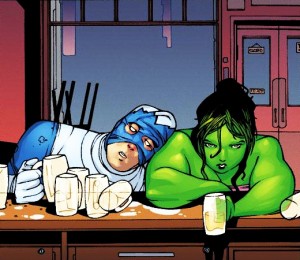

A lot has been written about Matt Fraction et alia’s run on Hawkeye. For example, see here for a HU discussion of the early issues, and here for a discussion of its depiction of disability in comics. I want to focus on issue #19, which is often discussed for its depiction of disability. The depiction of disability (or lack thereof) is an extremely important issue in comics studies, and I highly recommend Jose Alaniz’s excellent Death, Disability, and the Superhero (2014) for the reader interested in this topic. But I want to use issue #19 to examine a different issue – one that won’t surprise those of you who have read my other posts on this site. What I want to suggest is that Hawkeye #19 challenges our conception of what a comic book is.

A lot has been written about Matt Fraction et alia’s run on Hawkeye. For example, see here for a HU discussion of the early issues, and here for a discussion of its depiction of disability in comics. I want to focus on issue #19, which is often discussed for its depiction of disability. The depiction of disability (or lack thereof) is an extremely important issue in comics studies, and I highly recommend Jose Alaniz’s excellent Death, Disability, and the Superhero (2014) for the reader interested in this topic. But I want to use issue #19 to examine a different issue – one that won’t surprise those of you who have read my other posts on this site. What I want to suggest is that Hawkeye #19 challenges our conception of what a comic book is.

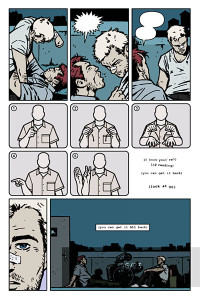

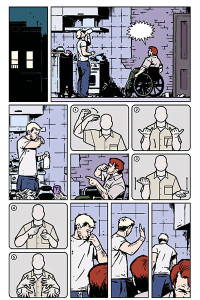

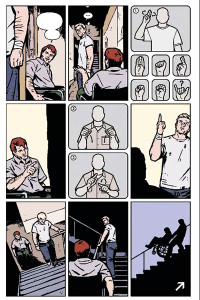

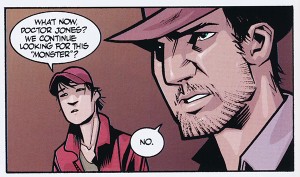

Hawkeye #19 is notable in that much of the communication in the comic occurs via pictorial representation of American Sign Language (ASL) rather than traditional speech balloons. Clint Barton is (once again) deaf due to an injury that occurred in the previous issue, and this is powerfully linked to his hearing impairment as a child – hearing impairment due to his father’s physical abuse. As a result, most of the communication in the comic (even in flashback scenes) is carried on via ASL, and language spoken by characters other than Clint is often depicted as empty speech balloons, with the shape or texture of the balloon itself roughly indicating emotion or emphasis, thus depicting this verbal communication (or lack thereof) from Clint’s perspective.

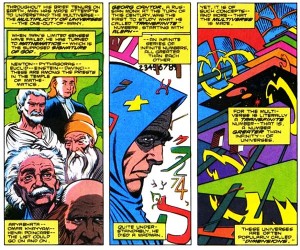

Now, in the academic and critical literature on comics, we are often told that one of the distinguishing features of comics is its unique combination of text and image. Of course, we know that there exist comics without any text – so called silent or mute comics. Marvel even had a special one-month ‘Nuff Said event in 2002 where many of their top titles published issues that contained no text. Nevertheless, textual information (in the form of dialogue, narration, SFX) is clearly a standard feature of comics. Furthermore, the special way that images and text interact, when both are present, is clearly an important feature of comics, since these two communicative modes interact differently in comics than they do elsewhere. Thus, explaining the way text and images interact within comics is (rightly, I think) taken to be one of the important outstanding problems in the academic study of comics.

Now, in the academic and critical literature on comics, we are often told that one of the distinguishing features of comics is its unique combination of text and image. Of course, we know that there exist comics without any text – so called silent or mute comics. Marvel even had a special one-month ‘Nuff Said event in 2002 where many of their top titles published issues that contained no text. Nevertheless, textual information (in the form of dialogue, narration, SFX) is clearly a standard feature of comics. Furthermore, the special way that images and text interact, when both are present, is clearly an important feature of comics, since these two communicative modes interact differently in comics than they do elsewhere. Thus, explaining the way text and images interact within comics is (rightly, I think) taken to be one of the important outstanding problems in the academic study of comics.

Nevertheless, even if all of this is right, and understanding the image/text combination in comics is important for understanding traditional comics that limit themselves to images and text, Hawkeye #19 demonstrates that this way of understanding the nature of comics is artificially limited. Now, Hawkeye #19 does contain a bit of textual dialogue, but let’s ignore that – Fraction et alia were clearly attempting to make an interesting and challenging experimental comic within the confines of mainstream superhero media, but were not interested, we can assume, in satisfying some absolute “no dialogue whatsoever”, Dogme-style constraint. But we can easily imagine a very similar comic that only communicated via (1) representational pictorial images and (2) inset depictions of communication via ASL. The question then becomes: what would such a comic teach us about how stories are constructed in comics? Before attempting to answer this question, two observations are worth making.

First, the depictions of communication via ASL within the comic (and within our similar, imagined entirely text-free comic) are not presented as straightforward depictions of the characters as they appear to each other when actually communicating in this manner within the narrative. Sometimes these scenes are depicted in this manner, but in many other cases the ASL is presented within inset panels that much more resemble pictorial instructions regarding how to sign than they resemble depictions of superheroes and other characters actually signing. In other words, these depictions of ASL are as much, or even more so, conventionalized and stylized depictions of the relevant communicative mode as are speech balloons within less experimental comics.

First, the depictions of communication via ASL within the comic (and within our similar, imagined entirely text-free comic) are not presented as straightforward depictions of the characters as they appear to each other when actually communicating in this manner within the narrative. Sometimes these scenes are depicted in this manner, but in many other cases the ASL is presented within inset panels that much more resemble pictorial instructions regarding how to sign than they resemble depictions of superheroes and other characters actually signing. In other words, these depictions of ASL are as much, or even more so, conventionalized and stylized depictions of the relevant communicative mode as are speech balloons within less experimental comics.

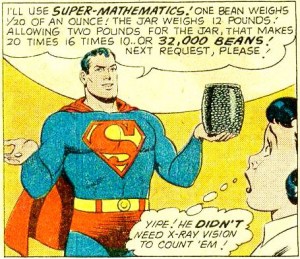

Second, these depictions of ASL are not text. Both text and ASL are conventional, primarily word-based modes of communication. But static images of a character signing are not, nor do they contain, the relevant ASL signs in the sense that an image of words contain those very words. The reason is simple: signing is dynamic and temporal, and text is static and atemporal. Further, text is compositional, while images are not. Hence static atemporal images of ASL signs are neither ASL signs themselves nor are they some sort of text encoding ASL signs.

Now, what does all of this suggest about traditional ideas regarding the centrality of image and text, and the interaction between the two, in comics? Well, the most obvious thing to point to is that the traditional text+image account of the nature of comics is far too narrow, since it won’t address the equally interesting and fruitful role that (pictorial depictions of) ASL can play in a comic, as evidenced by Hawkeye #19. More generally, what it suggests to me is that comics are not characterized by the interaction between image and text, but rather by the interaction of any number of static (unless we want to complicate things by bringing motion comics and the like into the discussion) visual modes of communication, whether these be representational images, text, conventionalized and stylized instruction-book like images of American ASL, or any of a host of other visual modes of communication.

Now, what does all of this suggest about traditional ideas regarding the centrality of image and text, and the interaction between the two, in comics? Well, the most obvious thing to point to is that the traditional text+image account of the nature of comics is far too narrow, since it won’t address the equally interesting and fruitful role that (pictorial depictions of) ASL can play in a comic, as evidenced by Hawkeye #19. More generally, what it suggests to me is that comics are not characterized by the interaction between image and text, but rather by the interaction of any number of static (unless we want to complicate things by bringing motion comics and the like into the discussion) visual modes of communication, whether these be representational images, text, conventionalized and stylized instruction-book like images of American ASL, or any of a host of other visual modes of communication.

Of course, this should have already been obvious, if one pays close enough attention to comics. After all, there is another static visual mode of communication, distinct from both text and image, that occurs frequently in comics: musical notation. Note that musical notation is usually used in comics, not as an actual notation to indicate a particular work of music, but instead as an indication of the presence of music without indicating which work or sometimes even which style (counter-instances in Schulz’s Peanuts notwithstanding). And of course Mort Walker long ago published his compendium of similarly-functioning emanata titled The Lexicon of Comicana (2000). So the idea that comics involve other modes of visual communication beyond representational images and text (in narration, dialogue, or SFX form) is far from new.

Nevertheless, Fraction et alia do give us something new in Hawkeye #19: an experimental comic that demonstrates the wide range of visual communication strategies open to comics creators by utilizing a novel such strategy: visual depictions of ASL. Thus, although the theoretical point is not new, this comic does represent a new way of making it, and a new way of making comics.

I’ll conclude in the time-honored PencilPanelPage fashion, with a question. If Hawkeye #19 shows that pictorial depiction of ASL can be used as one of the multitude of visual depictive modes in comics storytelling, then does that mean that visual depictions of ASL are always comics? Note first that a similar inference doesn’t go through for text (on any but the most generous accounts of what, exactly makes something a comic): text is a much more familiar mode of visual communication in comics, but not all strings of text are comics (even if it seems to be at least theoretically possible to construct a comic that does consist solely of text – see my own “Do Comics Require Pictures? Or Why Batman #663 is a Comic” in the Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism). But a work that consisted solely of visual depictions of characters communicating with one another via ASL would, at the very least, look much more like a comic than a typical prose-only novel or short story would. So, if we were to take a short novel – Paul Auster’s City of Glass, say – and translate it into ASL, and then make an individual drawing of an anoymous narrator signing each word in turn, and then print the results – say, six such images per page, in the proper order – is the result a comic?

In a

In a  Note that Jessica Abel and Matt Madden codified a version of both of these ideas (but from a production orientated, rather than a consumption orientated, perspective) in the title to their first how-to book on comics!

Note that Jessica Abel and Matt Madden codified a version of both of these ideas (but from a production orientated, rather than a consumption orientated, perspective) in the title to their first how-to book on comics!

Second, the above simple version implies that any comic involves a coherent narrative of some sort. Andre Molotiu, editor of the amazing

Second, the above simple version implies that any comic involves a coherent narrative of some sort. Andre Molotiu, editor of the amazing