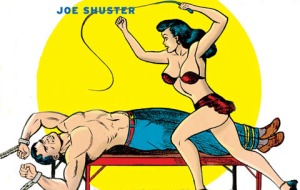

Of all the images to feature in this month’s review of Brad Ricca’s Super Boys, The New York Times went with one of “the kinky illustrations Shuster was reduced to doing for sleazy magazines in the mid-1950s,” specifically one that, according to editor Peter Keepnews, “looks for all the world like Lois Lane preparing to whip a trussed-up Superman.”

Craig Yoe had the same idea, choosing an even more overt image for the cover of Secret Identity: The Fetish Art of Superman’s Co-Creator Joe Shuster: Lois in high heels and underwear not preparing but full-on whipping a chained and bare-chested Clark. The Man of Steel shattered identical chains on Action Comics every month, but this Shuster illustration is working toward a very different climax.

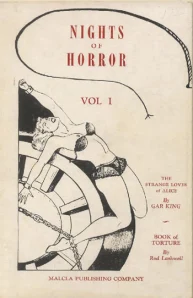

Yoe’s title is a bit of a dodge though, and Keepnews’ “kinky” is no better. Yoe reproduces Shuster’s 1954 illustrations for Nights of Horror, a typo-strewn black and white cranked out of Shuster’s neighbor’s basement, but unlike almost anything else related to superheroes, this is not “Fetish Art.” Zorro dressing up in a mask and cape to keep his sword erect? That’s a fetish. Hooded men assaulting bound and weeping women? Frederic Wertham termed it “pornographic horror literature.” I call it rape and torture.

Craig Yoe is less coy between the covers: “These BDSM (bondage-discipline dominance-submission sadism-masochism) tales were an equal opportunity employer. Women were tied up, whipped, and spanked, but could eagerly be the tie-ers, whippers, and spankers, too.”

Well, not exactly “equal.”

Of Shuster’s 108 illustrations, I count seventy-one that depict women dominated by men. The reverse occurs nine times. Add another nine scenes of women dominating women for a grand total of eighty female victims. Shuster draws only one incident of a man dominating another man (with a woman as the primary focus, so the men are not—gasp!— a homoerotic pairing) for a total of ten victimized men. Check my math, but an eighth is a lot less than “equal.”

Most common torture device: a whip. Eighteen of the twenty-two appearances are used against women. Other devices used to torture women (in alphabetical order): air hose, alligator pit, ball and chain, cactus, chains, corset, electric wire, fingernails, gun, hairbrush, hot poker, hypodermic needle, iron maiden, knife, paddle, paddle machine, spiked bed, spiked gloves, switch, and water hose. Additional techniques to dominate women: champagne, hypnotism, marijuana, opium, and polygamy.

Men are whipped, spanked, paddled, clubbed, and one anticipates the removal of a toe. Three more display submission by kissing a woman’s shoe, kneeling with a tiny chain attached to his ear, and (my favorite) serving a woman breakfast in bed.

The nudity is almost exclusively female. Only four illustrations feature clothed women. Another ten reveal partially exposed underwear, usually from a forcibly raised dress hem. Some seventy-one (by far the standard) are women in nearly identical see-through bras, panties and those mid-thigh pantyhose and garter belt contraptions I’ve never really understood. The remaining twenty-three or so feature full or partial nudity, which usually means exposed breasts, but occasionally buttocks, and very rarely a vaguely drawn crotch. So vague, in fact, as to seem sexless. (Women were not, to the best of my very limited my knowledge, shaving their pudenda in the mid-50s).

The one image of full male nudity is also oddly sexless—or at least gravity-defying. The more disturbing anatomical features are the women’s freakishly tiny hands and feet. And their high-heels which appear to be permanent growths of their otherwise naked bodies.

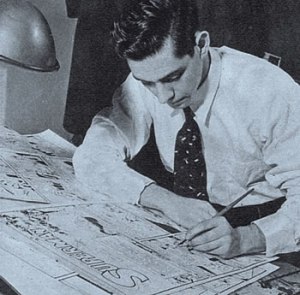

Stan Lee (he wrote Yoe’s introduction) looks at these pictures and sees a “disillusioned and desperate” Joe Shuster “forced to accept commissions to draw what amounted to S&M erotic horror books.” Although the unemployed Shuster was financially desperate in 1954, his arrangement with Nights of Horror was sounder than his one with DC Comics.

He was paid $100 for each of Nights of Horrors issue, for a total of $1800. Less than twenty years earlier, his bosses at DC had written him a check for $130, which he split with his partner Jerry Siegel. That was in exchange for the permanent, multi-million dollar rights to Superman. Shuster drew an average of six illustrations for each Nights of Horror. That’s a page rate of just over $16. He and Siegel were splitting $10 a page back in 1938. DC grudgingly raised it $15 when the Action Comics spin-off Superman sold 900,000 copies the following year. Nights of Horror boasted a print run of only 1,000, including the 2,650 backlog confiscated in a book store police raid.

By any accounting system, Nights of Horror was a far more financially ethical employer than DC.

As far as disillusionment?

Shuster’s Nights of Horror illustrations are not hack work. He’d didn’t doodle a half dozen half-hearted sketches in exchange for that week’s grocery money. Despite his failing eyesight (what finally pushed him out of comic books in the late 40s), these pages have been pored over. The detail is at times lovingly and so disturbingly precise—reminiscent of Robert Crumb’s own obsessively rendered female figures of the following decades. The best here easily exceeds the rawer material he rushed off for Action Comics. Joe was getting more out of Nights of Horror than a paycheck.

I don’t care to imagine the nuances of Shuster’s sexual life, but I will guess that it was primarily a solitary activity. Yoe documents his preference for tall women (he was short), and his brief marriage to a former Vegas showgirl in 1975 (they look the same height in their wedding photo). Superman provided his best pick-up lines. According to biographer Gerard Jones (I haven’t read Ricca yet), he would hang out at soda fountains and hand girls (the tall ones presumably) sketches of his Man of Steel before asking them out. At least one fifteen-year-old said yes. Shuster was 25 at the time.

He was forty in 1954, and working alone. His studio of assistants dispersed after he and Siegel lost their lawsuit against DC in 1948. Nights of Horror was some of the only art he’d sold since Superman. Although not paneled like a comic book, the illustrations are often sequential and depict narrative movement. Two sequences conclude with heroic rescues of female victims by Superman-like saviors. A sadistic film producer collapses from a detective’s bullet, and a bearded cult leader succumbs to a punch on the jaw. Only one woman defends herself. She rushes at her captor with a knife and seems to have the upper hand—briefly. She’s bound as he whips her on the next page.

I’m going out on a limb here and guessing that Shuster did not collaborate with a model for these illustrations. The stock repetition of body type and undergarments suggests an internal, idealized projection, one with rounder hips and thighs than any of today’s anorexic supermodels. But even when a live human being posed in front of his canvas, Shuster always saw what he wanted to see. A teenaged Jolan Kovacs answered his 1935 ad for a model in the Cleveland Plain Dealer. He wanted to practice his Lois Lane sketches before retooling Superman for a new round of newspaper syndication submissions. Kovacs couldn’t fill out her sister’s baggy swimsuit, but Shuster’s sketches do not share the shortcoming. The picture of Scarlet Pimpernel actress Merle Oberon in his head was bigger than the breathing woman before his eyes.

That didn’t stop him from asking Kovacs out on a date. Nothing much came of it then or ten years later when he asked her to the National Cartoonists Society’s costume ball. She wanted to come as Lois Lane, but Shuster and Siegel were in the process of losing their lawsuit. But Joanne (she changed her name for her modeling career) and Jerry (he attended the ball too) were very happy to see each other again. A few months later they were married. It was a City Hall event, so Shuster didn’t have to stand up and mumble through a best man’s toast. Six years after the ceremony, Joe and his Superman partner were done with each other, and Joe was drawing S&M for his neighbor’s underground porn pulps.

I can identify only six of the 108 illustrations that depict scenes of consensual sex. (Call me Puritanical, but I am eliminating the reefer-smoking Jimmy Olsen in the early stages of pot-fostered date rape.) Of the six, two are heterosexual, and four lesbian. There are twice as many lesbian images of women dominating other women, but even in those the content is less violent than elsewhere. Nights of Horror lesbians tend to spank with hairbrushes and bare hands rather than whips or switches.

The lesbian imagery is, of course, for male consumption. Which apparently eliminates the need for other reader-titillating taboos. Twice the girl-on-girl action is interrupted by a man bursting through the girls’ closed door—the thinly disguised desire of the perceived reader.

Even when the male presence isn’t literalized, Nights of Horror foregrounds its voyeurism. Only one page in the collection depicts a lone figure, and she’s not preening just for her mirror. Other pages are more overt: an eye in a peep-hole, a man leering through a window, a grinning boy at the corner of the frame watching a spanking. That’s us.

Shuster draws himself too. A painter stands before his canvas, brush in hand, staring at his model (one of the very few women not in high heels). The sketch on the canvas is nearly identical to the actual model. They are made of exactly the same black-on-white pen strokes. Yoe includes a caption:

“At last he had her posed to his satisfaction.”