Lily James, the latest actress to embody Cinderella, declared the character “almost a superhero.” NPR’s Linda Holmes reversed the comparison: “Is Captain America a Cinderella story?” Holmes likened Cinderella’s pumpkin coach to the Batmobile, concluding that if the core of Cinderella is “just a rescue of a deserving underdog from an ordinary life and delivery to an extraordinary one,” then most superheroes belong in the combat equivalent of glass slippers.

It’s a fair point, but I think Holmes misses Cinderella’s most memorable qualities. Literally the most memorable, the ones researchers have proven are most memorable in psychological studies. Turning mice into coachmen and rags into ballgowns–apparently that’s the kind of magic our brains are wired for.

To explain why, we need to visit Cinderella’s home planet:

“I was sent as a diplomat to the planet Ralyks. Because the decision was very sudden and I didn’t have a lot of time to research Ralyks, I decided to take a visit to Ralyks’ equivalent of the Smithsonian — a large network of museums and zoos intended to provide a representative sampling of all of the different kinds of things of this world.”

That, believe it or not, is the first paragraph of a psychological experiment testing what kinds of ideas are easiest to remember and so retell. The researchers, Justin Barrett and Melanie Nyhof, sent 54 ambassadors to Ralyks in 2001. They all returned safely, but not their recall of the Ralyks Smithsonian.

The ambassadors (all college students ages 16 to 25, which, in my opinion, is recklessly young for intergalactic diplomacy) tended to forget the ordinary exhibits. Like the “being that is easy to see under normal lighting conditions” or the being that “consumes and metabolizes caloric materials to sustain itself.” They did better with the bizarre or unusual, like the being that “just does things randomly” or the one that “could make out the letters on a page in a book if it is as much as 50 feet away, provided the line of sight is not obstructed.”

But they were best with beings that possessed a feature that violated some intuitive assumption but still satisfied the majority of other expectations. Barrett and Nyof call these expectation-bending beings “minimally counterintuitive.”

I call them superheroes.

“I came to an exhibit about a being that is able to pass through solid objects.” So that would be either Vision from the Avengers or Shadowcat from the X-Men, right?

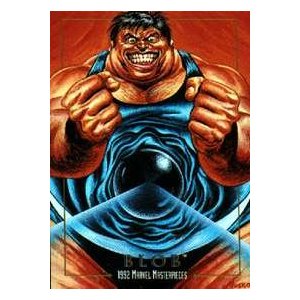

And, speaking of mutants, here’s the Blob and/or the Juggernaut: “To the south of this room was one containing a being about the size of a young human that is impossible to move by any means.”

And don’t forget Wolverine’s healing powers: “The second room illustrated a being that will never die of natural causes and cannot be killed. No matter what physical damage is inflicted it will survive and repair itself.”

Probably not everyone will remember Multiple Man: “The next room I came to featured a being that can be completely in more than one place at a time. All of it can be in two or all four different corners of the room at the same time.

Multiple Man premiered in Fantastic Four, same as the Watcher: “a being that can remember an unlimited number of events or pieces of information. For example, it could tell you in precise detail, everything it had witnessed in the past…”

And let’s not leave out the mightiest mutant of them all, Professor X: “a being that can pay attention to any number of things all at the same time. For example, if ten people or ten billion people were talking to it at the same time, it would be able to keep track of what all of them were saying.” (Okay, the Professor might need the assistance of his mind-expanding computer Cerebro, but close enough.)

Lest you think Melanie and Justin only read Marvel as kids, they included certain Kryptonian superpowers too: “a being that can see or hear things no matter where they are. For example, it could make out the letters on a page in a book hundreds of miles away and the line of sight is completely obstructed.”

So all of Ralyks’ counterintuitive specimens would be at home in a comic book. I could argue that the supervillain the Collector secretly originates from the planet Ralyks, but let’s take this in a slightly different direction.

I hunted down Barrett and Nyhof’s study (“Spreading Non-natural Concepts: The Role of Intuitive Conceptual Structures in Memory and Transmission of Cultural Materials”) from a reference in Alex Mesoudi’s Cultural Evolution. (Ever play a game of scavenger hunt where each found item is a clue to find the next? Academics call that “research.”) Mesoudi wants to know how and why some ideas get passed on and others die out. Why, for instance, Cinderella remains so popular, while the vast majority of Grimm’s fairy tales have been utterly forgotten.

Barrett and Nyhof think we’re biased for the minimally counterintuitive. Basically we’re Goldilocks. Too much (“a jealous Frisbee,” suggests Mesoudi, “that turns into a caterpillar every other Thursday”) and our brains get burnt with ungraspable weirdness. Too little and our lukewarm neurons die of boredom. We, like Goldilocks, prefer Baby Bear’s “cognitive optimum,” that just-right balance between “satisfying ontologically driven intuitive expectations” (Mama Bear) and “violating enough of them to become salient” (Papa Bear).

Mesoudi looks at culture in Darwinistic terms, which makes those Ralyks specimens well-adapted mutants. They’re the fittest. They’re built to survive. Five of the six most frequently remembered specimens were counterintuitive. Common ideas died out fastest, and the “merely bizarre” had a tendency to mutate into the counterintuitive, thus increasing their survival rates too.

This, according to Barrett and Nyhof, could help explain not only Cinderella’s godmother, but religion too: “it is these counterintuitive properties that make religious concepts salient. Increased salience, in turn, enhances the likelihood that the concept will be remembered and passed on.” They cite examples from “religious systems and folk tales from around the world,” including stories about “people with superhuman powers.”

But when Barrett and Nygof invented their Ralyks Smithsonian to measure concept recall, they didn’t seem to know they were reproducing superhero character types (AKA “people with superhuman powers”). Which makes Barrett and Nyhof unknowing participants in a larger cultural evolution study. Their invented specimens are either examples of parallel evolution (meaning they dreamt up Superman’s X-ray vision and super-vision independently of his culturally pervasive character), or, more likely, Barrett and Nyhof absorbed their superpowers through cultural exposure and reproduced them unconsciously.

Either way, superheroes are especially fit cultural survivors. The character type may be a mostly 20th century American mutation, but one that satisfies something much deeper in the human psyche. The call of the weird-but-not-too weird. Superheroes occupy that sweet spot. Its part of their definition. According to scholars Hal Blythe and Charlie Sweet, an effective superhero must have superpowers, but those “powers are limited” and the character “human,” balancing the counterintuitive with the ordinary. Even the alter egos tends to be “an adult, white male who holds a white-collar job,” which to a white male white-collar reader is as ordinary as you get.

Maybe their Smithsonian didn’t include any category-bending specimens because the students placed them all into the pre-existing category of “superhero.” In which case, Melanie and Justin might want to schedule a return trip soon. I’ve never visited myself, but from the diplomatic dispatches it sounds like a planet well worth visiting:

“I left the building and went to my new office to ponder all of the things that can be found on Ralyks.”