A couple of weeks back, Michael Arthur wrote an appreciation of Wandering Son by Shimura Takako, recently translated by Matt Thorn for Fantagraphics. Michael said:

That makes Wandering Son a most compelling fantasy, one in which the gentle-hearted are protected by their friends and youths hold the key to wisdom and self-knowledge in the form of a headband Would that every profoundly different kid were granted the same freedom and gentleness by society that pushes them in conflicting directions. Even this first volume, which focuses on the most flexible time in a kid’s life, is keenly aware of the unfairness of this system, which looms over a sissy or a tomboy like a distant god’s arbitrary cruelty. Wandering Son chooses for the most part to dwell on the possibility of choice, of self-knowledge and the love of a friend who knows your secret.

Having now read the book myself, I think that’s basically right: Wandering Son is a very gentle story. If anything, Michael overemphasizes the possibility of cruelty in the narrative. There is no bullying in this first volume, either physical or mental. No one expresses real outrage at the idea of queerness or cross-dressing. Nitori’s parents are a comforting, distant presence; his sister a typical sit-com older sister, spunky and sometimes cranky, but ultimately spporting. Nitori’s friends not only accept his dress-up impulses, but actively encourage them. Chiba seems positively titillated, and pushes girl’s clothes on him; Takatsuki is a soul mate, who wants to switch genders herself. The art, too, is insistently light; violence (a bicycle wreck, a brief fight) are pushed off panel; what remains is grade schoolers rendered in clear lines against often empty backgrounds, circular giant-eyed faces flecked with appealing blush marks staring limpidly as their noses disappear into their own radiant neoteny.

If I sound a little sardonic there at the end…well, what can I say. I am not categorically opposed to tweeness; Donovan is one of my favorite performers and I have a place in my heart for Cardcaptor Sakura. But even by those standards, Wandering Son’s preciousness can feel oppressive. Everyone is just so nice; so unwaveringly adorable. And that adorableness is tied ineluctably to the cross-dressing. Nitori’s fascination with girls’ clothes and Takako’s fascination with boys’ clothes serve as a metonymy for trans desires — a metonymy which is thoroughly externalized and fetishized. Their desires are certainly validated, but there’s a queasy sense in which they’re validated in the context of, and through, their cuteness. Queerness is swaddled in kawaii, lovingly packaged for a saccharine rush. It starts to feel ingratiating to the point of condescension.

Of course, the point of pop culture is, in a lot of ways, to be ingratiating. Superman caters to little boys’ gratuitous fantasies of power; Twilight caters to tween girls’ gratuitous fantasies of safety and romance. Wandering Son caters to the queer communities’ fantasies of acceptance. There’s nothing wrong with that. In fact, fulfilling the dreams of a marginalized group has a political charge that’s certainly significantly braver and more needed than reassuring the privileged of their own wonderfulness a la Clark and Bella. But though I can appreciate what Takako is doing politically, aesthetically I much prefer something like Moto Hagio’s “Hanshin: Half-God,” with its much less comforting insights into children, gender, friendship, and desire.

____________________

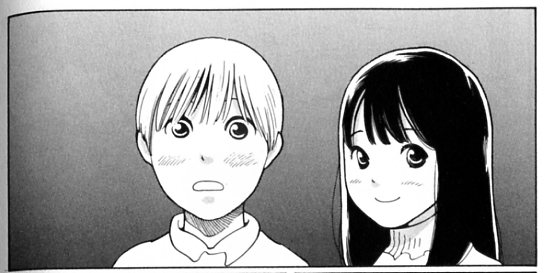

Not to end on a sour note…I did appreciate the skill with which Takako uses the comics medium to fulfill her remit. I was particularly struck by images like this:

So is that a boy or a girl?

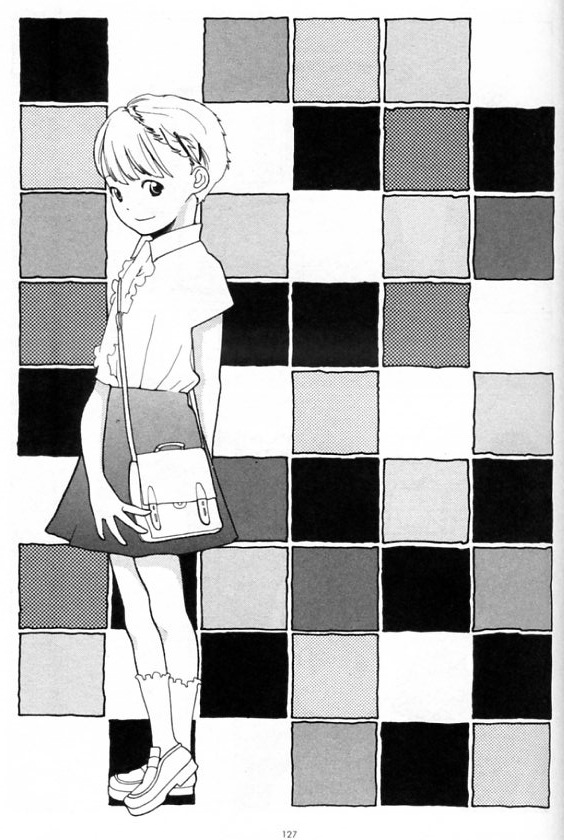

Presumably, the question is a tip off. And, indeed, it’s Nitori dressed in girl’s clothes. But the genius of it is that if you didn’t know the character, there would be no way to tell. Drawing a cartoon boy in girl’s clothes is no different than drawing a cartoon girl in girl’s clothes. The image is the same.

I’ve been reading a little bit of Lacan, and in his essay on the mirror stage he argues (to the extent I can figure out what he’s talking about) for the primacy of the image as self. That is, the child, for Lacan, sees itself in the mirror, and is overjoyed; it misidentifies the beautiful thing is sees as its being. This misidentification echoes, or anticipates, the later creation, through language and social connections, of the ego, which is also a misidentification of the self.

The point is that Takako seems to be channeling some of that magic, that joy, that Lacan attributes to the child looking in the mirror. Nitori is that image of a girl. If that’s what he looks like, that’s what she is. The imaginary can trump the social. Which is an empowering message, even if I wish it weren’t maybe quite so demure or noseless.