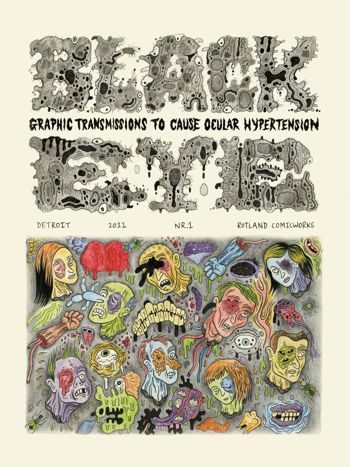

A while back, editor Ryan Standfest asked me to contribute to his black humor comics anthology Black Eye. I wrote a piece for him, but it turned out not to be what he was looking for, and he decided not to print it. The rejection did spark an interesting back and forth about black humor, faith, and other issues.

Black Eye has since been released, and Ryan kindly sent me a copy. The below is less a review than a way of continuing our conversation.

____________________

“It is our duty to give our readership whatever they wish to choke down, hoping it gets lodged in their throats….Sometimes you just have to go for broke,” Ryan Standfest writes in his preface to his anthology Black Eye. In doing so, he neatly encapsulates the dilemma facing the dangerous avant-garde. That difficulty being that the dangerous avant garde has been around, now, for more than a century. Artaud, arguably, was scary. Crumb, maybe was shocking. But if you’re preparing the same recipe Artaud did, are you really creating something your readers can’t digest? If you’re walking in Crumb’s footsteps, are you really going for broke? Or to put it another way, how can you shock the bourgeoisie when shocking the bourgeoisie is by now so thoroughly bourgeoise?

Black Eye has a lot of lovely work, and managed to freak out Canadian customs officials. But it never really manages to figure out how to get around the central dilemma of the unoutrageousness of third-hand outrageousness. The more it rages against the machine, the more overdetermined and reverent it seems.

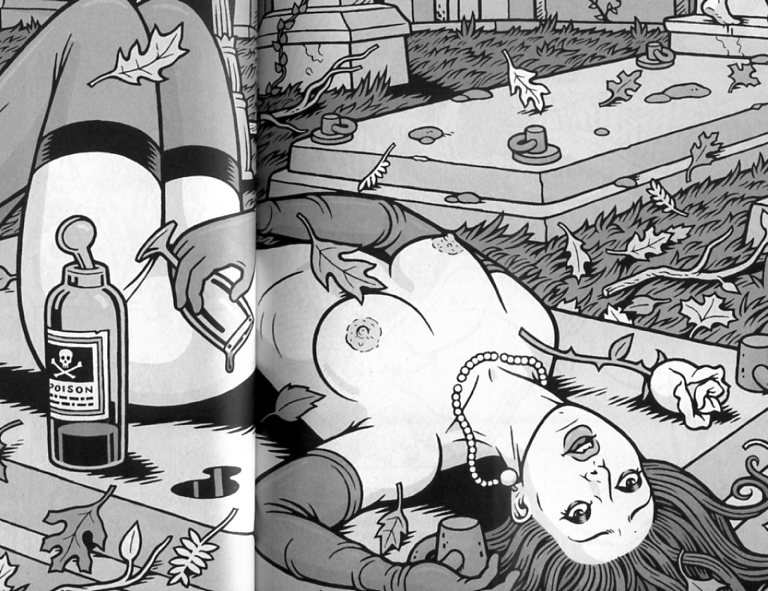

For example, Michael Kupperman’s advertisement for All-Purpose Animal Groinologues, which will allow you to correctly reference various vertebrates’ reproductive organs for important business presentations, is up to his usual standards of hysterically goofy humor — but it fits comfortably into a genre of comics advertising satire that long since passed through pointed and on into nostalgia. Similarly, Danny Hellman’s two-page spread showcases his usual strikingly clear and accomplished graphic style…but the image of a nude woman dead in a graveyard, tits visible and nether bits carefully covered, seems less like a brutal fist in the face of hypocritical contentment, and more like the sort of casual misogynyist imagery underground-influenced comics artists draw because that’s the sort of casual misogynist imagery comics artists draw. Similarly, Onsmith’s one-panel gags are little more than reiterations of frat-boy gross-outs without the inventiveness of Harold Ramis or the Farrelly Brothers, much less Crumb. Shooting dogs is funny, peeing on homeless people is funny, chopping up women is funny, necrophilia is funny all just in and of themselves because, damn it, being a black humorist means rotely following the tropes of your forbearers without ever having to add an iota of your own imagination. More successful is Gnot Gueddin’s surreal tale of butt-faced fisherman, demonstrating that you can water down Kafka a lot and still get something fairly entertaining. And then there’s Roland Topor’s “100 Good Reasons to Kill Myself Right Now” which is mainly amusing because it reminds you that, oh yeah, those goofy French! They are so cute with their berets and their wine and their nihilism! Oh, by the nose of Gerard Depardieu, that is dark!

Detail from Danny Hellman’s Black Eye centerfold

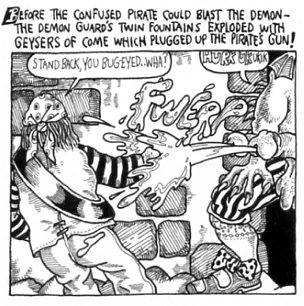

But Black Eye’s difficulties are perhaps most clearly summarized by its essays. All written by prominent comics scholars, the pieces are careful, well-written and, inevitably, devoid of the bite that they claim to champion. Ken Parille defends Ditko from the moral animadversions attendant upon his objectivist philosophy by summoning up Crumb and Lenny Bruce and declaring that like them “Ditko attacks the status quo, ridicules government and religion, exposes hypocrisy, and, most importantly, sees irony and humor wherever he looks.” Jeet Heer, in similar vein, insists that S. Clay Wilson is not a misogynist or a narrow moralist but that his comics, which occasionally depict homosexual sex, are, therefore, “A Visual Stonewall,” which, like the gay rights movement “speaks to…the new spirit of freedom.” Whether or not you agree with the aesthetic assessments, the intention is clearly hagiographic; you’re supposed to reverence Wilson and Ditko for their brave irreverence. All the idols have already been toppled, and there’s nothing for the nascent black humorist to do but idolize those who did the toppling.

Panel from S. Clay Wilson’s “Star Eyed Stella from Zap Comix No.4, 1969, reprinted from the original art in Black Eye in conjunction with Jeet Heer’s essay

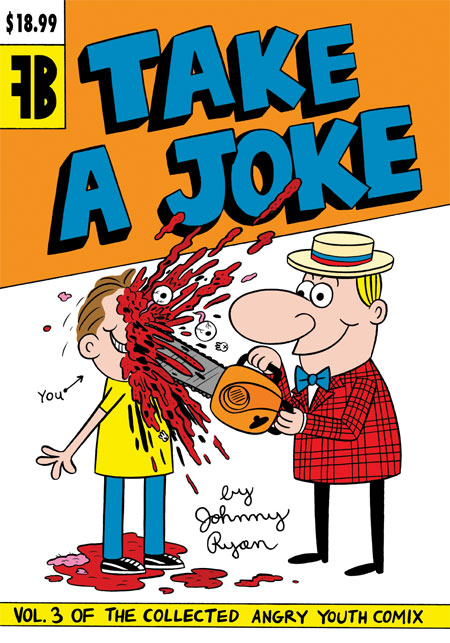

It’s instructive to turn to perhaps the most aesthetically successful contemporary comics black humorist, Johnny Ryan. Ryan’s Angry Youth Comix #12, reprinted in his latest anthology Take a Joke is devoted to “Boob Pooter’s Jokepocalypse.” Pooter, for those unfamiliar with Ryan’s work, is a world-famous comedian dressed in a cheap suit who specializes in hyperbolic offensiveness. In the Jokepocalypse, for example, he sprays people with Holocaust juice, turning them into lampshades; cuts off a soldier’s hand and sticks it in the soldier’s ass; launches a fleet of horribly destructive pity-fuck missiles; frees the breast cancer odd couple from the “cancer bags” of the President’s wife; goes back in time to kill Abraham Lincoln before he can sign the Emancipation Proclamation, resulting in slavery never being abolished; and kills a KKK member in order to cut him open and fly around in his corpse.

Pooter is, in other words, an anarchic black humorist, spitting in the eye of the proper and ejaculating blood upon the PC. Moreover, Pooter is not merely treated to hagiography, but is in fact deified. Pooter isn’t just some comedian; he’s a comedian with godlike powers. For one of his jokes in AYC #13, Pooter shoots himself in the head, comes back as a ghost, enters a woman’s body and masturbates until ghost sperm comes out of her mouth. In AYC #14 a (now-living) Boots elaborately ruins a man’s life, and when the man enacts revenge by killing him, Boots survives through a dizzyingly improbable series of disguises and substitutions, in which it starts to seem like Pooter is everyone and everyone is Pooter. He becomes a kind of immortal, unkillable demon, murdering and torturing in the name of cheap laffs and shallow boredom.

In some ways, Ryan’s use of Pooter is similar to Chris Ware’s use of God in some of his early Acme Novelty Library Work. For Ware, God (in tried and true black humor fashon) is revealed to be a megalomaniacal pissed-off superhero spreading brutality indiscriminately throughout the world. The difference, though, is that God for Ware acts out of sadism and cruelty — not out of a desire to make people laugh. Pooter’s a comedian, which means that he is, fairly directly, a stand-in for Ryan himself. Ware’s “God” satirically reveals the cruelty of the world; it’s a bleak joke on the ogre father. Ryan’s Boobs Pooter satirically reveals the cruelty of Ryan, who doesn’t so much want to upend the ogre-father as he wants to become him. Thus, while cruelty may be fun, it’s not exactly liberating. Pooter, isn’t a revolutionary; he’s a fusty stand-up man, beloved by even the President of the United States — sort of a mean-spirited Ed McMahon. Black humor, for Ryan, isn’t sticking it to the man in the interest of freedom. It’s sticking it to the man in the interest of taking his place — with the understanding that the man is all the more the ogre-father because he’s really just a bored dick.

If you gave Boobs Pooter Black Eye — with its lushly printed Onsmith/Paul Nudd cover, its witty Momma /Medea mash-up by R. Sikoryak, its lyrical surreal comic by Lilli Carré, and, yes, its thoughtful and enlightening essays by Heer and Parille and Bob Levin—if you gave Pooter this anthology, he would vomit Holocaust juice on it. That’s not Black Eye’s fault; Pooter’s a soulless cretin. As such, he defecates, not just on the staid squares, but on the anarchic rebels, until they’re both so slick with feces that you can’t tell the difference between them. Contemplating the mess, it’s hard to see black humor as a romance with daring heroes who courageously upend all values. Instead, it starts to smell a lot like just another stupid laff.