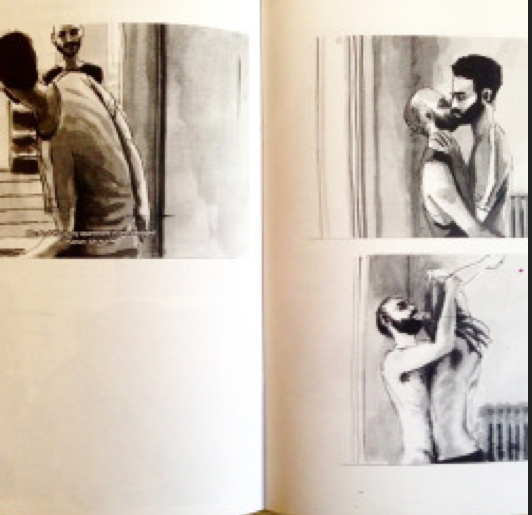

Sholem Krishtalka, Snax (detail), 2014

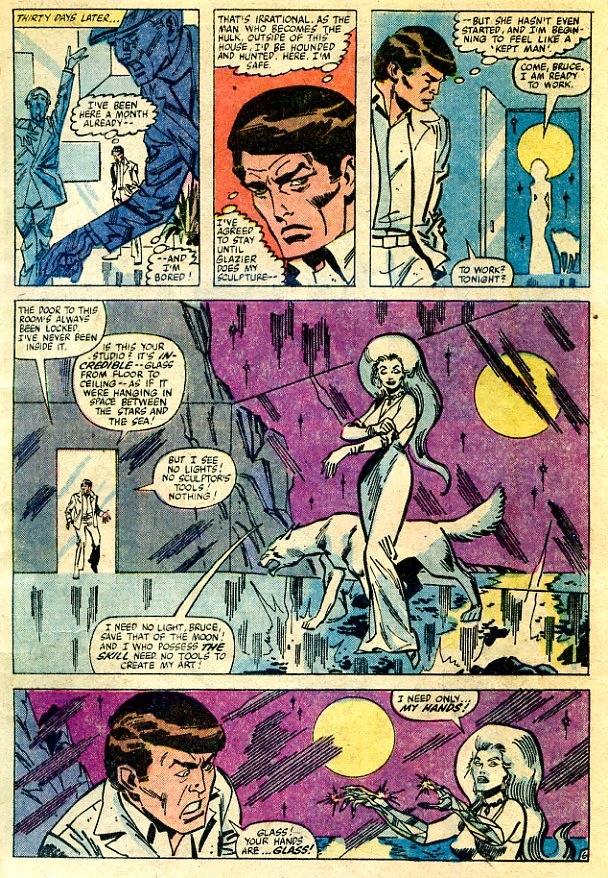

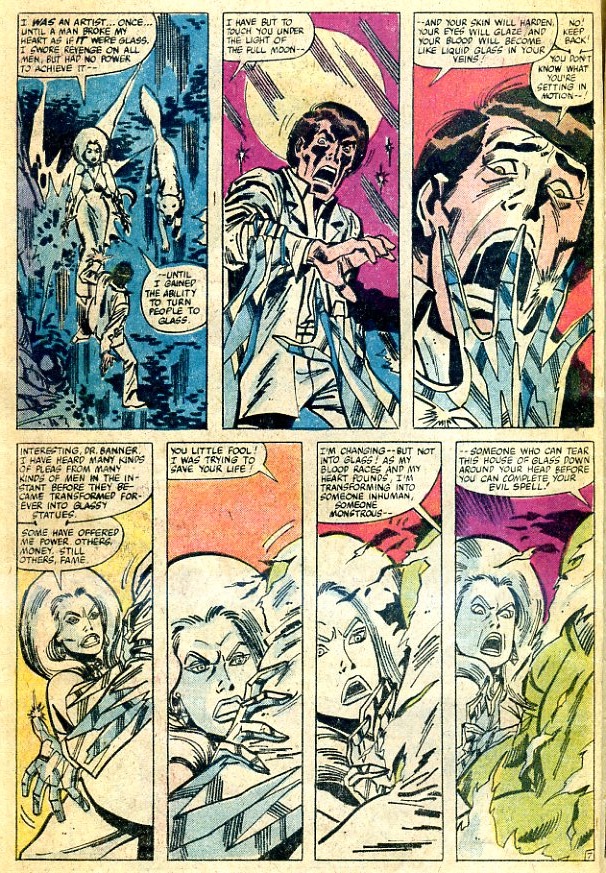

Sholem Krishtalka moved to Berlin a couple of years ago, and has been making visual and cultural representations of the city since May 2013. They are mostly online, scanned from analog sources. Looking at the work, with the pictures interlaced with text, they could be thought to be comics. Even talking to Krishtalka, he sees them as similar to Hogarth, the British painter and print artist from the 18th century. The two big books in the mid 1990s that tried to claim comic as art, or tried to talk about the semiotics of comics as their own thing, place Hogarth in their canon. For Scott McCloud, Hogarth is comics, because he fits their essential definition; namely, that they are “juxtaposed pictorial and other images in deliberate sequence, intended to convey information and/or to produce an aesthetic response in the viewer” (McCloud, Understanding Comics, 20). For Robert Girard, it is a possibility that Hogarth’s early work could be comics, and his entire first chapter is about the English tradition of printing, that reached its zenith in the 19th century.In this capacity, Hogarth and comics can be defined by “Skill for exaggeration and ironic juxtaposition of words and pictures…an aesthetic template” (12, Comics, Comix, and Graphic Novel)

From A Berlin Diary

Krishtalka work could be considered comics by Girard and McCloud–especially for the problems of (possibly ironic) juxtaposition of words and images. However, when he spoke to me he disputed this taxonomic claim: “It’s not created as a comic (this isn’t any form of snobbery, it’s just not constructed, laid out, etc etc the way a comic book is). If I have my way, it’ll look more like a monograph than a comic. Again, I’m interested in medium specificity — if it’s going to be a book, I want it to make sense as a book, i.e. I want the form of the book to impact the drawings and vice versa” Thinking about the art historical tradition in which Krishtalka works (the book and the print), the juxtaposition between words and text might not be the sole purview of comics or comix.

The art historical tradition could consist of the Los Angeles legend Ed Ruscha, who never claimed that his photographic work were works in themselves, but “pictures for a book”. By extension, Ruscha makes the point that his drawings are, in a similar fashion, just pictures in a book. But, this does not mean that pictures in a book cannot be juxtaposed.

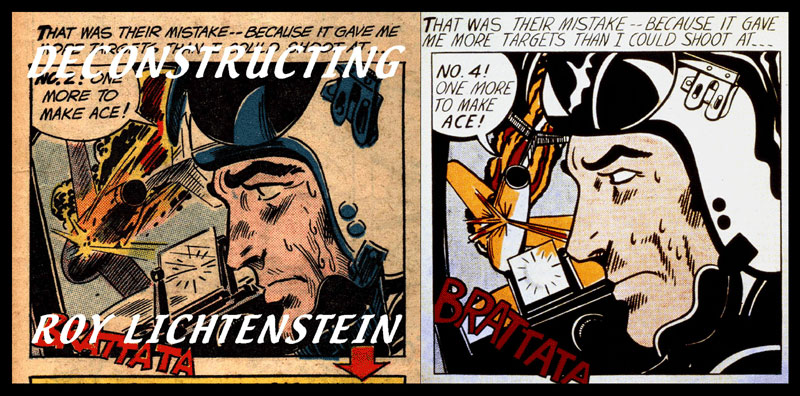

Ruscha’s use of banal texts — or his absence of text — asserts that the mash up of words and pictures is not the most interesting juxtaposition, which can occur within a set of formal choices, within or at oblique angles to a larger tradition of image making. The tradition becomes a kind of moving target that never quite remains stable. In this sense, the media becomes the message. Ruscha’s use of banal forms, or pop’s use of banal forms, are as much of a figure of media choices than other formal problems. Thus, the comics are comics, because Hogarth turned paintings into cheap etchings, which were then made even cheaper by vernacular forms. The translation into vernacular forms are more important than either words or pictures. To read a tradition is not to just read words or pictures, but to place both into a social context, which pays attention to the methods of production.

Ed Ruscha, from The Seasons

So, the “the juxtaposition of pictures and words”, in Krishtalka’s context, must be considered in the media tradition of queer narrative artists, in Europe, at the beginning of the 21st century who have a tense relationship to digital methods of distribution. Within this media are very specific messages, even messages that connect to Hogarth, but elide either comix or comics. This tradition, a half century earlier, would include David Hockney, especially his illustrations of certain poems of Cavafy or his work on the Rake’s progress.

Cavafy was a cult poet–Greek, friendly with the novelist EM Forster, and known for hinting at desire without stating sexuality directly. Hockney’s illustrations of the poems of Cavafy, make explicit the homoeroticism implied in the text. Thus, in this act of translation, the work allows for an explicit overlap between text and image. The lack of contrasting effect in the work means there is no juxtaposition between word and image This appropriateness refuses one tradition of seeing pictures and words together (they do not startle).

Hockney illustration for Cavafy’s poems

There are other ways of images and words working together where Hockney playing with Cavafy would work perfectly. There have been private presses from the beginning, printing queer erotic work, and for the idea of queer erotic work being passed from hand to hand. Homerotic work has medium concerns, has a tradition that cannot be included in the problem of genre. That these works eventually become public, and that Hockney makes them more explicit than Cavafy’s hints, has a kind of intertextual narrative progression. Cavafy writes tight, heart breaking odes of masculine sex. In a couple of decades, using a media that is both attached to a tradition and a break of tradition, Hockney illustrates these odes. These illustrated odes are scanned because of Hockney, and through the problem of the net, finally develop a kind of fissure. This fissure, between image and text, allows for an unmooring of desire. This ambivalence of forms and history, also through the net, can be seen in the best of Krishtalka work. It has an embodied disembodiment, which is shared by Hockney. The juxtaposition is between reader, author, tradition, medium and heritage. The words and the pictures matter less than all of the other concerns.

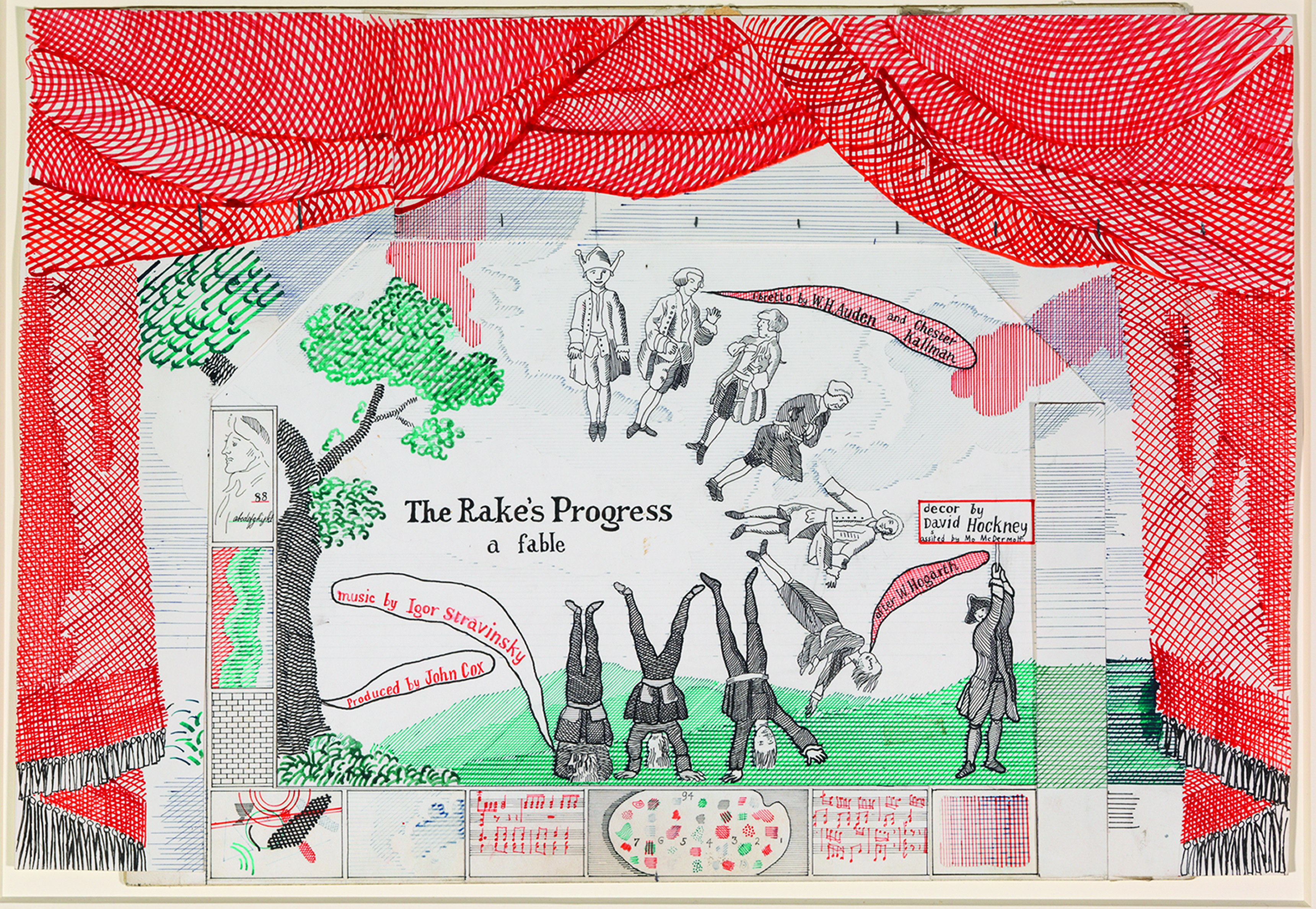

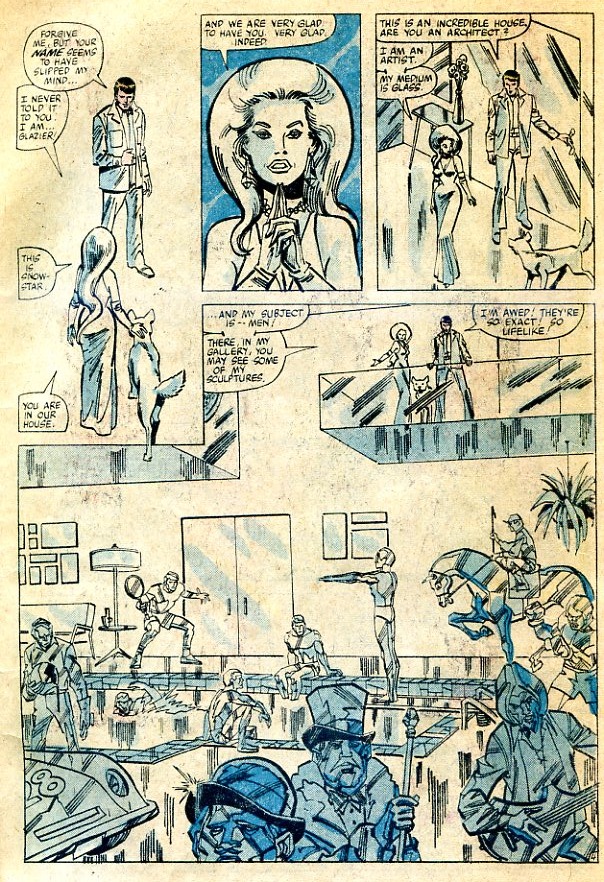

If Hockney’s etchings around Cavafy are about intimacy of scale, than his stage designs for Stravinsky’s operatic adaptation of the Rake’s Progress fit within a tradition of printmaking. That the libretto of the Opera was written by the poet WH Auden and his partner Chester Kallman indicates a queer reclaiming of Hogarth’s work. If the sexual outlaw was subject in Hogarth’s work and if the juxtaposition at least partially was between who was being depicted, and the audience for those being depicted, the making queer underground tradition epically visual. When Hockney uses the form of etching, he also turns those etchings into opera curtains–adding the performative nature of time to this ongoing hand to hand playing of the homoerotic potential of English masculinities. Thus, the work he did for the Rake’s progress does not juxtapose words and pictures but juxtaposes the oral and written languages in ways that are within the tradition (the tradition of English music hall, but also the tradition of opera queens and another kind of performative queerness.) The refusal of juxtaposition, the sameness that occurs with the updating of the etchings, suggest that not all pictures with words are comics.

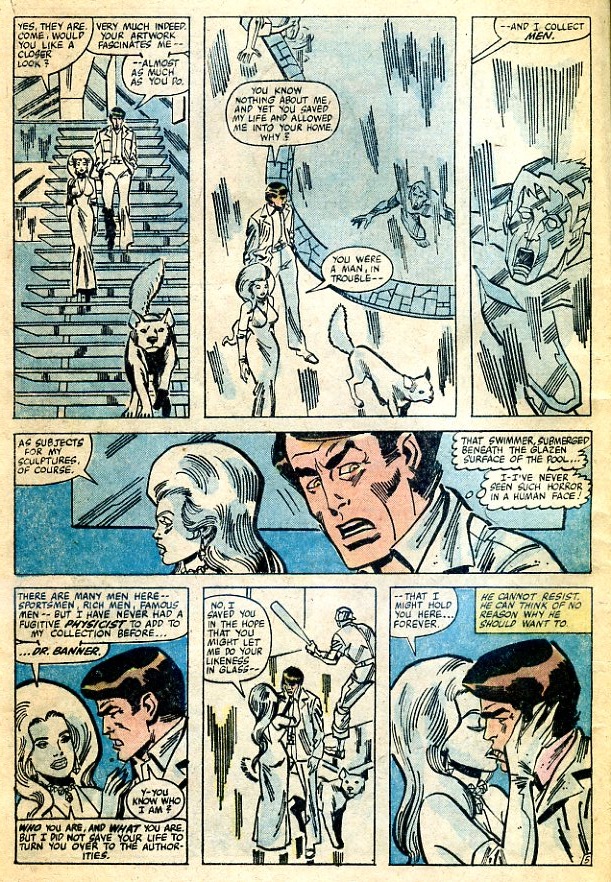

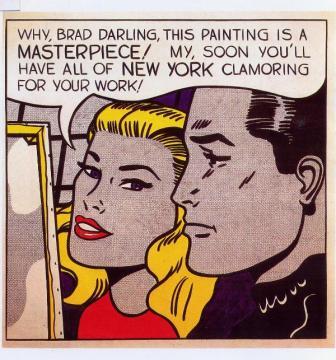

Hockney’s adaptation of Rake’s Progress functions as a formal act–where the medium becomes the message. It plays with the visual syntax of Hogarth but not the form. But then what to do with Cavafy’s etchings? As illustration, ephemeral, connecting perhaps to the cheap traditions of pornography and the expensive connections of private printed editions, but do they juxtapose? In Krishtalka’s depictions of the dance clubs of Berlin, is he functioning as an outside observer–juxtaposing audience and performer, or is he placing himself within a tradition of visual depictions–like Auden and Kallman writing an opera to make the visual queer? This is the ongoing problem of juxtaposition. It’s not a useful word for figuring out the complex lattice of forms that visual work constructs. The beginning assumption is that juxtaposition only exists within a context of high modernist shock. The integration of forms, and of medium, that rely on a familiarity of influences is not rewarded via juxtaposition. Outside of a comics context, the art historian Hal Foster writes about this on his introductory discussion of early pop. “Warhol and Lichtenstein’s ..juxtaposition of high and low registers might shock, but only in the first instance…it is the unexpected fit between tableau and its cultural others (cartoon, ad or comic) that counts…”(Foster, First Pop Age, 71)

David Hockney, The Rake’s Progress

How Hockney constructs his relationships to personal experiences, and selfhood is one unexpected fit. There are others. For example, Lichtenstein’s mirror paintings from the late 1960s to the mid 1980s, and how they both refuse a direct correlation between the narratives of self, and the medium of quoting, destabilizing forms. (They are pictures of mirrors that are literally unreflective). Even if Lichtenstein wasn’t queer– his work suggests that identity has become labile, more prone to failure, and less willing to endure the juxtaposed enjambment as the only way of moving forward. Krishtalka’s work approaches Pop’s move away from juxtaposition as a formalist identity, and towards a large series of unstable and negotiated allowances, not the usual beyond the fourth wall or the playing with panels, but with a recognition of multiplicities of media. Lichtenstein’s mirrors recognize the infidelity of the mirror’s ability to feed information back to the viewer. This tension between how something is represented, and what it shows, could be a continual central problem of contemporary aesthetics. Another example: Warhol was shit at silk screening, if he did it himself, it was splotchy, runny, the colors bleed. The formal instability of the silk screen medium, so close to the problems of painting, is a reminder of the continually instability of form, just as Lichtenstein’s mirrors which cannot see, resemble the idea of mirror, without embodiment. This is not to suggest that comics are incapable of this kind of reminder, but the juxtapositions that historians of comics keep trying to embody are not the only games that are being played. It might be useful to think of this as a number of spectrums: between future and past, between precedents, about identity (like queerness itself is a spectrum), between fidelity and infidelity to any of these problems–but also between soft introductions and hard shocks, between the primary shock and the continual renewal of problematic forms.

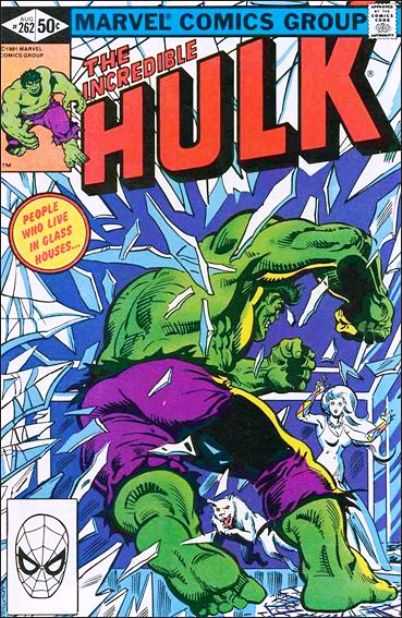

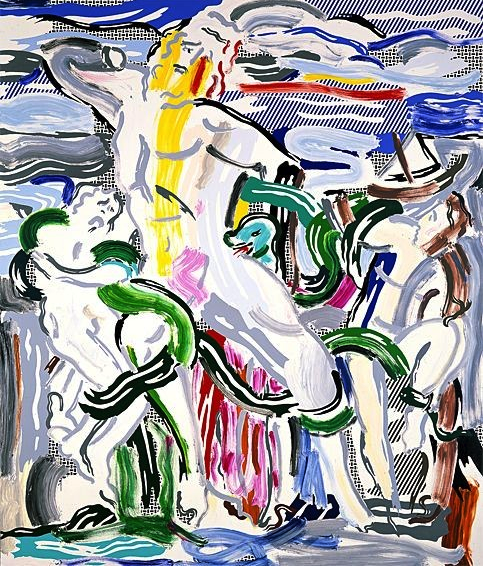

Roy Lichtenstein

Hogarth was straight and bourgeois, and Lichtenstein was as well, but the others we have mentioned had a queer heritage, and part of that problem of reproducibility has a queer energy. Part of the queerness is the ability of the private book, the broadsheet, the mimeograph, the computer, the smartphone, to allow for early adopters to invent and depict new sexual forms. Part of it is that queerness functions as a kind of paratextual interloper, it slides between genre or forms with some ease. Part of it is the artificial reproduction has a queer edge–eluding biology, eluding the ordinariness of how we usually create more things, the mechanical and later digital, allow for a wilderness of desire, that overwhelm simple understandings of one thing juxtaposing with another. This queerness then infects how narratives are constructed, but does not position a simple way of working through one form or one methodology.

These spectrums working with Krishtalka’s queer work and his historical canon, work out an ongoing problem of how to depict the visual impact of new reproductive media. One of the reasons why paintings become prints in Hogarth is because of the emergence of cheap and ready ways to do so. One of the reasons why Warhol worked in both film and in silk screens, was a way of finding his own identity in the history of mass production. The blankness of Ruscha is only possible because of the new interstate Highway system. The anxiety of Lichtenstein’s mirrors is about how to see in a new machine age. The ongoing problem of how to construct meaning in new narratives of image reproduction has a weird consistency.

This fraught relationship between how to see and what to see is not only visual. Krishtalka’s project is named the Berlin diaries. For most of Krishtalka’s audience, this brings to memory the novelist Christopher Isherwood’s Berlin Stories, which gave birth to a stage production, which gave birth to a film, which gave birth to another stage production. The interplay between film, stage, and written text was introduced by one of last century’s definitive opening lines, recalling an ironic visual neutrality of new technology: “ “I am a camera with its shutter open, quite passive, recording, not thinking. Recording the man shaving at the window opposite and the woman in the kimono washing her hair. Someday, all this will have to be developed, carefully printed, fixed.”

Isherwood wanting to be an impersonal camera, and never succeeding at it, summarizes a history of a whole tradition of 20th century attempts to answer the problems of the reproducibility of technology. Thinking about the series that Krishtalka did before he worked on the Berlin Diaries, this problem of reproducibility has some definitive queer shades. The series is called Lurking, and it is beautiful depictions of mostly watercolour and pencil of youngish, cutish men. They translate a form that has been popular from the Mannerist era, but the formal translation has something to say about the distribution methodology of the form (from Facebook to analog media, to digitial scanning, to Tumblr.) Though, this translation is one that Krishtalka disputes: “On the other hand, you’re always a victim to the speed of people’s dashboard feeds, and the culture of image consumption on the internet in general. Which means that people don’t linger on the images on the net, or at least I assume they don’t. What was interesting about watching people consume the images live, i.e. during the run of my gallery show, was that people really did linger.”

Looking at Krishtalka’s Lurking Drawings on Tumblr, reinforces the desire to linger, just as the desire to cruise, the desire to form one’s singular narrative, is complicated when they are imbued by other creators and other forms. The Tumblr feed is a collective feed, and one whose narratives are out of the control of the artist. They become a monstrous problem of this reproduced form. But the formal component is still vital. Lurking is part of that talk about the internet’s return of the visual, the tension of the digital, formal juxtaposition, all become part of this self perpetuating traditional crisis of narrative making. But a formal crisis and one interlaced with the usual problems of aesthetics (maybe even a problem of beauty.) So though comics flirt with the edges of this problem of reproducibility, is the problem of formal reproducibility explicitly one of comics?

In the hi/lo tumblr everything is visual without being explicitly within the form of comics or watercolour or prints–the problems of transmuting that the Cavafy etchings in texts are part of this construction, and the form of Lurking is more suited to Tumblr. The work will shift meanings and culture, when they are taken out of the visual stream of the tumblr wall, and emerge into a written book. Just, as our understanding of Hogarth changes, when we see what Hockney has done with it.

In this sense, comics becomes one way of looking at the juxtaposition of word and text, one way to translate, but not the simplest or the only method. The book refuses the juxtaposition, and abstraction of the digital form, as Krishtalka allows: “My ultimate ambition for this project is that it be concrete, that it exist as a book. If this ever does see the light of day, it won’t look like a comic. It’s not created as a comic (this isn’t any form of snobbery, it’s just not constructed, laid out, etc etc the way a comic book is). If I have my way, it’ll look more like a monograph than a comic. Again, I’m interested in medium specificity — if it’s going to be a book, I want it to make sense as a book, i.e. I want the form of the book to impact the drawings and vice versa.”

The Berlin Diaries as they are working right now (as text, as writing, as a cohesive way of working through identity, as a piece aware of and working around these traditions, as a problem of desire, as a problem of medium, as an edited work, as a work of excess, as a print series, as a work of nostalgia, as a work that is unstable in a medium that is unstable, as queer–not in the subject matter, but as a formal problem) refuse juxtaposition in favour of more explicit forms (what Krishtalka calls “medium specificity” When they become a book, the concreteness of the form does not make them any more of a comic, just as when Hogarth moved from paintings to prints, they were the proto comics that we wish them to be.

The transformation is the key taxonomic category, but not the singular one.