We got a couple of really thoughtful comments on the Years Have Pants roundtable, so I thought I’d highlight them.

Tag Archives: Robert Stanley Martin

Robert Stanley Martin on The Playwright

In sync with our Years Have Pants roundtable, Robert Stanley Martin has published a review of Daren White and Eddie Campbell’s The Playwright

Fish without Bicycles: Feuchtenberger and the Distortion of Scopophilia

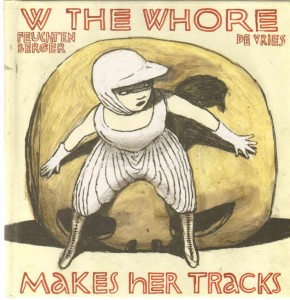

Over in the comments to Erica’s introductory post, Robert Stanley Martin commented that the art of Amanda Vahamaki’s The Bun Field (the subject of the last Fish without Bicycles) doesn’t appeal to him. I’ve heard similar things recently from male friends about both Vahamaki and Anke Feuchtenberger, specifically W the Whore Makes Her Tracks. Although Feuchtenberger’s drawings are sharper than Vahamaki’s with much more contrast, they’re aesthetically related (maybe someone with more art knowledge can give me some vocabulary here), and there’s indeed something about this aesthetic that doesn’t appeal to a number of men I know. Not all the men of my acquaintance – the book was recommended to me by a man. But women seem to like it more. It’s not a scientific sample, but it’s good enough to trigger a blog post.

In the same comment, Robert also called out an objection to French Feminism, specifically Hélène Cixous, who is perhaps best known for coining the term écriture féminine – used by all the French Feminists to describe a kind of richly metaphorical, non-linear writing that “inscribes the female body,” playing off the Pythagorean table of opposites and trying to embody the elements associated conventionally in the West with the female half of the table.

| Male | Female |

| Odd | Even |

| One | Many |

| Right | Left |

| Straight | Crooked |

| Activity | Passivity |

| Solid | Fluid |

| Light | Darkness |

| Square | Oblong |

In prose, this project often results in writing that is nearly impossible to parse; the (intentionally) less-than-comprehensible Marine Lover of Friedrich Nietzsche by Luce Irigaray (whom Robert also has issues with) is the definitive case in point.

Feuchtenberger’s work, in contrast, strikes me as far more successfully accomplishing Cixous’ ambitions for “women’s writing”:

“A world of searching, the elaboration of a knowledge on the basis of a systematic experimentation with the bodily functions, a passionate and precise interrogation of her erotogeneity.”

Her work “inscribes the body” with a crystalline clarity that the prose experiments never quite master.

Given that, and the apparent frequency with which men dislike this style of art, does the reaction against the aesthetic imply that it alone constitutes something like an “écriture féminine” for comics, something that is inherently, if unconsciously, challenging to male readers and empowering for women? It’s not impossible, especially if you’re very Freudian, but I don’t think so: The shadowy, filtered aesthetic gives a surreal quality that makes room for Cixous’ metaphorical, non-linear écriture féminine, but the aesthetic in itself isn’t sufficient to make that happen. Although it’s common to see this type of aesthetic deployed in the service of metaphorical or non-linear graphic narratives — narratives which are always, somewhat condescendingly, called “dreamlike” — the aesthetic doesn’t mandate any particular content, and I’m hesitant to gender a visual style independent of what it represents.

I find Feuchtenberger’s book remarkably more “feminine” than Vahamaki’s, but the gendered perspective is not in the aesthetic so much as in the imagery. I would not describe The Bun Field in Cixous’ terms, whereas they seem precisely appropriate for W the Whore Makes Her Tracks, despite the surface similarities in aesthetics (and with no implication of intent). Whereas Vahamaki’s text deals with the experience and perception of older children of both genders (a topic often interesting to women but not exclusively so), the subject matter of W the Whore Makes Her Tracks is explicitly sexed: the perspective not (only) of a woman’s mind but of the female’s body.

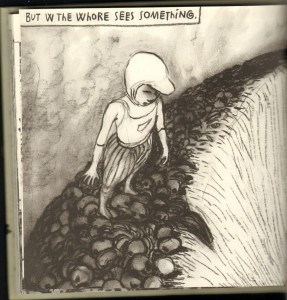

There is something very much interior about this style of art, something dark and fluid and in keeping with the right side of Pythagoras’s table. It certainly makes sense aesthetically for Feuchtenberger’s narrative. The perspective is intimate – no wide angle here – and the light is dim. The landscape is clearly imagined rather than seen; it does not yield readily to the creation of a “mental map”, except metaphorically. It is immensely difficult to orient yourself in space and impossible to orient yourself in time, except very slightly in terms of relative time internally to the narrative (such as it is.) The use of one panel per page rather than a grid enhances this sense that the story’s movement through time is less important than the visual metaphor of the landscape. The narrative is almost entirely metaphorical, and the overall effect is, again, either of the surrealist mindscape or the imagined Other-world.

But these elements are only obliquely “feminine,” and insufficient to account for any immediate aesthetic reaction against this kind of drawing. It seems wrong to say that men have an unconscious reaction against metaphorical, dreamy, non-linear stories. (One of the men who objected said, “It’s not that I don’t like it really. It’s that it looks like it’s going to be a lot of work.”)

Although the aesthetic itself is not gendered, it would surely be difficult for a man — at least a heteronormatively gendered man — to “recognize” the imagery in the book as true to his experience, especially the more metaphorical imagery:

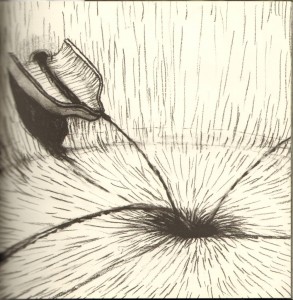

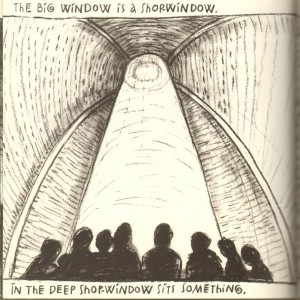

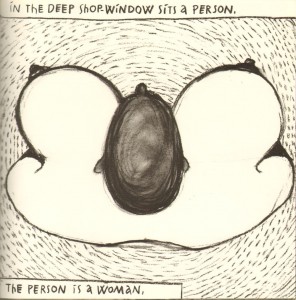

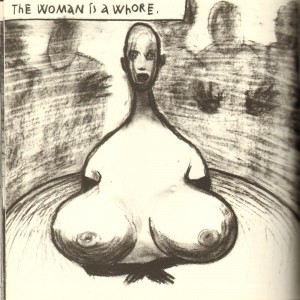

Feuchtenberger creates the contours of her landscape out of fragments of the female body during the sex act – but unlike most representations, the perspective imagines sex from the interior of the woman’s body:

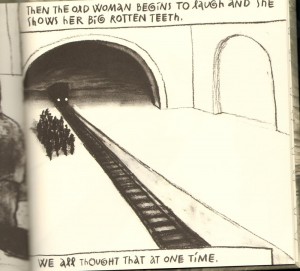

Of course, men can certainly “parse” the imagery – all the typical Freudian visual metaphors for sex make appearances in the book: tunnels and trains, phallic-shaped anythings, orchid-like flowers…they’re all there, and they still mean the same thing.

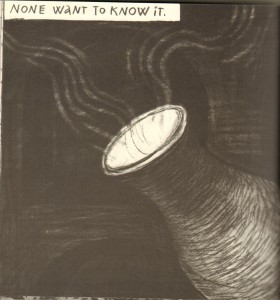

These images are semiotically packed: as stand-alone panels their signification is already varied. The last image for example is simultaneously (most representationally) the view of a woman from above, a view of sex from inside the woman, and a view of birth from outside. It also carries narrative significance for the book’s foregrounded conceit about sexual objectification and the marked-ness of the female gender.

But that turned-around perspective resonates more with a woman’s experience of her body…

…than with a woman’s visual image of her body, whether from the mirror, photographs, or a sexual gaze.

So what can we conclude from this? Despite this sexual subject matter, the book is not erotic. Bart Beaty comments, in a discussion of Feuchtenberg’s earlier “W the Whore” in TCJ 233, that “even in her nakedness none of the images are particularly sexualized.” Although I don’t have the earlier book to compare, the statement is true for this book as well, even though W the Whore (the character) is not naked very much in this volume.

But why is it that these evocative sexual images don’t have an erotic effect?Of course, they’re not intended to have an erotic effect, because that would undermine the critique of objectification. But what is it about them that interferes? Beaty’s observation puts into perspective not only how much our ideas about what counts as “erotic” are shaped by artistic (aesthetic/dramatic) representations of sex, but how conditioned we are to perceive even our own sexuality from the external perspective of most of those representations: “sexualized imagery” generally is based on something you can see during sex, not on things that you feel. Watching sex on TV or seeing sexually provocative images in a comic or illustrated book doesn’t replicate the experience of sex, it replicates the experience of voyeurism. This is – or at least has the potential to be – an immensely objectifying construct for both men and women, making sex less of an experience and more of a performance. To no small extent, the immense anxiety over body image that many women suffer is connected to this distorted, externalized perspective — as Feuchtenberger’s narrative explicitly points out.

Beaty describes Feuchtenberg as “exploring the outer margins of the comics form with seemingly no interest in making concessions” and “casting the very project of comics storytelling into doubt,” but I think this is too narrow a vantage point to accurately discern what makes this work so distinct an artistic achievement. The conventions of comics storytelling are no more called into question than the conventions of films and books for how to represent stories of women’s erotic experience. Comics form is part of the same broader culture of representation, and it is illuminating to shift the emphasis away from limited questions of form to questions about the extent to which gendered – in this case, sexed – erotic experience informs and shapes perception in general.

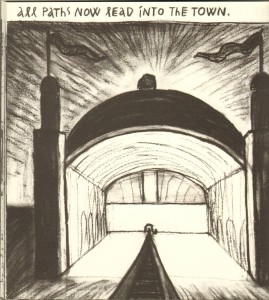

It’s a bit of a truism that women find erotic fiction much more arousing than erotic images, and Feuchtenberger’s perspective throws some light on why this is: representing the “inside out” experience of feminine sexuality is, on the surface, much more difficult in art than it is in words. Prose is appealing – and representational art vastly limited – for capturing interior experience: mind, imagination, sensation. In prose, you can just describe the experience, whereas the visual artist has to find a way to bring non-visual sensation to mind through visual means. Resonating with Cixous’ challenge to women writers, Feuchtenberger’s images make clear that French Feminism is profoundly physical but not in the least bit scopophilic. (The French Feminist emphasis on physicality has resulted in charges of essentialism by a great many Anglo-American feminists, including Susan Gubar, whom Robert also didn’t much like). When Feuchtenberger does represent scopophilia it is very distorting:

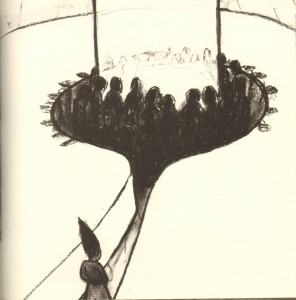

or creepy, represented by a crowd of anonymous watchers (also visible in images 5 and 6 below). The watchers represent that “experience of voyeurism” discussed above, and stand symbolically in the narrative’s interior space for the ways women internalize the perspective of these collective, objectifying voyeurs.

To parse the literal strain of the narrative, recognizing the distorting effects of this scopophilia is “freeing” for W the Whore, but ultimately futile.

Despite this rather despairing narrative thread emphasizing the futility of écriture féminine, Feuchtenberger’s text in conversation with Cixous’ is “freeing”: it allows us to see the effects of a cluster of binaries between text and image, voyeur and participant, inside and outside, seeing and feeling, male and female. W the Whore Makes Her Tracks illuminates the cultural insistence that “the body” is what we see from the outside rather than what we imagine and experience from the inside, and it turns that insistence “inside out.”

The conventions of illustration and representational art insist that we think of Feuchtenberger’s vantage point as “metaphorical” and “dreamlike.” And yet, Feuchtenberger’s most significant achievement in the book is very direct: the reminder that there is no reason why what we find erotic should be based on the perspective of the voyeur, and that there is so much more to the body than what that voyeur can see. Although I think it definitely matters that this book was written by a woman, it seems like that insight applies equally well for men.