The discussion fostered by cartoonist Eddie Campbell’s essay on comics and how they work, entitled “The Literaries,” published last month at TCJ.com, has been alternately fascinating and frustrating. Characteristically for the comics community, blogosphere reactions were divided roughly into two camps: fanboys cheering him for tracing a line in the sand against the naysayers who would hold comics to higher standards, and those same naysayers, saying, well, nay to the most superficial parts of his piece without noticing the beam in their own eye.

Campbell’s polemic was voiced in part against Ng Suat Tong’s touchstone essay “EC Comics and the Chimera of Memory” published in The Comics Journal in 2003, and recently republished here. At the time, the essay was a brilliant corrective to fanboy orthodoxy, helping usher in a more mature approach to comics criticism that refused to isolate comics from the wider cultural field, but rather attempted to judge an acknowledged comics classic by the yardstick of major achievements in other media. Unsurprisingly, the work of Kurtzman, Feldstein, Craig, Krigstein, Wood, Ingels, Williamson, Davis, Elder, et. al. seemed less than great when compared to Aristophanes, Anne Frank, Goya, Giotto, Citizen Kane, Van Gogh, The Romance of Three Kingdoms, Catch-22, and La Grande Illusion.

Suat’s essay, which followed in the tradition staked out by Gary Groth at The Comics Journal through the previous decade-and-half, was a highly illuminating exercise, and a prophetic one in that a large part of serious comics criticism since then has been preoccupied to the point of obsession with making similar comparisons. For obvious historical reasons, comics aficionados have been affected by status anxiety since at least Gilbert Seldes, and comics fandom has been plagued by it to the point of insularity. And the particular tendency at play here has been on the rise in the last decade as comics have experienced increased cultural and institutional acceptance.

Let us leave the fanboys aside and concentrate on the critics. I will forego discussing Suat’s querulous and ungenerous riposte, which only does his original piece disservice and focus on Robert Stanley Martin’s trenchant critique instead. Denying Campbell almost the entirety of his argument, Robert insists that he and others writing from similar perspectives do indeed take comics seriously as a visual medium, calling Campbell’s assertion of a literary bias a “straw man.” He further unapologetically insists upon focusing primarily on story in any comic that tells one, taking into consideration visuals only “as a means to an end which happens to be that story’s realization.” In Robert’s caricature of Campbell, the latter considers story “irrelevant”, preferring to focus instead on details of design, execution, or detail—on “flash.” He understandably asserts that this straw man (sorry Robert, but it is what it is) should not “be taken the least bit seriously.”

OK, Campbell’s piece is not rigorously argued and one can point to inconsistencies, but Robert nevertheless seems to be missing the point. Campbell does not dismiss ‘story’ (as I will forthwith call it, for reasons about to become clear) as an integral element to comics, but rather extends the concept of story to the images themselves:

…the art is to be found in the story the cartoonist tells in his graphic strokes, his deployment of the whole panoply of cartoon effects and ways of seeing and representing. In the work of an exceptional artist there can be a whole other story happening.

Campbell’s point is not just basic to criticism of visual art, but also reflects a perspective so commonplace that it has become a truism, namely that the value of a story lies as much in how it is told as what it tells. Leaving aside the problematic discussion of form and content and the eagerness with which many comics critics want to separate them, this is at the crux of Campbell’s argument and is exemplified well in his Billie Holiday analogy: it is her performance of a song like “Who Wants Love”, rather than the words themselves that make it a great song when she sings it.

In his response to Campbell, Noah Berlatsky seems to agree with this basic premise, but uses that song as an example of how Campbell is so overeager to separate comics from literature that he overlooks the ways in which her performance is precisely that. This is not a discussion I want to engage at length here—Robert and Noah are clearly right that comics can be seen as a form of literature, and especially that attempting to segregate the form leads to insularity, but I do not see how such an endeavor is implied by Campbell’s argument. He merely warns against insisting too assiduously that comics be measured against, and according to the logic of, whatever standard one might posit from a wider cultural field. If you ask for The Romance of Three Kingdoms when reading Two-Fisted Tales you are bound to be disappointed, as Suat rightly pointed out in his original piece, but more importantly you are liable to miss out on whatever genuine artistic value is offered by Kurtzman and his collaborators, whether their efforts compare favorably to those of Luo Guanzhong in the final tally or not.

A great work of literature, or other work of art, might be a fine aesthetic ideal to keep in mind when criticizing comics, but formally and conceptually it can blinker you to how comics work if you insist on its priority. Of course you can compare comics with works in other media, but hopefully we can all agree that they work in the distinct ways and in the distinct tradition that make them comics, and that paying attention to these help us understand and appreciate them better than if we apply the logic of a different art form to them more or less wholesale. Campbell oversells his argument when he calls comparisons with other media ‘irrelevant criteria’, but his basic point—that we should try paying closer attention to how comics work and what they do—is a good one.

But is it one we need to be reminded of? As we have seen, Robert insists that Campbell’s identification of a literary bias is wrong, but is it? Let us take a look at Suat’s EC piece: in more than 5,000 words discussing plot, character, theme, and ideology—i.e. ‘story’—comments on the visuals of the EC comics are relegated to a few laudatory adjectives. They never really become part of the argument, even as they pertain to ‘story’ elements. More confusingly, Suat argues in one place (discussing Krigstein and Feldstein’s “Master Race”) that form and content can and should be separated: “a feeble story, no matter how masterfully executed, should not be excused on the basis of mere thematic maturity”, but almost immediately follows this by saying it can not: “style and content cannot be divorced in what is clearly a narrative story.” Which one is it?

Or we could look at Robert’s extended body of comics reviews. One understands why he so emphatically describes the visual aspects of comics as “means to an end.” While perceptive and often expansive when it comes to the ‘story’ aspects of the comics, he generally relegates visuals to a few, adjective-laden sentences, good on declaration but less on explanation or analysis. His critique of E. C. Segar is particularly telling: Popeye’s high points for him are the anomalous moments of satire in certain stories, which as I have discussed elsewhere seems to me a perfect illustration of how evaluating cartooning by its literary ‘content’ may blind one to its more obvious qualities—in Segar’s case the kinetic humor, absurdist wit, and visual originality of his cartooning.

Noah, for his part, is less wedded to high culture frameworks of evaluation. Nevertheless, his response to Campbell carries intimations of the literary bias at issue here. Despite his attentive visual analysis, his final take on the Kirby-Lee Captain America page is a classic example of reading rather than looking. To him, the page is a self-reflexive performance by the authors—its anti-literary turn a celebration of Kirby’s ‘Ab-Ex’ flexing of drawing chops. Where does Noah get this idea? Well, the obvious place would be the caption at the top of the page, written by Lee, which presents it as such.

This is a misunderstanding of Kirby’s work. Reading the story in question attentively, or really reading any of the prime sixties Marvel material, it should be clear that there is a tension between image and text, a tension that precisely has to do with Kirby and Lee’s working method, as Campbell also notes. Lee is indeed a self-reflexive writer who is all about performance (sometimes delightfully so), but such terms hardly describe Kirby’s artistic sensibility. Invariably earnest, he was never a showoff and the Campbellian story he tells, beyond the ‘story’ of Captain America versus Batroc, is one of pain and perseverance, of the human condition. Literary or not, it is a story very much at odds with Lee’s writing and one that reveals itself only if one pays attention to his cartooning instead of reading its labeling.

Similarly revealing is Noah’s analysis of Holiday’s performance of “Who Needs Love.” He describes it as great because of her ironic distance to the banal lyrics, which enables her to imbue them with greater meaning that their hack writer ever imagined. This might be right in a sense, but the process seems to me much simpler: Holiday recognizes that clichés contain truth and is able to bring out this truth in a performance that is necessarily unironic. The anxiety of academically schooled critics around cliché tends to lead them into contorted and unnecessary arguments such as Noah’s when faced with it. This seems to a major reason why those products of popular culture that have genuine aesthetic value—in casu certain comics—tend to fare badly when subjected to the kind of scrutiny taught at the academy. In this context Campbell’s fairly straightforward point is worth listening to.

But how can one deny the precedence of more straightforwardly literary ‘story’ told in these comics, as Campbell is accused of doing here? And should one do so? Not necessarily, but on the other hand I see no reason to give it absolute priority. The ‘story’ is obviously an important part of the vast majority of comics and critical engagement with it can yield important insights, as it indeed often does in the writings of Suat, Robert, and Noah. My problem with the discourse as presented, however, is with the apparent—and in Robert’s case outright—denial that other approaches might be equally fruitful. That the drawings are always a means to an end, that the non-literary parts of these comics are outweighed in importance by the literary ones.

This appears generally to be less of a problem with criticism of comics of obvious literary ambition, such as those by Campbell himself,* and more with traditional genre comics. The context of these works is mass culture and as such tends toward the sub-literary. There is no question that a lot of this material is disposable, but fastidious comparison with works predominantly understood in terms of high art seems to me a blunt instrument remarkably unsuited to understanding what qualities some of it might possess. It also encourages a bizarre hierarchy of comics genres in which an unobjectionably well-crafted comic created in a high literary context, such as Fun Home, is automatically better than one created to entertain young readers, such as Astérix. Where Persepolis by its very conception is superior to Polly and Her Pals. A prescriptive and unenlightening view of art stuck in the elitist framework of high modernism. It has long since been shown how dogmatically elitist approaches to genre literature are problematic, so there is little reason to import them directly into comics criticism.

Ultimately modernist elitism is unable to explain why certain comics (or works in other media) telling simplistic ‘stories’ and offering cheap thrills endure while most others do not, in any way other than by referring to their level of craft or (*shudder*) their pandering. Some might find this adequate, and it is doubtless true in many cases, but it still fails to explain adequately why certain comics despite their flimsy premise present so powerful, original, and enduring a vision.

Robert very perceptively associates efforts to identify such qualities in genre comics with auteur theory. His take on it is negative, and auteur theory has of course been deconstructed as often happens to theories without strict methodologies, but it might yet prove useful in the present context. It seems to me that Robert’s characterization of at least its American iteration is biased and reductive: if the ideal indeed was to eschew ‘story’ at all costs, its usefulness would obviously be limited. I am willing to be corrected, but that is not how auteur theory was taught to me. In any case, it seems to me absurd to suggest that the filmmakers championed by the French auteur critics—from Vigo and Renoir to Hawks and Hitchcock—worked to subvert their screenplays, as Robert suggests. The majority of them were expert storytellers.

As I understand it, auteur theory rather emphasizes how a sufficiently original or otherwise powerful creative vision inexorably emerges in any work that the creator is involved in, regardless of the constraints, commercial or otherwise, under which it is created. Such a perspective seems to me eminently suited to comics, perhaps even more so than to film because comics are created by fewer people, often a single person. Of course there is the danger of lazy criticism of the kind Robert berates, where Jack Kirby is compared to Homer, but such dangers abound with every method.

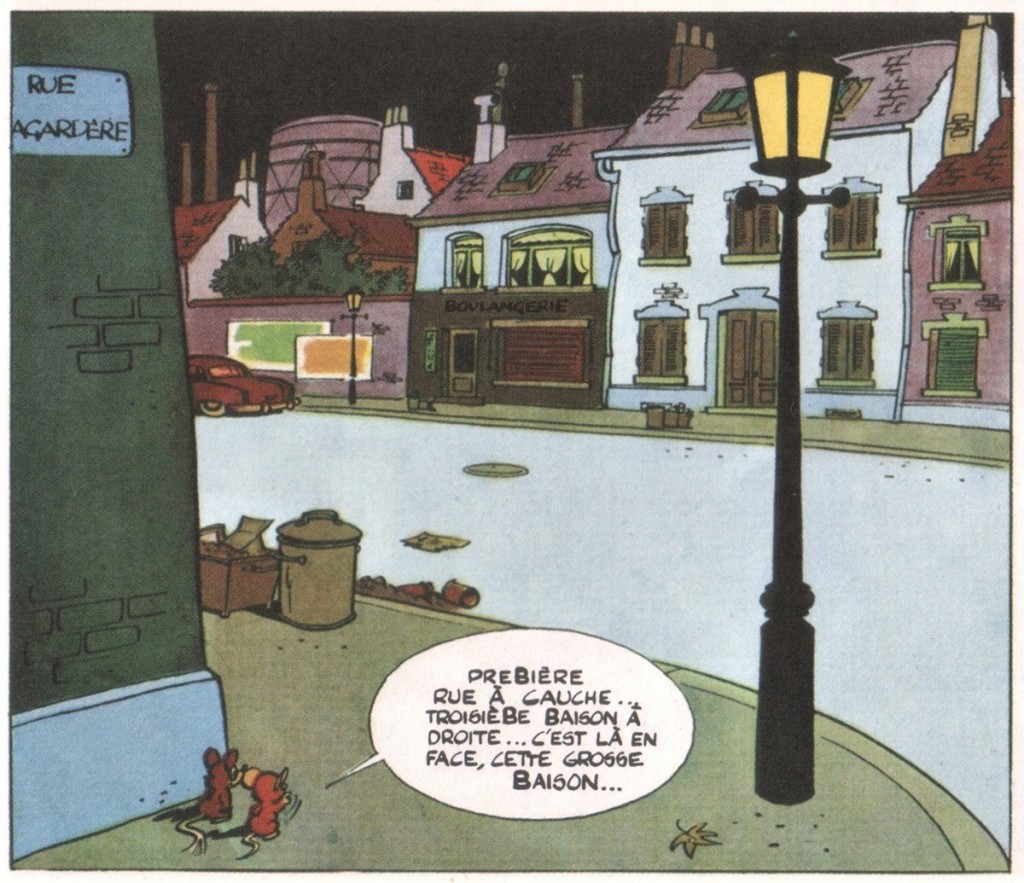

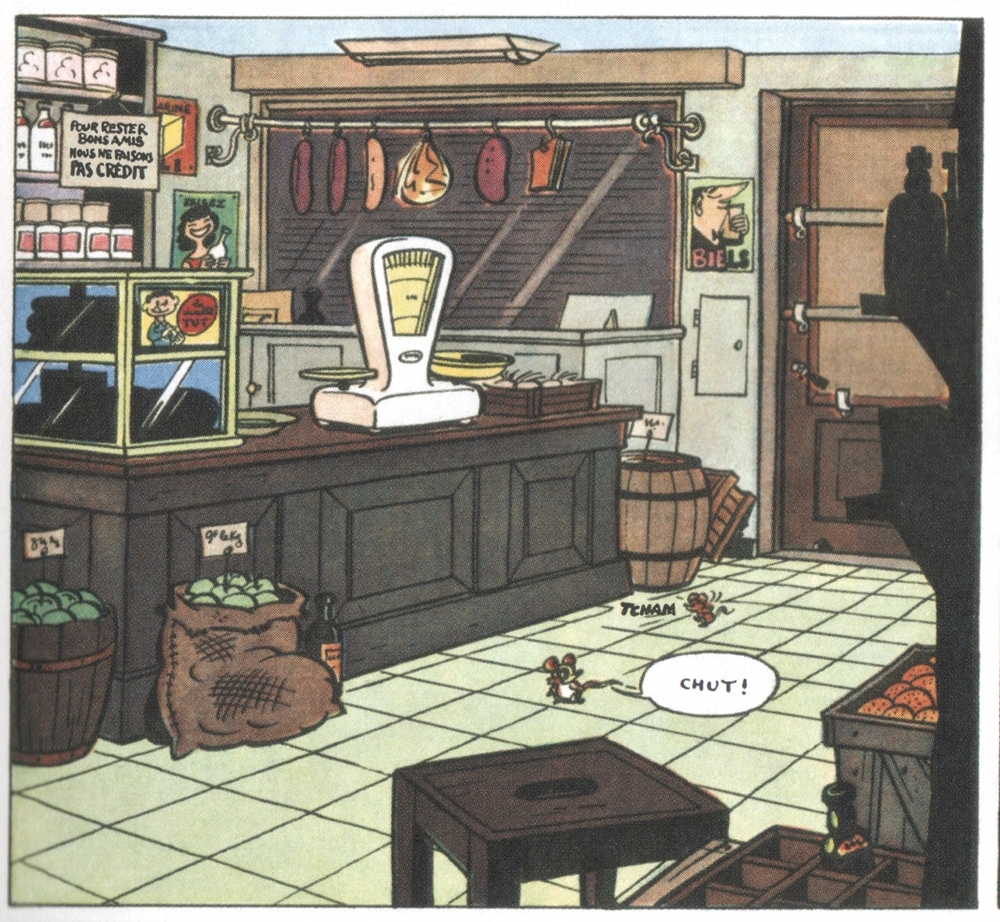

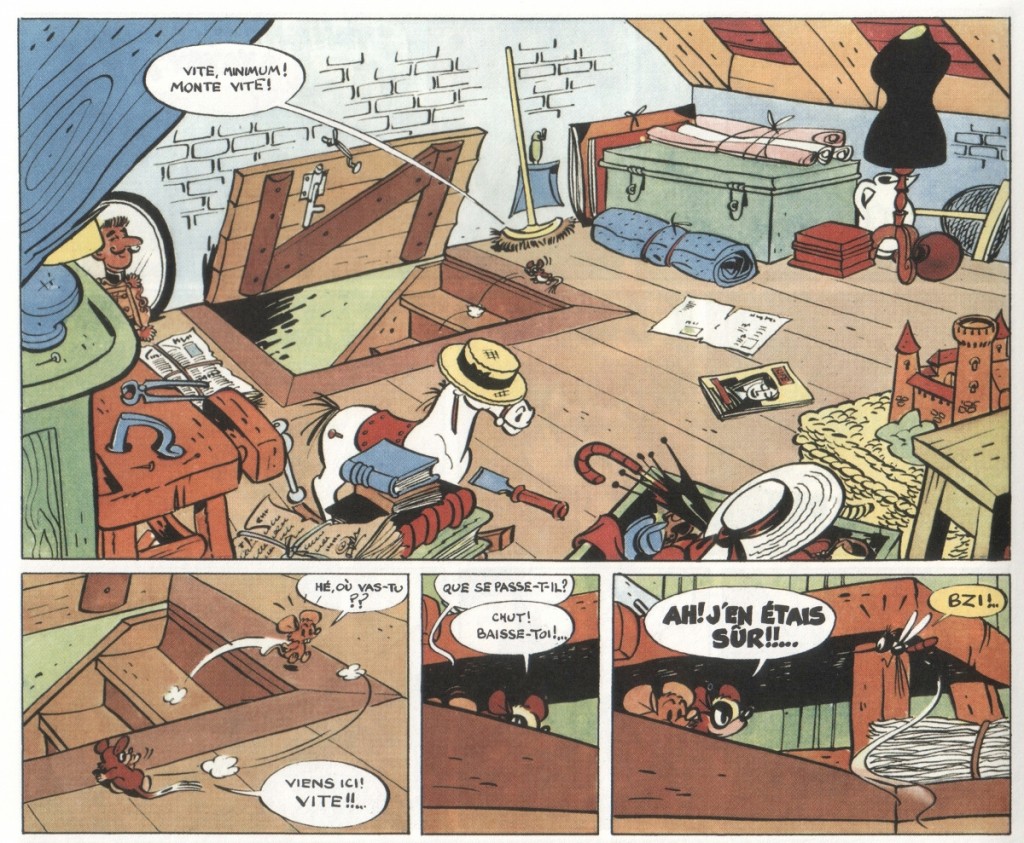

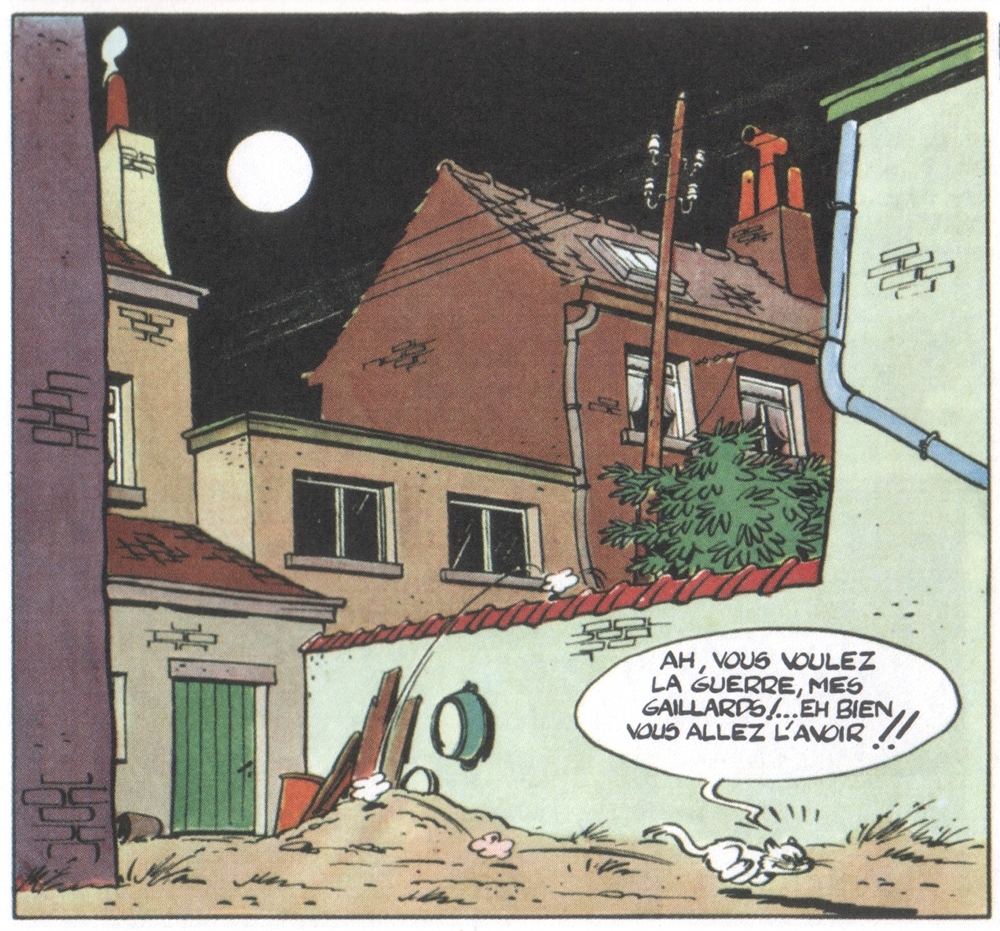

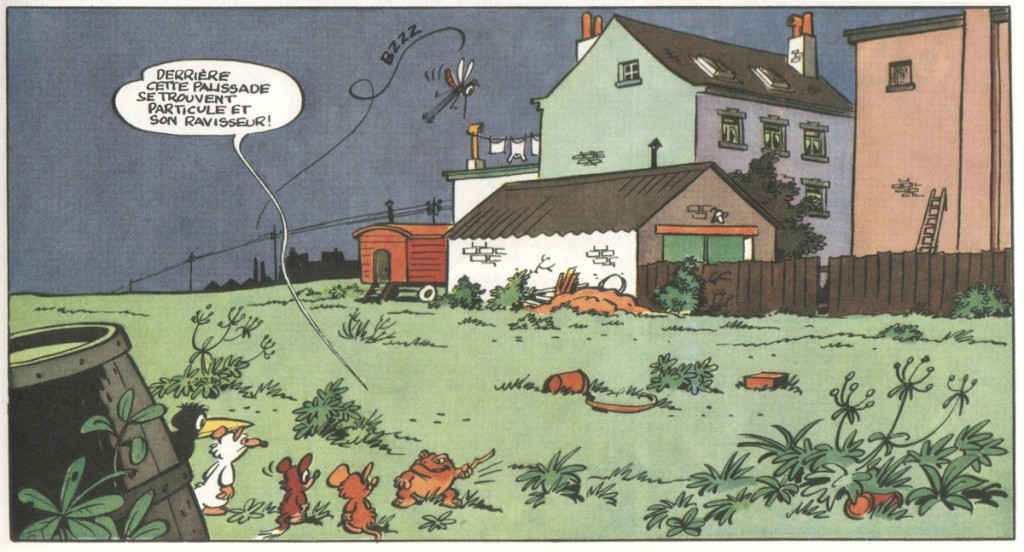

I realize now that I was probably working on principles akin to auteur theory in my attempts on this site to explain why I find Tintin and Popeye to be fascinating works of art. But let me offer another example, and get to the images you have been looking at while reading. As this whole ‘literaries’ debacle was unfolding last month, I was reading for the first time since childhood Raymond Macherot’s third Chlorophylle story, Pas de Salami pour Célimène (‘No Salami for Célimène’, 1955). For those unfamiliar with it, Chlorophylle was a funny animal series aimed at kids originally published in Le Journal de Tintin. Basically an adventure series, it situates its protagonists, the Dormouse Chlorophylle and his friend Minimum (whom I suppose is a field vole), in scenarios fraught with danger and mystery. Macherot was an environmentalist before the fact and all-round progressive who incorporated into his comics elements of social and political satire, but he generally kept things fairly simple, if always entertaining.

Where the first two Chlorophylle books take place in the countryside and feature the struggle by a ragtag group of small animals against an incursion of rats—a clear parallel to the Nazis—Pas de Salami substitutes an urban setting to tell what is basically a detective story. Chlorophylle and Minimum are Holmes and Watson investigating the disappearance of salami from the local butcher shop, as well as the connected disappearance of a mouse child. Their primary antagonist is a femme fatale-type cat, the Célimène of the title (appropriately named after the elusive love interest of Alceste in Molière’s Le Misanthrope). It turns out that she runs an extortion racket, kidnapping mice to force their loved ones to steal food for her. But it also becomes evident that the culprit our heroes seek is not her, but somebody in their own ranks.

I remembered nothing of this plot, and even less of the supporting cast, when I sat down to reread the book. What I did remember from childhood readings was the mood and setting of the story. The deserted streets and interiors of the city at night, against which the story plays out; the empty shop floors and dusty attics; the dimly lit sidewalks and overgrown back lots. While the ‘story’ as such is fine and carries several surprises as well as interesting character moments, it is to me in the evocation of this environment, this city belonging to somebody else (the humans), that the true power and beauty of the comic resides. It is what had stayed with me since childhood and it is what resonated upon reacquainting myself with it.

I am not talking about just world-building here, although that can be an important element, but rather the kind of story told in ‘graphic strokes and by deployment of the whole panoply of cartoon effects and ways of seeing and representing’ that Campbell talks about. It is a story that only resonates further when one learns that Macherot drew it just after moving for work reasons from the countryside to Brussels, where he never felt at ease. Such behind the scenes knowledge is unnecessary, however, to experience its poetry of detail and sense of alienation. Other comics could give you much the same ‘story’, but only this one could give you that. It may not be Proust, but it is certainly a worthy work of art.

The critic R. Fiore calls such an understanding ‘the experience of comics.’ Campbell references Fiore’s capsule summation of the idea in a comments thread somewhere, but the Fiore himself clarifies it further in a recent comics review:

The Experience of Comics is a notion I half-baked some time ago to account for why comics strips can have a far greater aesthetic impact than their subject matter would imply. For example, at least five of those ten greatest newspaper comics strips cited above [in the review] hardly ever expressed an idea that wasn’t trite, absurd or patently false. The outlandish coincidences of Dick Tracy, the utter escapism of Wash Tubbs, the cracker barrel philosophy of Little Orphan Annie, these are elements that in prose would not have gotten past the lowliest hack pulp editor. What sustains this substance is the experience of inhabiting the subjective world the cartoonist creates. The writer of poetry or prose however vivid his imagery must depend on the reader’s internal image of the things he describes. The cartoonist doesn’t merely describe a tree, he determines what trees look like. And so with every person and object in the cartoonist’s world. While a painter also creates a subjective world, a painting or drawing is not a narrative. Where a painting or drawing begins and ends in one image, by implication one comic strip panel could follow another into infinity. If the cartoonist’s subjective world is vivid enough all the narrative really has to do is be engaging enough to draw the reader into it. This is why bad writing will defeat even the most accomplished comic art. Rather than drawing you into the comic strip, bad writing pushes you out.

As Fiore implies, all handcrafted images do this to a certain extent—albeit not always sequentially—so there is really little reason to give it a separate name. And the logic can be extended to photographic and digital images too, albeit with modifications. When you have images, there are non-literary forces at play and ignoring them or regarding them merely as a means to a literary end is reductive. And even though fandom has long fetishized drawing, it remains a critical blind spot.

* An example is Robert’s excellent essay on Eddie Campbell’s work, in which he integrates a perceptive analysis of Campbell’s narrative drawing. I may be wrong, but reading it seems to me as if the questions elicited by Campbell’s literary ambition prompted similar questions of the visuals. His discussion of Campbell’s debt to Henry Miller for example, for example, explains how Campbell’s drawings visualize the associative nature of Miller’s prose. Since we’re in critical mode here, I suppose I would argue that Robert takes less notice of how Campbell’s impressionistic tenor roots his meandering wit as a writer in cognitive realism, evoking like few cartoonists the visuality of memory. But that’s just building on an stimulating analysis.