This post is cross-posted from over at The Middle Spaces.

______

Over the Thanksgiving Weekend, like a lot of people we know, my wife and I binge-listened to Serial. Serial is a podcast by the producers of This American Life, an episodic exploration of a murder case from 1999 that seems to have more questions than answers, but that is nonetheless addictive. So addictive, in fact, that Slate.com has its own podcast deconstructing each episode of the original podcast and indulging in a little speculation, because those folks couldn’t stop taking about it. We listened to those as well in order to bolster our own fodder for discussion. If you don’t know what Serial is, I highly recommend stopping whatever you are doing and going to go listen to it.

It bears mentioning that despite what is to follow in this post about Serial as a narrative, it nonetheless is a story about real people whose lives have been forever changed by that murder and the subsequent trial. As the folks on the Slate podcast have mentioned many times, there is a tension that a listener feels—or should feel if they have any hint of compassion and intelligence—between enjoying this story, getting sucked into the pleasures of a mystery, and understanding that this pleasure is at the expense of actual human lives.

And I think it is from that realness that the question that preoccupies many fans of the show seems to rise: how will it resolve? As a “real-life” story there is no promise of resolution. As an example of story-telling, we expect it to have one. Does Sarah Koenig (the reporter/narrator) already have an end in mind that she is tantalizingly building towards, or is this a serial the way serials have been most frequently and classically constructed: as it goes along—prolonging the narrative as long as it can be drawn out? Sure, in the case of a TV show or a comic book series, in other words, popular serialized fiction, longevity is determined by continued popularity, but in this case, the question is: how much evidence and human interest and non-litigious speculation can be drawn from the story of Adnan Syed and the murder of Hae Min Lee? And how can Koenig do this in as non-exploitative a way as possible, while still making a radio show that relies on the audience’s attraction to the sensationalism of murder and the intrigue of a painful mystery?

To further complicate things, the broadcast of the show itself can and has influenced the very investigation it enacts (and has inspired others to take up). The possibility for a so-called “satisfying ending” seems to be simultaneously becoming more possible and less likely.

What is brilliant and a bit subversive about Serial is that by putting a “real-life” story into the frame of a fictional serial, it is critiquing that desire for resolution, shining a light on it as a limitation, a need for artifice rather than simply a requirement of story-telling—framing your signs into a sequence to make them cohere and take a comprehensible shape.

Really, this obsession with the end of Serial (are there really only two episodes left?) has made me want to go back and watch Lost again.

When ABC’s Lost was at the height of its popularity there was a common mantra from its fans (and those who claimed to be fans), that the show had better wrap up all its many plotlines and mysteries, that there had better be answers to all our questions, an explanation for the strangeness and coincidences that drove what appeared to perhaps be a plot, but that was a really a study in characters.

Of course, by now Lost’s unsatisfying ending is kind of legendary. I made some excuses for it when it aired, but really I wasn’t trying to say it was actually good, but that it was as good as you could expect from a show for which the very idea of beginnings or endings were anathema.

Rather, it was my contention (and remains my contention) that the ending of Lost doesn’t matter. The characters on that show were lost when the show started, long before crash landing on that mysterious island, and regardless of the outcome would remain lost, because we are all lost. It is a condition of living.

At least, that was my assertion in a short essay I wrote about Lost at the opening of the 4th season, when the flash-forwards were introduced. And I still agree with it, but the way in which Serial reminds me of Lost has forced me to stop and ask myself about endings again, their value and their artificiality.

The thing about Lost is that each episode and every arc of a season introduces more mysteries than it can solve. Lost takes place on an infinite nesting doll of an island.

I wrote,

“Let’s get this straight, if I were on that island, while I might not be as crazy and driven as Locke, I too would not want to leave. I would be happy to stay on that island with the polar bears, smoke monsters, mad scientists, crazy trap-laying French women, wild boars and electro-magnetic disturbances. When it comes down to it, I do not see how the world of LOST, the universe that is that island, is any different from the world they came from. While the mystery and convolution may be a little more condensed than we are used to. . . [in] our own lives, even without being survivors of plane wrecks on a (not-so) deserted island, have just as much mystery, craziness and convolution. . .It is just easier for us to pretend as if that is not the case, as if we have some kind of control over our environment, when in truth, control is an illusion.”

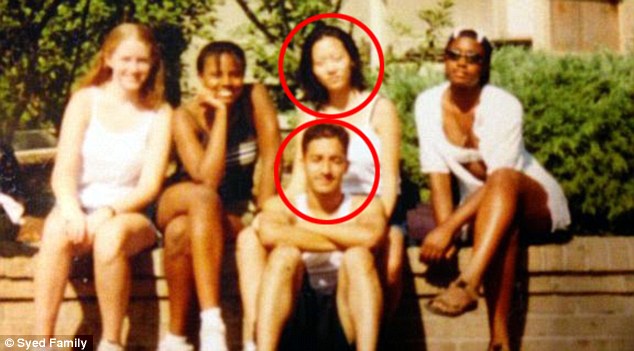

If there is one thing that represents that lack of control in the popular imagination it is the time-worn trope of the unjustly accused and jailed—the hope for redemption. As when the one-armed man is finally caught in the act and Dr. Richard Kimble gets to cease being a fugitive. Of course, it is a lot easier to get a prosecutor to believe your story when you are played by Harrison Ford. When you are in the role of Adnan Syed and you have to play yourself, a Pakistani-American Muslim teenager, it doesn’t work out that neatly.

Lost plays with that trope as well, in the form of Kate, except it upsets the pattern by making her actually guilty of her crime, building sympathy for her through flashbacks, but also undercutting that slightly by showing her ability to be cold and determined. Of course, she’s a pretty white woman, so we don’t begrudge her the deal she gets when the charges are dropped (or whatever it is that happens in Season 5 when she and Jack and a couple of others do succeed at leaving the island for a time), the way some listeners probably begrudge Serial’s Jay—a suburban black kid turned snitch (at best) and false accuser (at worst).

No, it is not through direct comparison of characters or elements of plot that Serial and Lost resonate with one another for me, but through the form—that narrative openness that develops when a serial curls back (and sometimes forward) on itself, expanding in all directions into Gordian knots that resist easy cutting. The latest episode, #10 “The Best Defense is a Good Defense,” just reinforced the comparison in my mind. The look back on Cristina Gutiérrez—Adnan’s defense counsel—played out like those interstitial flashbacks in the TV series, obscuring as much as it revealed and introducing more side characters that not only serve to develop the character in focus through their relation, but begin to take a shape and develop a gravity of their own in the narrative. In this episode, it was the poor Witmans who were taken advantage of by Gutiérrez, and who are embroiled in their own ongoing drama, involving their son being accused of murdering their other son. The case struck me as just sensational enough to qualify for Serial’s recently announced second season.

No, it is not through direct comparison of characters or elements of plot that Serial and Lost resonate with one another for me, but through the form—that narrative openness that develops when a serial curls back (and sometimes forward) on itself, expanding in all directions into Gordian knots that resist easy cutting. The latest episode, #10 “The Best Defense is a Good Defense,” just reinforced the comparison in my mind. The look back on Cristina Gutiérrez—Adnan’s defense counsel—played out like those interstitial flashbacks in the TV series, obscuring as much as it revealed and introducing more side characters that not only serve to develop the character in focus through their relation, but begin to take a shape and develop a gravity of their own in the narrative. In this episode, it was the poor Witmans who were taken advantage of by Gutiérrez, and who are embroiled in their own ongoing drama, involving their son being accused of murdering their other son. The case struck me as just sensational enough to qualify for Serial’s recently announced second season.

The audio recordings that Koenig and her producers use, from the court proceedings, police interviews, etc… from back in 1999 and the days of the trial, reinforce that feeling of being transported back in time—as do the more recent interviews with possible witnesses, friends and family. Interviews that despite being in the “present” of Serial‘s reportage, are nonetheless already nearly a year old, thus confusing the timeline even more. Hearing those voices is crucial to developing these characters. Those voices are so distinct and become more distinct each time we get to hear from them—Adnan’s sharp analysis of his situation and mastery of language tinged with occasional resentment, Jay’s alternately surly and obsequious good manners, Gutiérrez’s lilting aggression.

But there is also a sense of the imminent that has seeped into Serial—like bearded crying Jack begging Kate to go back to the island—the development around the podcast of things like the Slate Spoiler Special podcast about the podcast and the Serial subreddit (which I haven’t visited, because Reddit) is like a possible future reshaping our view of the present. The flash-forward feeling is present in Koenig having to momentarily pre-empt Episode #9 in order to discuss three developments in the investigation that stand adjacent to how the investigation is unfolding in the narrative as she is telling it.

When I wrote “Staying Lost” back in 2008, I said that “I not only don’t care if the mysteries are ‘answered,’ I don’t want them to be. At this point there is no way that any one ‘answer’ or set of “answers” is going to be satisfactory to all fans (or even most fans) of the show, so why bother trying to make one or give one?”

When I wrote “Staying Lost” back in 2008, I said that “I not only don’t care if the mysteries are ‘answered,’ I don’t want them to be. At this point there is no way that any one ‘answer’ or set of “answers” is going to be satisfactory to all fans (or even most fans) of the show, so why bother trying to make one or give one?”

I essentially feel the same way about Serial, except that Serial is about real people, real suffering, and real—ultimately unanswerable—mysteries. It is harder to accept that unknowability when it is more immediate to our lives and not just philosophical musings. Even if Adnan Syed were to be exonerated and set free, it would not necessarily mean he didn’t murder Hae Min Lee, only that there was enough reasonable doubt about it to make it a travesty of justice for him to spend the rest of his life in jail. Even if Koenig could somehow prove that Jay’s lies are obscuring a greater lie about Adnan’s (lack of) involvement, it would not mean that we’d ever necessarily know and understand why he told those contradictory stories either. We’ll probably never know why Adnan’s defense counsel behaved how she did, seeming to botch the case, we can only speculate that it emerged from her illness and her knowledge of her own imminent death. Or, as David Haglund suggested on the Slate Spoiler Special for episode #10, that she was actually incompetent all along and other people enabled her success until her poor accounting and “pitbull” attitude went beyond what could be managed. No matter what happens, Hae Min Lee’s family will still have to live with the unknowability and confusion that surrounds any death, but especially a murder… What answer can effectively “wrap things up” for them?

Allow me to quote from “Staying Lost” one more time:

“I have given up looking for answers. Answers lead us astray. I don’t need, I don’t want Lost to try to answer anything for me, and the day the last episode airs I would be perfectly satisfied to be left with as many mysteries as the show has piled up over its four seasons…there will be no happy endings or easy wrap-ups to this show even if some people get off the island. Hurley will still struggle with madness and Jack will crumble, becoming a version of the wreck his father was when he first went searching for the elder Shepherd in Australia. I don’t know (and I don’t care) what the “secret” is that the Oceanic Six might carry about their “escape,” because there is no escaping (and now we know that what? The secret was that other people were still back on the island? Hardly mind-blowing to the viewers—just goes to show all escape is illusory)…we drift from mystery to mystery and from joyful cannonballs to confrontations with death and we make choices in the dark never sure of the outcome, and with the dread that even with the desired outcome come countless unforeseen consequences that undermine any success.”

I watched Lost like I read Mind MGMT, with a Sontagian resistance to interpretation.

But as I suggested above, it is a lot easier to say I like and want narratives that resist that urge to resolve and provide answers, when that narrative is a fictional one. The tension for Serial is the “true crime” reportage mashed up with the serialized fictional narrative format. It works because life becomes at least momentarily understandable when put into a narrative frame, but ultimately all narratives are fictional—and that hurts (or we can imagine that it hurts) when that narrative involves you and your loved ones.

In my dissertation project, I explore (among other things) the simultaneous spontaneity and serialized nature of identity work. Seriality is built on an on-goingness that is punctuated by spontaneous recalibration of identity based on, not only the accretion of new information revealed in that unfolding, but also in the re-structuring and re-imagining of what has come before, aided in large part by the positional erasure necessary to assert a coherent “I.” Just as Lost isn’t really about the mysteries of an uncharted island, Serial isn’t really about the mystery of Hae Min Lee’s death or the conviction of Adnan Syed, rather they are both about what can be revealed—what we can learn about these characters in the crucible of that setting. We can’t know these real-people-made-characters, but only hope to construct an identity for them that leads to our belief of guilt or innocence, involvement or victimhood, or both.

Back in 2008, I wrote that Lost is a perfectly apt name for the show, “not only because of the physical displacement, but because all the characters were already lost before they ever got on that plane, before they crashed on that island, just as they will be if they get off it, just like we all are.” Serial is also aptly (if a bit generically) named because in that tension between feeling like it could never end and that it must end and satisfyingly so, it has captured the essence of seriality’s appeal. The major difference for me is that it is much easier for me to express a desire to immerse myself in the idea of “lost-ness” when it manifests as a mysterious island with destructive electromagnetic devices, smoke monsters, ghosts and the remains of a cultish scientific agency, and think of the ways in which our lives parallel that strangeness, than it is when that lost-ness involves the intricacies of the criminal justice system, the insidiousness of racial and ethnic bias, the melodrama of teenagers turned deadly and the emotional harm inflicted on those who have to live that convoluted story. Nevertheless, I remain hooked, and when that final episode airs, no matter what it is like, I will treat it like any other episode, an artificial bracket on the messiness of experience lived and retold.

As an addendum, I would like to add that what is not subversive and brilliant about Serial is its handling of race. I know I am risking, taking away from my exploration of the narrative form of the show by ending on this note, but since most of my writing is about race in popular culture, it would not feel right to not at least comment on how it is handled on the podcast. While I do not find it to be as egregious as some online articles I’ve read and browsed (like this one and this one) make it out to be, the dozens of little assumptions and strange ways to frame people’s lives and characters are pernicious in how the typical discourse of race remains insidiously present despite Sarah Koenig’s obvious sympathy for the podcast’s players. When it comes down to it, I have to remember Anita Sarkeesian’s wise disclaimer at the beginning of her Tropes Vs. Women in Video Games videos, “that it’s both possible, and even necessary, to simultaneously enjoy a piece of media while also being critical of its more problematic or pernicious aspects” when it comes to all forms of media I enjoy. Let’s just hope that Koenig’s sympathy leads her to re-think the ways in which she represents these people and frame their situations as these final episodes are recording and moving into future season. The benefit of this being a “true crime” story, however—as a a similarly minded and Serial-obsessed friend said to me—is that unlike a fictional story that requires new canonical material or fan fiction (though I have no doubt there is some Hae Min Lee and Adnan Syed fan fiction out there) there are plenty of ways for listeners to seek out learn a lot more about these people in ways that do not reduce them—if inadvertently—to stereotypes.