This is part of a roundtable on The Drifting Classroom, and also part of the October 2011 Horror Manga Movable Feast.

My apologies for the dicey quality of the scans.

____________

“School is a totalizing [pre]occupation in Japan,” writes anthropologist Anne Allison in her 1996 monograph Permitted and Prohibited Desires: Mothers, Comics, and Censorship in Japan.

Allison’s subtitle doesn’t mention either children or schools, but in some ways that only emphasizes her point. For Allison, the school in Japan in the 70s, 80s, and 90s was totalizing not just for students, but for society as a whole; you didn’t have to point to it specifically, because it was everywhere. In postwar Japan, Allison argues, “adult careers depend almost entirely on the schools children attend, which in turn depend almost entirely on the passing of entrance exams at the stage of high school and college.” The result is, according to Norma Field, a “disappearance of childhood in contemporary Japan.”

For Field (whom Allison quotes), the disappearance of childhood refers specifically to the manner in which children are saddled with the (literal) burdens of adulthood — the way that, as Allison says, children are forced to “pick up early the connection between their success as students in the routines of study and their future success as adults in the networks of work and social status.” Rather than adults being responsible for children, kids are, in this scenario, made to be responsible for adults.

Allison, however, complicates this relatively straightforward point. Reading through the book, it becomes clear that if childhood in Japan has disappeared, it is not just because children have been forced to become adults, but because adults determinedly cling to childhood — particularly, Allison argues, to the (often sexualized) ideal of intimacy with their mothers. Following the work of Japanese psychoanalyst Heisaku Kosawa, Allison suggests that the Oedipus complex does not adequately describe socialization in Japan. Instead, Kosawa proposed a complex based on an Indian myth known as the Tale of Ajase. In the story, Ajase and his mother, Idaike, both attempt to kill each other, fail, and then forgive each other. According to Allison, the differences between Oedipal and Ajase models are:

(1)the role played by the oedipal mother is primarily passive…whereas the role of Ajasean mother is active, not limited to or even focused upon (sexual) desire, and pivotal to the plot. (2) The father’s role is central in the oedipal model, and patricide leads to the boy’s inability to assume manhood. In the Ajasean myth, by contrast, the father barely figures at all and has no primary role in the son’s development to manhood. (3) The oedipal model is based on a clear-cut set of rules that operate on the threat of violence…. The Ajasean model is organized more along the lines of interpersonal relations that depend on mutual forgiveness and empathy. (4) In order to achieve manhood, the oedipal boy must accept the exclusiveness of his parents’ sexual bond and separate from both to establish himself as an individual, whereas the Ajasean boy needs to remain bonded with his parents, particularly his mother, but with the newly mature attitude of mutual respect.

__________________

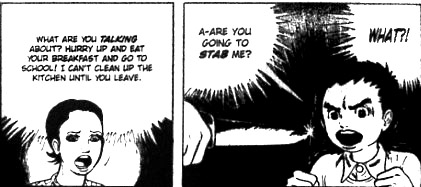

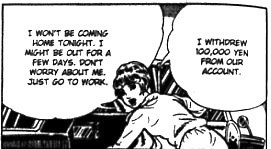

You don’t have to read far into Kazuo Umezo’s 1970s horror manga Drifting Classroom to find the Ajase complex. In fact,the opening sequence of the manga is a pitched battle between the protagonist, Sho, and his mother. His mom wants Sho to be more responsible about his schoolwork. Sho wants to stay focused on childish things. The most telling sequence, perhaps, is this one.

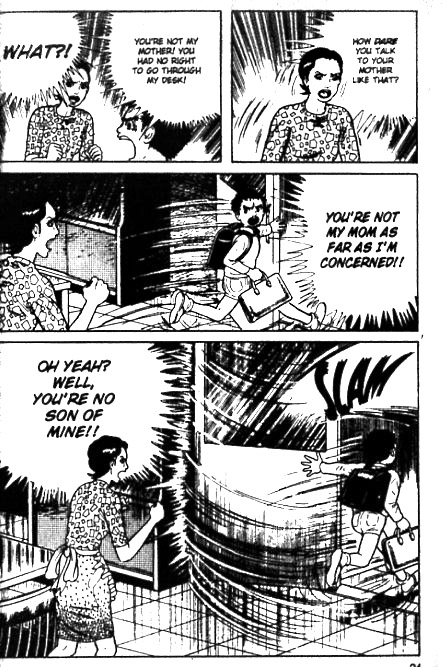

That’s castration fear, no doubt — but it’s a castration fear centered on the mother, not the father. And, moreover, it’s a fear not of being unmanned, but of being forced to become a man at knifepoint. Sho’s mom has thrown out his old, banged up marbles. She’s cutting away his childhood and,simultaneously, his intimate relationship with her. He reacts less like an angry son and more like a spurned lover…as indeed, does she.

Sho races off to school. He insists he’ll never return; his mom tells him never to come back. And they both get their wish. His school building, with Sho and all his classmates inside it, vanishes into a post-apocalyptic future, never to be seen again. The teachers quickly go insane and murder each other, and the sixth-graders, with Sho leading them, are left to take on the adult responsibility of caring for the little ones and preventing civilization from sliding into the abyss.

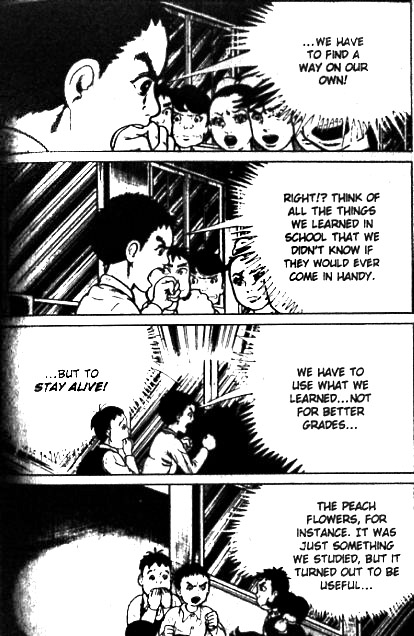

The link to Allison’s analysis of childhood in Japan couldn’t be much clearer. What you learn in school determines your future prospects; so what Sho and his classmates learned in school determines their fate in the future.

Indeed, often the post-apocalypse seems designed as a kind of corporate team-building exercise — a series of arbitrary hoops providing for sequential infantilizing achievements. The students face difficulty after difficulty; find water, choose a leader, jump over deadly ravine, overcome personal differences, learn to remove an appendix, kill deadly mutant starfish. The adult future, like the childhood past, is an eternity of adrenalin-fueled testing.

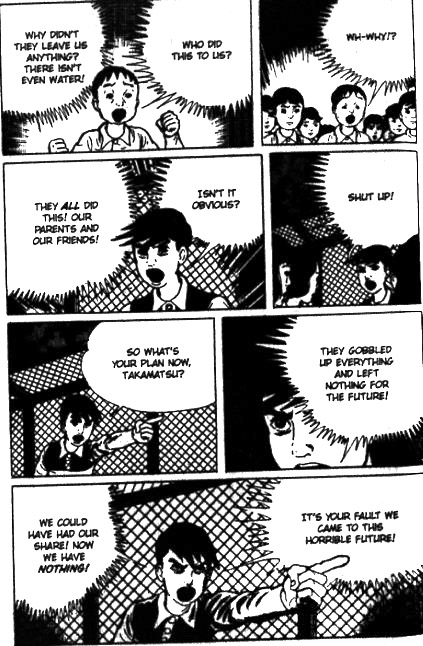

In part, this is definitely meant to be a nightmare vision — even, perhaps, a critique. As Otomo (one of the sixth-graders) shouts late in the series, “They all did this! Our parents and our friends! They gobbled up everything and left nothing for the future.”

The complaint is couched in ecological terms, but the imagery suggests other meanings. Otomo’s eyes are sunken and his mouth gapes like a death’s head; he looks prematurely aged. Behind him the school fence looms like a cage. It’s not just the world that has been exploited and used; it’s the kids themselves. Trapped and harnessed, their childhood is the price for Japan’s post-war economic miracle; it’s their labor that overcomes the apocalypse.

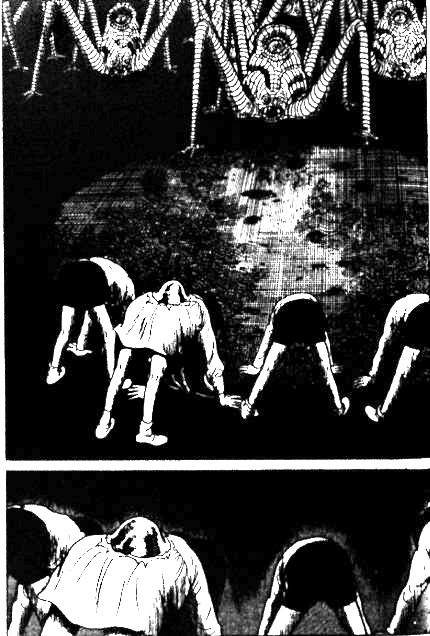

Umezu’s revulsion at what Japan does to its children powers the manga’s most viscerally disturbing episode. After eating mutant mushrooms, many of the children begin changing. First they start worshiping a hideous idol.

Then they change physically. In perhaps the books most chilling line, one girl who is making the change tells her classmate, “You were my best friend. But in our world there’s no such thing as friends.”

Tenderness and intimacy are replaced by a staring eye; the Panopticon banishes love. Umezu later reveals that the mutant creatures are literally humanity’s children; abandoned twisted abortions. Cast out of the family, they have neither love nor loyalty; even language has become, as they say, only a ritual. They communicate instantly in a kind of hive mind,and when they find that one of their fellows has hidden something from them, they fall upon it and kill it instantly. The children/mutants turning into these creatures stand bent over in rows in a perfection/parody of regimented good behavior. The monsters are, in short, an apotheosis of biopower — shaped to meet the exigencies of their society, self-watching, self-regulating. One of them even boasts that they are superior to humans because they learn more quickly. They are the children of the future; the ideal nightmare progeny of Japan, the test-takers who made themselves over as the test required, and then crawled out to conquer the world.

The mutants are certainly one vision of Japanese children, but they’re not the only one. If some of the kids worship their one-eyed watcher, others worship a less terrifying authority — mother.

When I say “worship”, I mean literally worship; the kids set up a bust of Sho’s mother as an idol to remind them of home and watch over them. And she does a fairly good job; at various points in the manga, Sho calls to his mother for help, and back in the past, she hears him and figures out ways to get him the aid he needs. Once, she secretes a knife in a hotel wall so that, in the distant future, Sho can find it and use it to kill a murderer. In another incident, she hides antibiotics in the body of a dead baseball player. Sho finds the guy’s mummified remains and is able to stop an outbreak of the plague among the school kids.

Sho’s reconciliation with his mom recalls the Ajase myth; the tension between mother and son is resolved by guilt (Sho’s mom feels really, really bad that the last thing she said to him was that he should never come home), grief, and reconciliation.

It also, and not coincidentally, echoes the idealized Japanese relationship between a mother and a student. In Japan in second half of the twentieth century, Allison says, men were largely absent from home, working long hours, engaging in de-facto-required after-work socializing, and commuting extended distances — sometimes up to three hours one way. With the husbands out of the picture, mothers were expected to stay home and devote themselves to their children’s (especially their sons’) education. It was up to mothers to fit boys to become the next generation of (productive) workers and (absent) fathers.

Allison argues that mothers did this in two ways. First, they enforced and extended the behavioral regime of school — insisting, for example, that children had to maintain a school-like schedule even over the summer, and pressuring them to work hard at their studies, as Sho’s mom does at the beginning of the manga. At the same time, though, Allison said, women also “offer the child a measure of emotional security and intimacy with which to survive these demands.” This can take the form, Allison says, of “treats, indulgences, and creative pleasures.” Thus, at the conclusion of the manga, Sho receives from his mother what is essentially the world’s biggest care package, an orbiting satellite filled with gifts, a mother’s love sent forward in time to make the future bearable for her man-child.

Mother’s love, then, makes schoolwork not just work, but pleasure. Turning one’s life into school isn’t (or isn’t just) an early separation from the mother (as in the first fight scene between Sho and his mom.) It’s also a profound union with the mother. When Sho is in the school in the future, he is separated from his mom, but his bond with her is, at the same time, more perfect, more blissful, more full, than it has ever been. He holds her affections now more than ever. His father (like Ajase’s father) is completely superfluous.

In her book, Allison talks at length about the prevalence of mother/son incest urban legends in Japan. These always take the same form; a son, studying for his exam, is distracted by sexual thoughts. His mother, to help him focus, decides to begin an affair with him. Both mother and son enjoy the affair immensely — and the boy does well on his exams. These stories, Allison says, proliferated especially in the late-1970s, not long after Drifting Classroom was published. Given that, the scenes in the book which feature Sho’s mom and Sho’s classmate, Shinichi, conspiring together secretly in a hotel room take on a very suggestive air. Sho’s mom is helping Sho succeed at school by disguising herself and then going off to form an (intimate) bond in a hotel room with Shinichi, Sho’s double. School and sex and mother and the future are all wound together in a productive cathexis of anxiety and pleasure.

On the one hand, then, Drifting Classroom rejects Japan’s totalizing preoccupation with school. It condemns the society which makes of its children little adults, laying waste to the present the better to build a wasted future. But the flip side of the cleansing nightmare is a less pristine daydream. The terror, the grief, the piles of dead children, each more imaginatively mangled than the least — this is not the price of pleasure, but the pleasure itself. The forced adulthood and the hardship are the path to, and therefore inseparable from, the intimate love of mother.

In the last pages of the manga, Sho’s mother looks through the window and declares, “We have to work for a brighter future…a future where our boy is so brave…and where he’ll grow up strong and survive….not here, but somewhere in the future.” As she says this she sees her son and his friends running amidst the stars, through heaven. In some sense, it’s a happy ending, a tribute to the power of a mother’s love to illumine even the most terrible future. But it has a darker edge as well. For surely the manga shows that, in Japan as in the U.S., when we erase our children’s present the better to love their future, school — and not just school — will be horror.