I turn thirty this month, which means I’m officially an old fart. And like all old farts, I enjoy reminiscing about the past when everything, especially comics, were better. It’s time for some good, ole’ fashioned nostalgia. And since nostalgia tends to be infantile, why not look back at the comics being published during my first days as an infant? For the next two weeks, I’ll be reviewing the mainstream comics of September 1980, starting with the output of DC Comics.

Batman #327

Writer: Len Wein

Pencils: Irv Novick

Inks: Frank McLaughlin

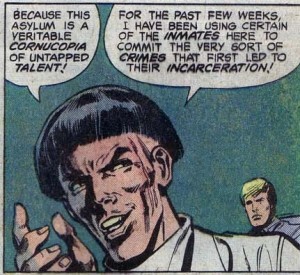

I don’t care for Irv Novick’s artwork. It’s genre hackery at its most tiresome: generally competent, but lacking any sense of location, character, or emotional intensity. Backgrounds are practically nonexistent, and not for any creative reasons that I can detect, but probably because Novick is lazy. To avoid drawing backgrounds, he brings the action close to the characters or fills the panels with talking heads. On the plus side, I’m amused that his depiction of Dr. Milo resembles an anorexic Moe Howard.

The shitty artwork is all the worse because it drags down a half-way decent story. Wein appreciates that Batman straddles the line between superheroes and pulp crime, and he liberally steals ideas from the latter genre. Rather than a straightforward hero vs. villain slugfest, the narrative is mostly a detective story with disguises, drugging, and identity confusion.

Unfortunately, the main story is only 18 pages long (to make room for a tedious Batman and Robin back-up), so Wein has to rush through the plot, spending just a few panels on each of the pulp crime tropes. The result is a story that practically begs to be a two-parter. On the other hand, that would require reading another issue drawn by Novick.

Action Comics #511

Writer: Cary Bates

Pencils: Curt Swan

Inks: Frank Chiaramonte

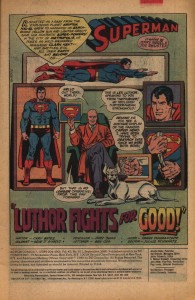

I’ll lay out my prejudices at the start: Superman is boring. He’s a boring character who stars in boring stories. Action Comics is probably not the worst comic being published in any given month, but I can’t remember when it was ever any good. And judging this comic solely as a superhero adventure, it largely confirms my bias. Lex Luthor goes good (I’m guessing it doesn’t last) and helps Superman in an unremarkable fight against two unremarkable villains. There’s also a section devoted to Clark Kent’s job as a TV anchorman, which is sadly no where near as entertaining as it could be. At the very least Curt Swan’s art is attractive, but he can’t elevate tedious plot or characters.

But for all it’s faults, I was actually entertained while reading this comic, thanks to to the fact that it’s incredibly gay (more so than Superman usually is). The opening splash page features Lex Luthor relaxing in a room decorated entirely with pictures of Superman doing heroic things, like flying, punching, um … standing, and … I’m not quite sure what he’s doing on the right. Rolling up a newspaper? Maybe it’s supposed to be an iron rod (insert your own joke here).

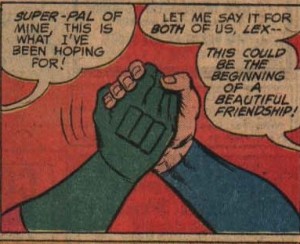

Plus, it ends with manly hand-holding…

Bros 4 Life

And in-between, Superman and Lex fight a gay, space cowboy. I suppose unintentionally entertaining is better than nothing.

Wonder Woman #271

Writer: Gerry Conway

Pencils: Jose Delbo

Inks: Dave Hunt

Poor Steve Trevor. DC would kill him off, only to bring him back, and then kill him off again in a desperate bid to wring some drama from Wonder Woman. Apparently, issue 271 was a big deal, because Steve Trevor is brought back to life (again). Except it wasn’t the “real” Steve Trevor, but another Steve from a parallel Earth who crashed through a dimensional barrier.

I don’t give give a shit about the DC multiverse, but I approve of this plot point. If there’s any real benefit to having parallel Earths, it’s that they provide a quick and easy way to throw out the previous writer’s terrible ideas. And then the current writer is free to introduce his own terrible ideas, which comprise the rest of this issue.

Justice League of America #182

Writer: Dave Cockrum

Pencils: Dick Dillin

Inks: Frank McLaughlin

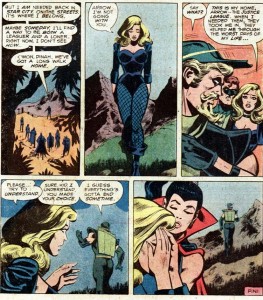

I really liked this, even though Dick Dillin’s artwork is uneven, and even though the the main plot was a rote conflict with Felix Faust that I already forgot. What stands out is the B-plot, starring DC’s premier asshole, Green Arrow. In the real world, nobody likes an asshole, but assholes are an essential ingredient for any great superhero team. Assholes get the best lines, assholes create drama, and, unlike the other good guys, the assholes possess something resembling a personality. And it’s always fun to see an asshole get his comeuppance.

The best part of this comic comes at the end. In an earlier issue, Green Arrow threw a temper tantrum and quit the Justice League. He spent most of this issue whining because he got stuck helping the other heroes save the world. After they defeat Faust, Superman offers Arrow a place on the League again, but, being an asshole, Arrow throws the offer back in his face. Then he reacts with outrage when he learns that Black Canary, his girlfriend/enabler, wants to have a life of her own in the League.

What an insufferable prick. I am entertained!

Jonah Hex #40

Writer: Michael Fleisher

Pencils and Inks: Dan Spiegle

Colors: Bob Le Rose

Even though superheroes dominated its line-up, DC never entirely abandoned the other genres. Jonah Hex was DC’s (ultimately unsuccessful) attempt to keep a Western in continuous publication. Why and how the Western genre declined across all media is a topic for another blog post. For the purposes of this post, I’ll note that Jonah Hex is a pretty good Western. Fleisher and Speigle don’t do anything groundbreaking, and they don’t have to. The tropes of the Western are simple, and they either appeal to the reader or they don’t: Indians, revolvers, saloons, and rugged individualists imposing order on a lawless environment. All Fleisher needed to do was take the tropes and construct a morality play where Hex acted tough and the villain was punished in a suitably ironic manner. Fleisher did just that, but he also added a comedic touch by treating Hex as a reckless idiot who managed survive mostly due to dumb luck.

I’m not familiar with Dan Spiegle, but his work on Jonah Hex is impressive, particularly the rich backgrounds and expressive faces. But much of the credit should also go the colorist, Bob Le Rose. Rather than the vibrant palette of the superhero genre, Le Rose used muted colors and earth tones that evoked an earthier, more “real” appearance for the Old West. And the colors add a darkness to the story, even during the daylight scenes, that echoes the darker, more brutal themes of the genre.

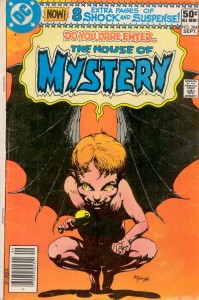

House of Mystery #284

Writers: J.M. DeMatteis (story 1), Carl Wessler (story 4)

Pencils and inks: Noly Zamora (story 1), Jess Jodloman (story 4)

That is a great cover.

House of Mystery was DC’s long-running horror/thriller/dark fantasy anthology. I’ve already talked at length about horror comics here, so I won’t belabor my earlier points. Suffice to say, comics are not an ideal medium for scary stories. Perhaps the best a cartoonist can hope for is to create a story that’s unnerving.

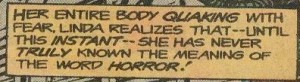

The lead story, “Ruby,” had some potential. DeMatteis crafted a decent plot about an evil little girl (20 years before the Japanese cornered the market on stories about evil little girls). Noly Zamora provided dark, atmospheric artwork. But at only seven pages, the story has no room to develop. Racing from one plot point to the next, what should be creepy descends into camp. And DeMatteis’ corny narration doesn’t help matters:

It’s worth mentioning that Alan Moore’s narration in Swamp Thing was equally overripe, and yet he somehow avoided diminishing his own story. But perhaps that’s an unfair comparison.

The rest of the issue consisted of similarly disappointing short stories. The last one, “Deadly Peril at 20,000,” is memorably solely due to its unabashed sexism (women are prone to violent hysteria, and the best way to deal with hysterical women is to kill them).

________________________________

Overall, September 1980 seemed like a lean month for a struggling DC. Marquee titles like Action Comics were stuck in perpetual auto-pilot, and the company’s non-superhero efforts were a mixed bag. But in November DC would launch New Teen Titans, which grew into an X-Men-sized hit.

And speaking of X-Men, next week I’ll take a look at what Marvel was doing 30 years ago.