I’ve been having a debate with Charles Reece and Mike Hunter over the misogyny, or lack thereof, in Raymond Chandler’s work. I thought I’d highlight one of my comments here for those who are interested:

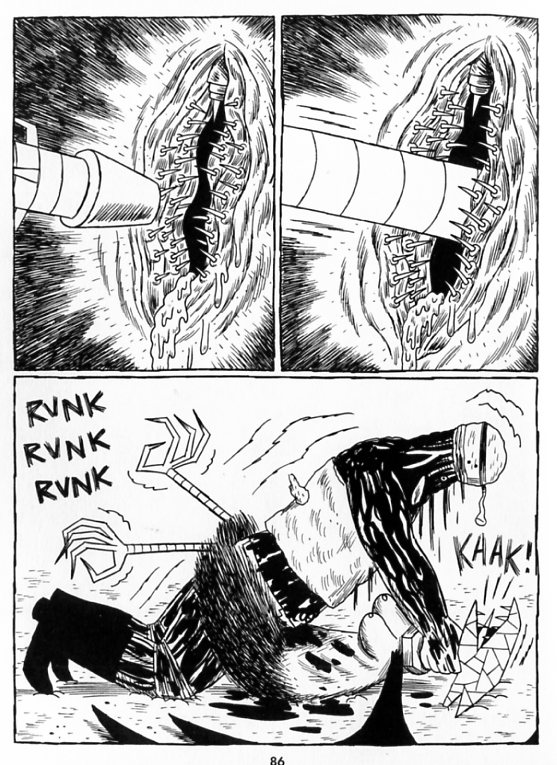

I’m not using misogyny casually or dismissively. [The Big Sleep] is powered by disgust, and disgust and corruption are insistently associated with femininity. The most powerful image of the book is the mad Sternwood daughter, a vision of sexualized, feminized chaos from which the male soldiers recoil.

Again, the argument that men are killed and men are bad seems to really pretty much completely miss the point. Masculinity is absolutely an incredibly important issue in the novel — who is a man, who isn’t, what honorable men are like, how men keep themselves pure. You and Mike seem to have this idea that there you figure out misogyny by looking at the relative fates of the men and women in the book. But that’s silliness. The issue is that femininity is a corrupting influence — which affects men too. As Coates says, masculinity is built on a rejection of weakness which is nonetheless central to masculinity. Even the male body becomes feminized, because all bodies are feminized (so that, for example, the old man’s decadence, with all the hothouse flowers, is thematically linked to the way he’s living with his two united daughters…even old age becomes feminine.)

Misogyny is absolutely an ideology/passion which destroys men, and indeed promotes hatred of men (whether homosexuals, or the elderly, or anyone who doesn’t measure up to being a man, which is everyone.) One of the great things about Chandler’s novel is the way it demonstrates this so clearly and with such passion. It’s uncomfortable and probably evil, but the way it works through the permutations, and the vividness of its loathing for women and ultimately for itself, is fascinating and I think valuable. I like the Thin Man quite a bit, strong female character and lack of misogyny and all, but it doesn’t have anything like that insight or passion.

I think in part the issue is that you and Mike are only seeing misogyny as applying to female bodies? Misogyny is very frequently directed at female bodies…but it’s also, and very much, directed at femininity, which can be associated with female bodies, but which is also a trope which can be seen everywhere, in female bodies, male bodies, or decadence generally. The Big Sleep is actually a perfect example of how this works; the misogyny pervades the entire book, creating a world of corruption, decadence, perversion, and disorder, within which honorable men struggle for cleanness and honor and masculinity.

This has gotten me thinking a little bit too about why feminism is important for men. Not sure where or if I’ll write that up, but I think it’s worth thinking about — and I think Chandler is a useful way of getting at it.