A few weeks back I published a story over at the Washington Times about the effect of the closing of Borders on the manga market. Several of the people I interviewed had such great thoughts that it seemed a shame to just use a quote or two. So I decided I’d reprint them all here. Thanks to Shaenon, Lillian, and J.R. for agreeing to let me do this!

I’ve edited down my comments in several places, since they’re the least illuminating parts of the dialogue.

______________

Email interview with J.R. Brown, BL expert and occasional HU contributor.

Noah: Hey JR. I’m writing because I’m currently working on a piece for the Washington Times about the effect of borders closing on manga. I was interested in the post you made on twitter about how this would have a big impact on the availability of BL titles. I wondered if I could ask you a couple more questions about that.

JR Brown: Hi Noah;

More than happy to talk, although I’m not sure how much help I’ll be, since I’m merely a reader with no inside info. The people at Digital Manga Publishing (the biggest standing BL publisher) seem to be quite responsive to academic/journalistic inquires; you could try giving dropping them a line.

My comments were based on 1) statements made by Digital Manga staff on their forum saying that availability of their BL titles in bookstores (as opposed to online / comic book shops / elsewhere) is a significant driver of sales, 2) remarks by DMP and other BL publishers indicating that Borders was a major component of their bookstore sales, and 3) in the Boston area, Barnes and Noble (our only other major chain) does not carry BL titles in its physical stores (the downtown location stocked the Junjo Romantica series briefly after it made the NYT bestseller list last year, but dropped it even before Tokyopop disintegrated). B&N in my area also just carries much less manga generally, with a more specific focus on the best-selling series and new releases biased towards the larger publishers. I have heard that B&N stores elsewhere in the country do carry BL, but even so it appears that they do so less consistently and to a lower extent than Borders did.

We do have a couple of very good local comic shops that carry BL, and of course you can get everything online, but I think the loss of Borders is going to make it less likely that the casual and especially the new reader will come across the books. And of course the same goes for other manga, especially less-popular series and the output of the smaller publishers.

I’ll be happy to take a stab at any questions you have.

Hey JR. That’s super helpful already, thanks.

Here are a couple more questions if you don’t mind…

—Do you know if Borders moved early on into BL sales? And did they help popularize that genre in the US, or at least make it available?

—Have there been any public censorship efforts aimed specifically at BL? My sense is that it’s mostly been self-censorship when the books have become unavailable, but I don’t know for sure….

—Do you think Amazon is unlikely to attract new readers to manga or BL?

JR: Oh wow. A full discussion of all this would be more than I can knock off tonight, but hitting the high points:

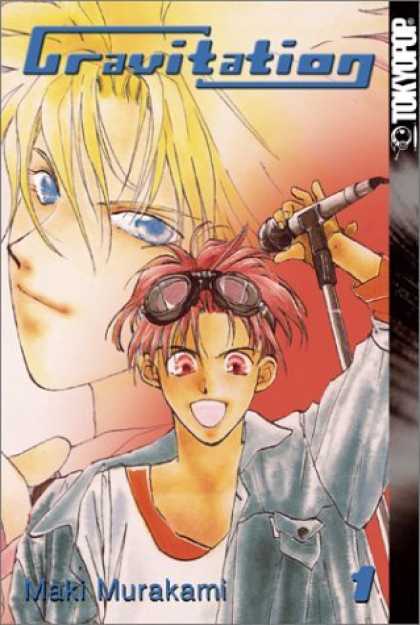

Borders was a major player in manga sales when the format was really taking off in the 2000s, thanks in large part to their graphic novel buyer at the time, Kurt Hassler, who was deeply gung-ho on manga and especially on the idea that girls would buy it. Borders went big and deep into manga in the mid-2000s, just around the time that publishers really started to tackle full-on BL. Several publishers had tested the water with hint-and-innuendo-only BL-esque series previously (and there had been two extremely obscure e-book releases of “real” BL by a tiny company), but around 2003 Tokyopop’s “Fake” and especially “Gravitation” series came out and did extremely well in stores (by manga standards). Borders was a major outlet for Tokyopop’s books (and continued to be so up until their joint demise), so they sold a lot of those series. I don’t know how much Borders supported the first sexually explicit books (from smaller BL publishers like CPM’s BeBeautiful, Media Blaster’s Kitty), but they did carry explicit material a few years later, including Tokyopop’s BLU line once they launched it around 2005. And as I mentioned Borders was apparently a large component of DMP’s BL sales. I don’t know of anything Borders did to popularize BL as such, beyond making the books available, but they definitely did that.

Borders was a major player in manga sales when the format was really taking off in the 2000s, thanks in large part to their graphic novel buyer at the time, Kurt Hassler, who was deeply gung-ho on manga and especially on the idea that girls would buy it. Borders went big and deep into manga in the mid-2000s, just around the time that publishers really started to tackle full-on BL. Several publishers had tested the water with hint-and-innuendo-only BL-esque series previously (and there had been two extremely obscure e-book releases of “real” BL by a tiny company), but around 2003 Tokyopop’s “Fake” and especially “Gravitation” series came out and did extremely well in stores (by manga standards). Borders was a major outlet for Tokyopop’s books (and continued to be so up until their joint demise), so they sold a lot of those series. I don’t know how much Borders supported the first sexually explicit books (from smaller BL publishers like CPM’s BeBeautiful, Media Blaster’s Kitty), but they did carry explicit material a few years later, including Tokyopop’s BLU line once they launched it around 2005. And as I mentioned Borders was apparently a large component of DMP’s BL sales. I don’t know of anything Borders did to popularize BL as such, beyond making the books available, but they definitely did that.

I’m not sure what you mean by “public censorship”. Many BL titles have been censored by the U.S. publisher, either because of legally/morally questionable content (particularly underage characters) or, frequently, to make the material tamer and more acceptable to bookstores. Usually it’s a question of a few panels being retouched, or dialog or character ages changed, but occasionally a page or two is left out entirely. DMP folks have talked on their forums about this, and apparently they regularly consult with bookstore buyers about permissible content for their less-explicit June imprint; it appears that said buyers prefer an absence of visible genitalia or body fluids, and the art is frequently retouched to obscure such content. Fans hate this, of course, especially in books that are 18+ anyway. Fortunately, it seems that this sort of adjustment is becoming less common, perhaps under the influence of certain very strong-selling explicit titles (Junjo Romantica, DMP’s Viewfinder re-release).

Also, this is only part of more general trends of censorship in manga; Japanese publishers have rather different ideas of how much nudity, sexual innuendo, etc is appropriate for different age levels, not to mention stuff like smoking and “hand gestures”, and quite a lot of manga gets “tweaked” for the American edition. An article that mentions some examples (mildly NSFW):

http://io9.com/5383540/dragon-ball-spice-and-wolf-and-low+class-filth-in-manga-nsfw

If you mean taking books off the shelves completely, I don’t know of any case where books were actually pulled by the publisher (more that they go out of print, or the entire publisher folds), but there have been several public flaps where specific books have been removed from certain sales channels. In 2007, Walmart.com pulled some BL after complaints about the series Yaoi Hentai (a made-in-America, explicitly pornographic OEL comic):

http://www.icv2.com/articles/home/9968.html

And just recently, Amazon.com pulled a large number of Kindle titles including BL from several publishers as part of an apparent purge of Kindle porn, but also removed a few print BL books (no specific reasons were ever given, and some of the removed stuff was quite tame):

http://robot6.comicbookresources.com/2011/05/too-hot-for-kindle-amazon-pulls-yaoi-from-kindle-store/

In regards to Amazon bringing in new readers: online bookstores work great for people who already know of the material and are looking for it. For someone who hasn’t ever heard of BL, or is vaguely aware of it but hasn’t actually seen any, I don’t think it’s effective. Anecdotally, for people not already familiar with slash fanfiction and so forth, entrée into BL tends to come from one of three places: indoctrination by friends; exposure to a popular “almost-BL” series like Loveless or The Betrayal Knows My Name, followed by looking for “more like that”; or just tripping across the stuff at random. Amazon.com doesn’t really facilitate the latter, except via the Kindle books, and I don’t think the Kindle Store has the degree of market penetration Borders had.

____________________

Email interview with Lillian Diaz-Przybyl, a former senior editor at Tokyopop

Noah: I know Tokyopop had a close relationship with Borders initially when the manga boom started. Did that relationship continue over time? Did Tokyopop develop similarly close relationships with other stores, or did Borders always do better in carrying manga?

Did the problems at Borders (which I know has been struggling for years) contribute to Tokyopop’s struggles? Or were they mostly separate issues?

Have other companies taken up the slack left behind by Tokyopop’s disappearance? Or are there just less titles out there now and for the forseeable future?

Will places like B&N or Amazon or digital services fill the space left by Borders? Or will there just be less products available for manga fans?

With the end of Borders and Tokyopop, is this the end of the manga boom?

Lillian: 1. Credit where credit is due—a huge part of the influence that Borders had on the manga market was thanks to Kurt Hassler, who was the buyer for the section for quite some time. He was a great supporter of manga, and brought a lot of things into the section that might not have been there otherwise (boys love being the prime example, but there are others as well, including what we called original global manga, and a variety of merchandise). After he left to run Yen Press, there were still good connections with the buyers, but that was coincidentally the start of a long downward spiral in terms of how we worked with the chain. But we had great relationships with the other stores as well, even from the start. We did very solid business in the South, for instance, thanks to the Books a Million chain—and with a lot of the mature titles, too, which was the unexpected part. But B&N, for example, was generally a little more conservative in terms of what they would bring in. They were happy to take loads of Fruits Basket and the like, but took in fewer mature titles overall, and no mature-rated BL until last year when they tried Junjo Romantica as a test. That may be changing now, with the hole in the market (anecdotally, my local B&N has a nice, diverse line-up—but then, I live in Los Angeles), but I still see that initial risk-taking attitude on Borders’ part as a significant part of what helped grow the market back in the day, and that has never really been duplicated elsewhere.

2. Yup, Borders’ troubles most definitely affected us. Waldenbooks had always been a strong market of ours, so those stores closing down was a significant blow, and that was just the beginning. Over the last three years there were a variety of issues that we were dealing with, from how they were handling bill payment versus returns, to how aggressive they were with promoting new series, to how reliable their order numbers were. They still remained about 1/3 of our market up until the end, though, so the final impact of the bankruptcy troubles from the beginning of this year were significant (it directly led to me being laid off, for one). And every minute that your sales team is spending trying to work out problems with one distributor is a minute when they’re not thinking of new strategies to be competitive in an increasingly tight market. That’s certainly not to say that TP didn’t have its share of other problems (because it did), but that was kind of the straw that broke the camel’s back.

3. Speaking from experience, “rescuing” dropped titles is a tricky business, especially since manga is a very trend-driven market, so I wouldn’t expect to see many of TP’s old series out in print release from our former rivals, if that’s what you mean. (What the J-Manga consortium has up their sleeves in that regard is anyone’s guess, though.) There are a few that are probably worth the effort to obtain, but for the most part I think the remaining companies are going to stay the course, rather than try to usurp the corner we’d been clinging to. Or rather, I think they’re better off exploring new avenues and new business models, instead of trying to regain TP’s past glory.

But to put this in perspective, the big manga market adjustment really happened in 2008 and 2009, when we went from publishing 40-odd titles a month to 20, and then to 10-15. Borders or no Borders (and Borders was definitely a factor in that decision for us), and whether we’re talking supply or demand, the US market just doesn’t support two companies printing 40-plus volumes a month, with several smaller publishers adding another 20 or 30 to the pile. TP learned that lesson the hard way three years ago, and everyone else followed shortly thereafter in one way or another, and that’s not going to get un-learned any time soon. If TP’d gone under in 2008 there may have been more of a rush to fill the vacuum, but at this point, except on an individual title level, I don’t think our catalogue is going to be that sorely missed by the market overall (Our charming personalities and flamboyant marketing campaigns, maybe, but that’s another story!). VIZ’s shojo titles may get a little bump from the people who aren’t buying Maid-Sama and Gakuen Alice anymore, and Yen may see a little uptick from people with no more Trinity Blood or Deadman Wonderland to buy, it’s not the gaping void it might have been if we’d gone under sooner.

4. If you mean print sales through Amazon, that’s certainly not going to make up the difference (people are generally surprised to know what a small percentage of our revenue came from Amazon—but remember that the manga market is primarily teenagers, and even now most of them don’t have credit cards), and I think B&N is going to stay comfortably where they are for the time being. Digital opportunities are definitely there, though. And I think it’s a very legitimate question to ask whether people whose local store was a Borders will now go further afield to buy print manga (and in some cases, it may be significantly further afield), or if they’ll just turn to the internet to get their fix.

To combine this question with your final one, in my mind, the print manga boom hit a plateau with the rise of the aggregator scanlation sites, when a tremendous volume of content became easily available for free. Borders closing may have been the nail in the coffin for TP, but if a huge portion of your potential customer base is just as happy reading comics on their computer (which they are), that has to be addressed. I love print books, and I believe there will always be a market for them, but the serialized and addictive quality of manga means that this is a crowd with a thirst for getting new content as quickly and easily as possible, and for a variety of reasons the traditional publishing model makes it difficult to satisfy that demand. Providing a compelling alternative to the scan sites is a major challenge on every level from tech to marketing to licensing, but especially after San Diego Comicon, it’s obvious that publishers are painfully aware of this, and are actively trying to come up with that new model. If all goes well, there may be a new manga boom! I just don’t know if it’ll be in the chain bookstores anymore…

______________

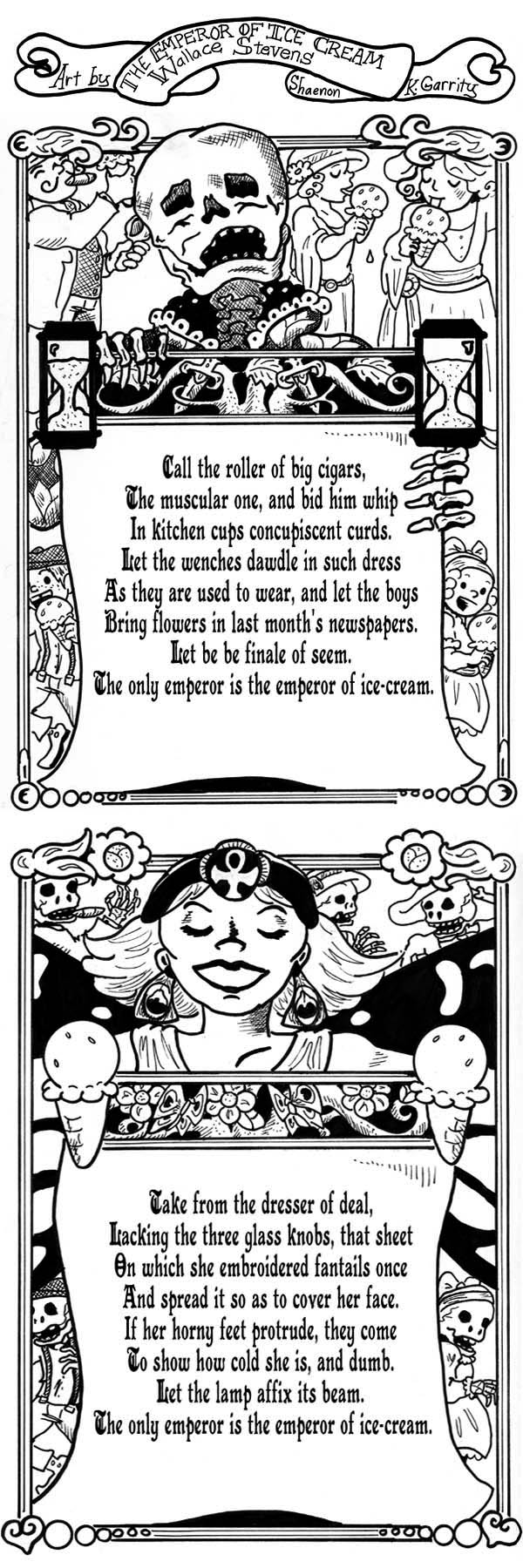

Email interview with Shaenon Garrity, cartoonist, critic, and a freelance editor for Viz

Noah: How important was Borders to manga outside of Tokyopop? Was it a major venue for other companies as well, or were they already more focused in B&N or Amazon or other locations?

Will the closing of Borders damage the sales of manga generally, and of Viz especially? Or do you think other venues (like B&N or Amazon or ebooks) will pick up the slack?

Does the twin demise of Borders and Tokyopop mean the manga boom is dead?

And maybe last…I’m curious if the end of Borders will have a particular effect on some niche manga. I saw some talk that it might be especially hard on BL readers…while on the other hand I assume there won’t be a ton of effect on higher end art manga. Is that your sense as well?

Shaenon: I don’t know all that much about the business end of manga, but I can answer these questions:

> Will the closing of Borders damage the sales of manga generally, and of Viz especially? Or do you think other venues (like B&N or Amazon or ebooks) will pick up the slack?

Publishers have been preparing for the Borders collapse for a while, so they’re already expanding into other venues. In the brick-and-mortar world, that includes Barnes & Noble, independent bookstores and small chains, and the comic-book direct market. There’s also a lot of interest in ebooks, especially Kindle and iPad editions, and in online comics in general, as evidenced by Viz’s big rollout of vizmanga.com at Comic-Con last week.

> Does the twin demise of Borders and Tokyopop mean the manga boom is dead?

I’d say the bubble has burst, but the big manga titles are still popular and selling well; it’s just that publishers’ overall output is settling to a less artificially inflated level. Instead of scrambling to flood the market with every available license, publishers are cutting back and being cautious in picking up new titles. I hesitate to point to Tokyopop’s situation as proof of the boom times ending, since Tokyopop’s business problems had little to do with sales of its manga, and ultimately the company folded because the guy running it just had interests elsewhere. I’m more concerned about the precarious status of smaller publishers, but with Viz still huge, DMP on the rise, and Japanese publishers getting directly involved in the American market, the industry keeps marching on. I get the impression that last year was the toughest year.

> And maybe last…I’m curious if the end of Borders will have a particular effect on some niche manga. I saw some talk that it might be especially hard on BL readers…while on the other hand I assume there won’t be a ton of effect on higher end art manga. Is that your sense as well?

For me, personally, the biggest problem with Borders closing is that Borders was very open to stocking yaoi/BL, and Barnes & Noble is not. I hope this situation changes, and that more bookstores get interested in BL. I’m saying this as a BL fan, of course, but also as someone who’s in the industry and believes that BL is going to be increasingly important as a steady seller to keep manga publishers profitable, just as romance novels keep print publishers profitable. Also, there are a bunch of awesome BL I want to see translated.