t sing openly about their own country. Some tried; eyes were lost. And yes, occasionally the lyrics were about romance, but mostly they were about the endless pursuit of freedom.

Below are a handful of songs/videos featuring Eritrean performers. Some highlight the kraar, a stringed instrument present in many Eritrean songs. By no means is this a comprehensive list. While the Tigrinya tribe of Eritrea is its biggest, there are eight other ethnic groups in the country, each with its own language, style of dance, and festive garb. Additional songs and artists can be discovered on Eritrea 24, Spotify, and other online primers.