The entire Marston/Peter Wonder Woman roundtable index is here.

________________

In Part 1, I laid out some problems with Marston’s notions of the “good guys,” the women in power, i.e., Wonder Woman and the Amazons. In Part 2, I first look at a more fully realized female ruler in a mythical realm, then move on to consider some women of fantasy who resist the dominant power.

Wonder Woman and the Queen Regent

Since we’re talking fantasies, I prefer my castrating terrorism to be much more directly and, you could say, honestly horrific. Don’t pretend that the Amazonians aren’t another instance of a power fantasy with subjugation of the individual will being the goal — that it’s not just as frightening an idea as any other fascistic dream — simply because it’s gynocentric.

As a corrective to Marston’s gendered (I’d say sexist) approach, consider Queen Cersei Lannister from George R. R. Martin’s A Song of Ice and Fire and its TV adaptation, Game of Thrones. As she constantly reminds us, this is a patriarchal society, so she was born with a certain chromosomal disadvantage. Her twin brother Jaime assumes the propriety of the patriarchal rules, whereas femininity requires her to study them for loopholes. Like her mythological namesake, she turns men into pigs – albeit, not through witchcraft, but by her own sexual allure and ability to manipulate the rules of the dynastic game. Camille Paglia could’ve been thinking of Cersei when she wrote: “Man has traditionally ruled the social sphere; feminism tells him to move over and share his power. But woman rules the sexual and emotional sphere, and there she has no rival.” [p. 31, Paglia] As the best femme fatale in recent memory, she uses what the gods gave her to manipulate those (men and women) around her into achieving her will (she removed her husband, King Robert, for one). She’s as sexualized, duplicitous and dangerous as her predecessors in film noir, but with a different emphasis.

Martin takes a lot of care in establishing the difference between the way patriarchy imagines itself and the way it actually operates. One’s rule is established in the last instance by convincing enough people to believe in it. Those who really serve the ideology as it presents itself – the patriarchal image as a code of honor, honesty, self-sacrifice and all the “manly” virtues – tend to get their heads handed to them, like Ned Stark. But ideology requires for its continuance that we still act as if we believe in it. Cersei would have no power if the system collapsed, so she has to play a role that’s coded as feminine. To paraphrase her dwarfish younger brother, Tyrion, it’s better to be a rich cripple than a poor one. At an even greater genetic disadvantage than his sister, he, too, must be deceitful in order to make the system work for him. Thus, contrary to film noir, deceit isn’t really a feminine trait (any more than it’s a matter of dwarfishness), but a requirement of anyone who’s coded as other in a system that grants one power. Power is androgynous; any gender encoding is ultimately arbitrary even though it still has a practical effect on access. In Season 2 (Episode 1), when Littlefinger attempts to assert power over Cersei with knowledge that her son, King Joffrey, isn’t the “rightful” heir to the throne (being borne of an illicit affair between Cersei and her twin), the Queen Regent provides the lesson that, however she might’ve come by her influential position, “power is power.” As with knowledge, masculinity shouldn’t be confused with power itself.

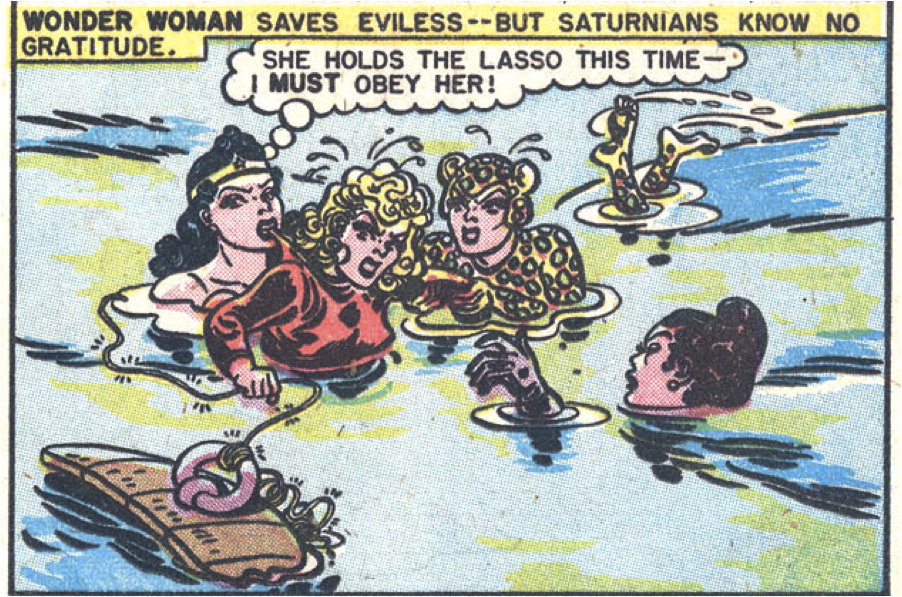

Wonder Woman and the Final Girl

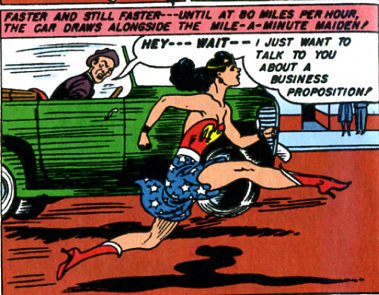

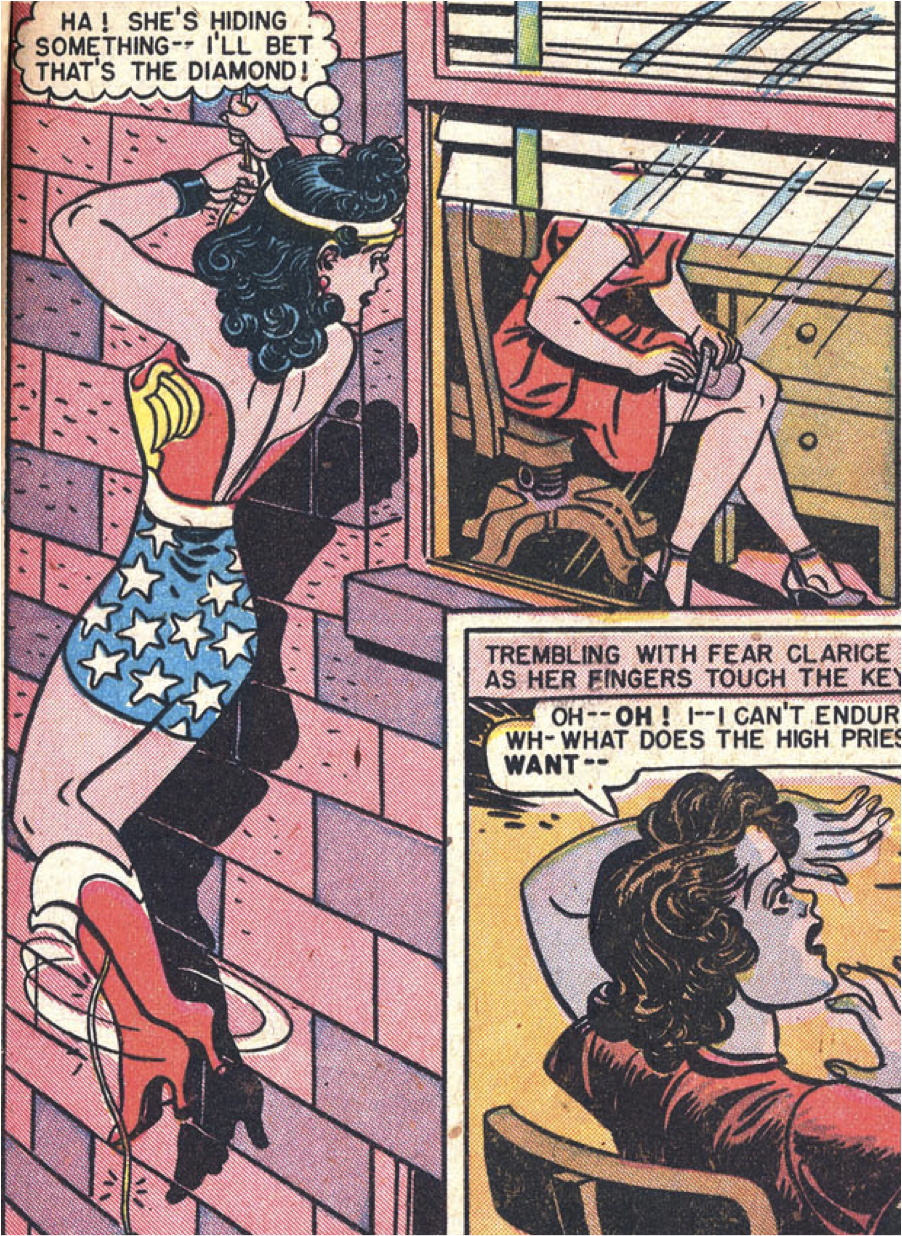

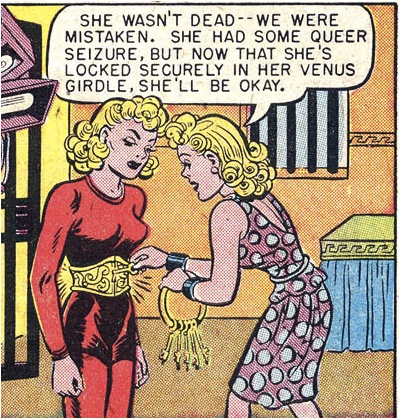

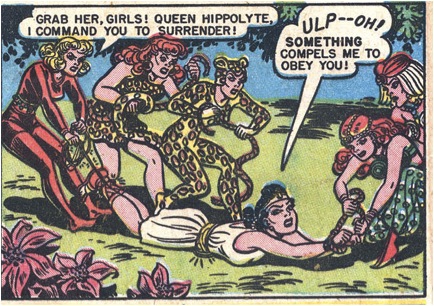

In keeping with the broadly stated alignment of masochism/submission/feminine and sadism/domination/masculine that’s the basis for gaze theory (the camera being a sadistic male voyeur that dominates the female spectacle), Wonder Woman is more the former than the latter. Although Wonder Woman regularly uses dominating tactics (the lasso, fisticuffs) they’re always reactive (the villain strikes first). Like Billy Jack, she wants to love, not fight, but she’ll kick your ass if you force her. There’s no question why the Saturnic girls hate Paradise Island so much; it’s clearly better than their home. [p. 4] We have nothing to fear from the Amazonian matriarchy, because it’s as submissive as we’re supposed to be. They only use psychic domination on caricatural villains. This is your basic superhero moral gobbledygook, only encoded as feminist. Azzarello got something right in his interpretation: if this were a rape/revenge movie, the Amazonians wouldn’t be the avenging party. My sympathies lie with Eviless. [p. 9]

Marston might be promoting a submissive morality, but there’s not much of a masochistic aesthetic to along with it. Wonder Woman is the dominating will. When she’s bound, it’s always wrong. The reader is to identify with her regaining control, making others submit. Similarly, Wonder Woman does a lot of hitting, but is rarely hit herself. (I count only once: Giganta nails her with a club. [p. 44]) Therefore, this is a relatively painless masochism. And that’s basically Marston’s ideological sleight-of-hand, selling submission as a pleasurable form of domination. A boy doesn’t have to fear the loss of control (“castration anxiety”), because he’s identifying with the powerful heroine who’s supposed to be in control while she pays lip service to surrendering one’s self. Princess Diana is little more than a superpowered Phyllis Schlafly redirected at masculinity.

Rather than roll over for power (give up the “phallus”), I’d rather see boys (and girls) identifying with Carol Clover’s “Final Girl” in slasher films, the last remaining character to face off against the monster (e.g., Halloween’s Jamie Lee Curtis):

If the act of horror spectatorship is registered as a “feminine” experience — that the shock effects induce bodily sensations in the viewer answering the fear and pain of the screen victim — the charge of masochism is underlined. [Not that the male viewer doesn’t also take on a “sadistic” identification with the killer, she adds.] It is only to suggest that in the Final Girl sequence his empathy with what the films define as the female posture is fully engaged, and further, because this sequence is inevitably the central one in any given film, that the viewing experience hinges on the emotional assumption of the feminine posture. [p. 105, Clover]

Clover refuses to call identification with the Final Girl feminist, because of the many reductive psychoanalytic assumptions that have been a hallmark of feminist film theory: she is “a male surrogate in things oedipal, a homoerotic stand-in, the audience incorporate; to the extent she ‘means’ girl at all, it is only for purposes of signifying phallic lack, and even that meaning is nullified in the final scenes [where she picks up a ‘phallic tool’ and inserts it into the killer].” [p. 98] This essay is long enough already, so I’ll resist the urge to debate the issue of just how masculine the Final Girl is or whether she’s a good feminist role model. Clover sees androgyny as a problem, whereas I agree with Gramstad that it’s the goal. But irrespective of which position one might take, the Final Girl is certainly heroic: with great resolve and ingenuity, she resists the urge to give into a nearly unstoppable malevolent force that often is in obedience to a “loving” maternal authority (the dead mother’s voice). Against matriarchal or patriarchal domination, my heroes fight for self-determination.

Wonder Woman and the Femme Fatale

The femme fatale […] tells the truth about sexual relations. It, in fact, is about male fear of Woman, not male hatred of Woman. The femme fatale shows in her supernatural kind of power that Woman is ultimately unknowable, not only to man, but to herself. Most feminists today, obsessed with success and the career world don’t want to think that Woman has any special connection to nature by virtue of her reproductive apparatus. I myself feel that when the femme fatale is thrown out of the canon of modern popular culture, we lose an enormous amount of the voltage between the sexes that made some of the great films so powerful in the studio era. The origins of the femme fatale are going all the way back, really, to pre-history, the goddess cults of antiquity. We have myths like that of Medusa [and] the succubus […]. There are just so many examples of these images world wide that I have to ask how could they possibly be coming from false social indoctrination? Surely these vampire motifs are being generated automatically in culture after culture around the world by the basic facts of male-female anatomy. That is, that every time a man has sex with a woman he is approaching, again, his site of origins. Therefore, there is always subconsciously a fear that as he puts his essence (as a sexual being), his erect member, into the body of a woman … why, she might take it and he might never get it back again. Or he might, by some weird, nightmarish process, begin to shrink down to a baby again and be re-absorbed into the feminine matrix. [Camille Paglia, approximately 1:40:00 into her audio commentary for the Basic Instinct dvd]

Safe to say, that’s not the majority opinion on the femme fatale among feminists. Nor do too many claim Paul Verhoeven and Joe Eszterhas’s Basic Instinct as their favorite movie – at least, Paglia’s the only one I could find. Nevertheless, I think she’s right (and she was the premier counter-intuitive intellectual culture-muncher until Slavoj Žižek cock-blocked her). The standard line of thought agrees that the femme fatale is the dangerous representation of sexual feminine mystique, but objects that it exists as spectacle for, and to be put into its narrative place by, the sadistic gaze: the willfully transgressing female, exerting her independence (frequently depicted as criminal), is brought under control by the dominating male power whereby feminine chaos is restored to patriarchal order. Likewise, in Wonder Woman #28, Cheetah, Eviless and the other femme fatales, who dare assert their freedom, have to be captured, punished and possibly reprogrammed by the dominant order (matriarchy or the mother’s voice in place of the patriarchy). Generally dismissive of the objectifying male gaze [1], Paglia chooses to focus on the fact that where there’s fear of female power, there is an acknowledgement of that power. As she expresses in “No Law in the Arena” (a personal manifesto), the code of Amazonism is that this power should be used in resisting the suppression of woman’s free will. [p. 40, Paglia] No wonder her admiration for Sharon Stone’s Catherine. The character heads her own little Amazonian secret society, but would not be welcome on Paradise Island.

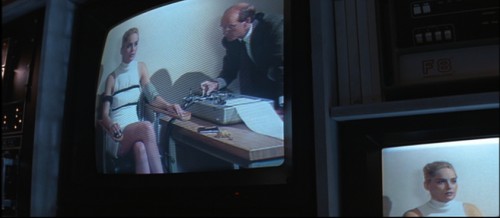

Catherine is Barbara Creed’s monstrous-feminine (the abject representation of the pre-Oedipal mother)[2] in the role of the serial killer. She is more symbolic of her gender than her androgynous brethren are theirs (e.g., Jason, Norman). Her vortical vagina is the locus of her power, devouring all proximal sexual energy to be re-directed as she desires. Just the sight of it turns the lawful masculine order into a sweaty mess. Verhoeven seems to have filmed her with gaze theory in mind. She controls when and where the masochistic hero, Nick (Michael Douglas), sees her naked. And if she’s being spied on voyeuristically, she directly returns the gaze with a cold, calculating stare. Nor does a panoptical vantage point save the voyeur from her gaze. Loving the penis, her weapon of choice isn’t the castrating blade, but a true fetishistic analog, the ice pick. And what’s the first thing to be penetrated in close up? The male eye.

Basic Instinct is one of the purest expressions of the masochistic aesthetic’s double bind in film noir:

If the male spectator identifies with the masochistic male character, he is aligned with a position usually assigned to the female. If he rejects identification with this position, one alternative is to identify with the position of power: the female who inflicts pain. In either case, the male spectator assumes a position associated with the female. In the former, he identified with the culturally assigned feminine characteristics exhibited by the male within the masochistic scenario; in the latter, he identifies with the powerful female who represents the mother of pre-Oedipal life and the primary identification. [Gaylyn Studlar, quoted in Williams, p. 131]

Catherine is the cool figure one wants to identify with and fantasize about. By telling the story from Nick’s perspective as the investigating police detective, she is kept mysterious and the viewer is forced to identify with his pathetic, failing attempts at trying to maintain some semblance of machismo control. One wants to be punished by her for his feeble-minded conformity. Her sadistic control is a fantasy of resistance against both social and cinematic domination. In this way, Basic Instinct is in the long line of crime films that use the criminal as a symbol for freedom (e.g., Scarface, Bonnie and Clyde). Catherine does the binding and escapes punishment. Any attempt to contain her, by either the patriarchy’s representative or one of her Amazonian sisters, results in that person’s death and/or psychological obliteration.

I submit that the flaunting of so many characteristics commonly associated with patriarchal cinema makes Basic Instinct feminist, while the androgynous, or trans-gender, identification (sadistically with Catherine, masochistically with Nick) serves as a critique of the more reductive versions of gaze theory. As a celebration of Catherine, the film provides a counter-narrative to Wonder Woman, where Villainy Inc. is given its due as the proper (anti-)heroes of the story. If you can’t resist the lasso, as Catherine does the polygraph, then make it serve the resistance.

Conclusion

I went into the Marston’s last issue figuring I’d be bored, and came out with a newfound appreciation of just how ideologically noxious a well-intentioned, goofy superhero book could be. He evidently lived in a world of inverted qualia. The book remains a real chore to get through, but it’s always fascinating to me when a liberal finds totalitarianism a utopian expression of his or her core values, feminist or otherwise. Maybe Wonder Woman will inspire some little girl to shatter dictatorship’s glass ceiling when she grows up. That would be real progress.

Footnotes:

[1] “[S]exual objectification is characteristically human and indistinguishable from the art impulse.” [p. 62, Paglia] To which, I say, “amen, sister.”

[2] Creed has an entire book devoted to the subject, The Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis, but I’ve only read her analysis of Ridley Scott’s Alien in “Horror and the Monstrous-Feminine: An Imaginary Abjection.” Like the general consensus on the femme fatale, this representation would seem to only serve the patriarchy:

This, I would argue is also the central ideological project of the popular horror film – purification of the abject through a [quoting Julia Kristeva] “descent into the foundations of the symbolic construct.” [p. 46, Creed]

Although, I could see a pro-feminist interpretation of Lars von Trier’s Antichrist using this approach pretty much writing itself.

References:

Alder, Ken, “A Social History of Untruth: Lie Detection and Trust in Twentieth-Century America” (2002), a .pdf download from author’s website.

Clover, Carol J., “Her Body, Himself: Gender in the Slasher Film” (1987/1996) in The Dread of Difference: Gender and the Horror Film, Barry Keith Grant (Ed.): p. 66-113.

Cox, John, “The Evolution of Surveillance: Security Comes with a Cost” (2009) on the author’s website.

Creed, Barbara, “Horror and the Monstrous-Feminine: An Imaginary Abjection” (1986/1996) in The Dread of Difference: Gender and the Horror Film, Barry Keith Grant (Ed.): p. 35-65.

Gramstad, Thomas, “The Female Hero: A Randian-Feminist Synthesis” (1999) on POP Culture: Premises of Post-Objectivism.

Jones, Gerard, Men of Tomorrow: Geeks, Gangsters and the Birth of the Comic Book (2004)

Mulvey, Laura, “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema” (1975/1986) in Narrative, Apparatus, Ideology, Philip Rosen (Ed.): p. 198-209.

Paglia, Camille, “No Law in the Arena” (1994) in Vamps & Tramps: p. 17-94.

Solanas, Valerie, S.C.U.M. Manifesto (1968) on UbuWeb.

Williams, Tony, “Phantom Lady, Cornell Woolrich, and the Masochistic Aesthetic” (1988/2003) in Film Noir Reader (7th Edition), Alain Silver & James Ursini (Eds.): p. 129-143.

Wood, Robin, “Fascism/Cinema” (1998) in Sexual Politics & Narrative Film: Hollywood and Beyond: p. 13-28.