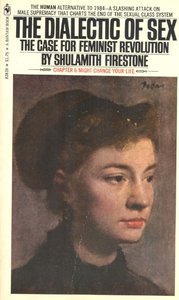

“Just as the end goal of socialist revolution was not only the elimination of the economic class privilege but of the economic class distinction itself,” wrote radical feminist Shulamith Firestone, “so the end goal of feminist revolution must be … not just the elimination of male privilege but of the sex distinction itself: genital differences between human beings would no longer matter culturally.” This same understanding exists, if in a less cogent form, in Paul’s letter to the Galatians. Galatians 3:28 makes the oft-quoted assertion, “There is neither Jew nor Gentile, neither slave nor free, nor is there male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus.” Following as it does several denunciations of a virtue that appeals to law rather than spirit, this statement of universality is not lightly thrown out, but rests on Paul’s core conception of salvation (“conception” being a key word).

“Just as the end goal of socialist revolution was not only the elimination of the economic class privilege but of the economic class distinction itself,” wrote radical feminist Shulamith Firestone, “so the end goal of feminist revolution must be … not just the elimination of male privilege but of the sex distinction itself: genital differences between human beings would no longer matter culturally.” This same understanding exists, if in a less cogent form, in Paul’s letter to the Galatians. Galatians 3:28 makes the oft-quoted assertion, “There is neither Jew nor Gentile, neither slave nor free, nor is there male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus.” Following as it does several denunciations of a virtue that appeals to law rather than spirit, this statement of universality is not lightly thrown out, but rests on Paul’s core conception of salvation (“conception” being a key word).

The erasure of distinction between Jews and Gentiles is what Paul discusses back in chapter 2; it is a letter to a church, after all. But the other two distinctions, the ones involving the inferior classes of slaves and women, not to mention children, are addressed simultaneously in the fourth chapter. And, as feminists did almost two millennia afterward, he rooted this hierarchy in the system of inheritance that forms the core of patriarchy. A child of a wealthy man is like a slave until coming of age, Paul reminds the Galatians, and the life and crucifixion of Christ means that, in the eyes of God, nobody is truly a child nor a slave any longer. He then moves on to expressing his concern for them, and compares himself to a mother in labor.

Paul continues very deliberately to pursue the childbirth metaphor. He offers two mates of Abraham as models– one slave, one free. Each bears a son– the first, Hagar, “of the flesh,” the second, Sarah, from “a divine promise.” Sarah is the mother of Isaac, a patriarch of Israel, but Hagar, the mother who is a slave, is described by Paul as the mother of the earthly Jerusalem, which lives in slavery (under the Law and under the Roman heel).

An interesting parallel to this (and to other Biblical pairs of sons) exists in Mark Twain’s Pudd’n’head Wilson, in which two children, one slave and one free, are switched by the mother of the slave child at birth. The free child who becomes a slave is hardworking and noble, while the slave child who becomes free is vicious, irresponsible, and, eventually, a murderer. The use of fingerprints in solving the murder might argue for a racial theory of behavior, but this conclusion is derailed by the introduction of a pair of black European twins into the story, who are falsely accused of the crime committed by the almost-entirely Caucasian son of the slave woman. The system of power and paternity (i.e. patriarchy) on which the entire system depends becomes almost a character at the end of the novel, when the murderous son has his slave status reinstated and is sold into the living hell known as “down the river.”

But, lest it be deemed a fit and just law, it is also this patriarchy that leaves the slave mother sorrowful in repentance, and the freed son lonely in his enfranchisement, without a secure sense of himself. That such an oppressive law would be seen by Paul as identical with the system of inheritance is made explicit in chapter 27 of Galatians, in the verse from Isaiah he quotes to decree all the faithful to be the free children of Abraham’s infertile wife Sarah.

Be glad, barren woman,

you who never bore a child;

shout for joy and cry aloud,

you who were never in labor;

because more are the children of the desolate woman

than of her who has a husband.

Firestone’s major work, The Dialectic of Sex: The Case for Feminist Revolution, focused a great deal on the central necessity of relieving women of asymmetrical duties in regard to childbirth and child-rearing. “A mother who undergoes a nine-month pregnancy is likely to feel that the product of all that pain and discomfort ‘belongs’ to her,” she wrote; also, “If women are differentiated only by superficial physical attributes, men appear more individual and irreplaceable than they really are.” Freedom, both for Paul and for Firestone, rests not on the acts of privileged individuals, but of erasing the very structure of privilege. That one comes through faith and one comes through revolution is not a minor consideration, but in both cases, as with Twain, the contradictions on which the structure rests must be brought to light in order to begin the creation of a new reality.