Dreams seem like the most private of things, and yet in some ways they’re the parts of us that are least us. With consciousness sidelined, everything and everyone else takes their place in your head. Freud and Jung may not have been exactly right that you can unwind a person by unwinding their dreams, but I think they were correct to claim that dreams aren’t so much a window into the soul as a creepy acknowledgment that the soul you’d thought you’d kept in a safe place is always already in somebody else’s pocket.

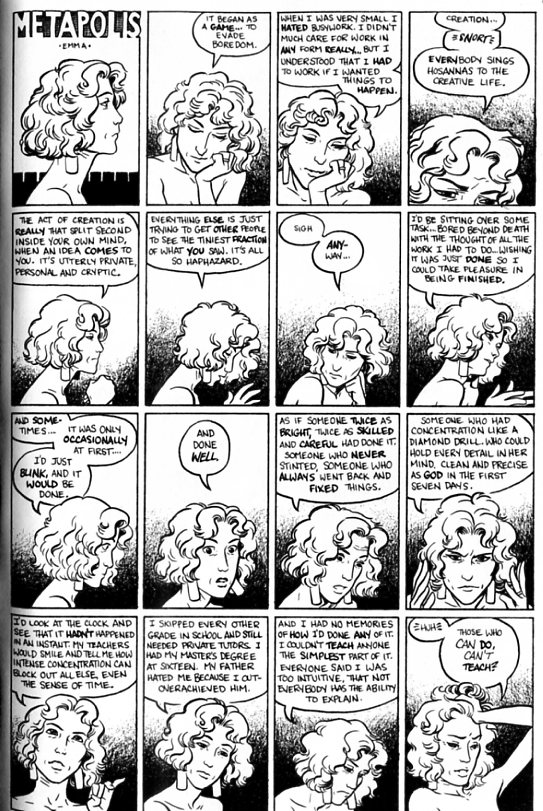

In “Sin-Eater”, Carla Speed McNeil’s first sci-fi Finder story, one of the main characters is a woman named Emma. Emma regularly has elaborate, disassociative dreams in which she imagines herself a fabulous princess in a distant realm. Sometimes when she’s gone, she lies as if asleep; sometimes she continues on with her life raising her kids and making her gardening eco-art without thinking or feeling or remembering how she did it.

Emma’s fantasy world is, obviously, a metaphor or analog for McNeil’s world which, like Emma’s, is elaborate and fantastical — a cyberpunk fantasy bricolage filled with talking animals and prophecies and even a venereal fey plague that gives people fox heads. Emma, then, is McNeil; a builder constructing a solipsistic interior castle, worlds within worlds, with emotions flickering across the page like carefully limned expressions across a mirror, the edifice an exercise in joyfully/painfully misrecognizing the self in its all its iterated containers.

But at the same time as Emma spirals inward, she spirals outward as well. The woman with the fantasy-world inside her is not exactly an original idea. I thought immediately of Neil Gaiman’s A Game of YOu, which could well have been an inspiration for McNeil (the timing’s about right, and Gaiman pops up in the copious notes at least once.)

Slightly further afield, I was reminded of Anna Freud’s 1922 essay Beating Fantasies and Daydreams in which she analyzes the fantasies of “a girl of about fifteen.” The girl is, of course, Anna Freud herself, and she traces her own rich fantasy life to a daydream she had as a five or six year old involving an adult beating a boy. Following in her own father’s footsteps, she interpreted these dreams as fantasies about father love; the father was beating someone else, which meant, according to Freud, that “Father loves only me.”

The daydreams were highly sexual, and in a guilty effort to suppress them and simultaneously enjoy them, Freud elaborated long, intricate narratives and worlds. Here’s her discussion of her main hero (she refers to herself in the third person.)

One of these main figures is the noble youth whom the daydreamer has endowed with all possible good and attractive characteristics; the other one is the knight of the castle who is depicted as sinister and violent. The opposition between the two is further intensified by the addition of several incidents from their past family histories-so that the whole setting is one of apparently irreconcilable antagonism between one who is strong and mighty and another who is weak and in the power of the former….

All this takes place in vividly animated and dramatically moving scenes. In each the daydreamer experiences the full excitement of the threatened youth’s anxiety and fortitude. At the moment when the wrath and rage of the torturer are transformed into pity and benevolence-that is to say, at the climax of each scene-the excitement resolves itself into a feeling of happiness.

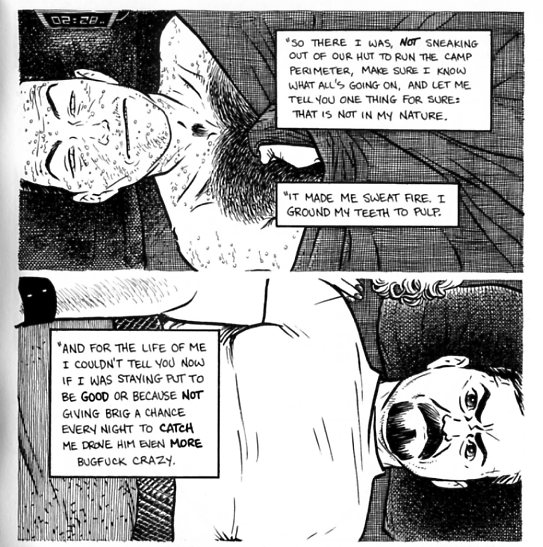

If you’ve read “Sin-Eater,” the connection between Anna Freud’s fantasies and McNeill’s fantasies should be apparent enough. Like Anna, McNeil’s story is obsessed with abuse — the main character, Jaeger, has a past which is basically one long series of fights, anchored by his decision to become a sin-eater, a sacrificial station that involves ritual beatings. As a sin-eater, Jaegar takes others’ wrath and rage and transforms it into pity and benevolence — a process aided by a mysterious healing ability which allows him to recover even from brain damage.

Moreover, “Sin-Eater,” like Anna Freud, has daddy issues up the wazoo. Emma’s former husband, Brig, psychologically abused her and her three children; Jaegar, who is Emma’s boyfriend, is a kind of substitute father figure — which is complicated by the fact that Brig served as a kind of substitute father figure for Jaegar himself. At one point, Jaegar actually builds a fake apartment for Brig to go to, fooling him into thinking his family is there rather than elsewhere. The displaced family obscures the fact that it’s not the wife and kids, but Brig and Jaegar who are constantly displaced, swapping one for another — as in this mirrored doubling.

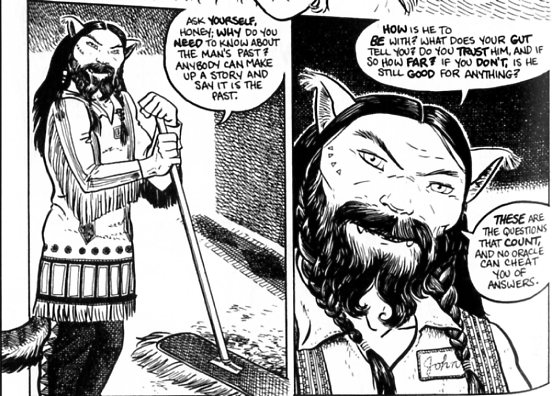

Or another example:

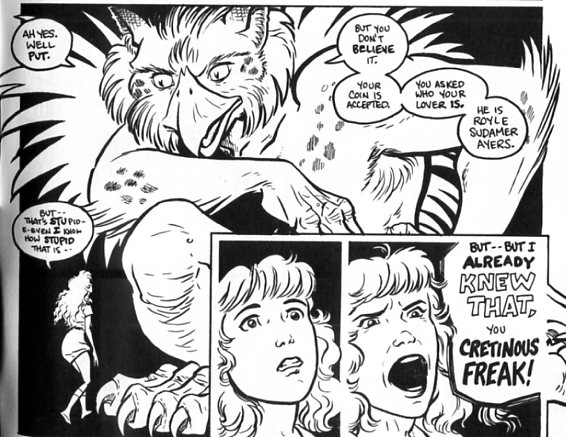

In the notes, McNeil says that this character is an early prototype of Jaegar. This early form is nonhuman, obviously — but it also has a beard not unlike Brig’s. And this dual Jaegar/Brig character is definitely an ambivalent father figure; it dispenses wisdom, but it is also connected to the oracle, which on the previous pages made Rachel (Emma’s oldest daughter) reveal her deepest fear. Rachel says her worst fear is “better the devil that you know” — an ambiguous statement that might be a little clearer if she’d said “better the daddy that you know.” Or, to put it another way, her greatest fear is the oracle, who towers over her as if she’s a small child and to which she reacts with a mixture of awe, fear, and petulance.

Again, this frightening oracle transforms into the proto-Jaegar, just as Jaegar takes Brig’s place in the family. The shuttling of father figures in and out puts a different twist on Anna Freud’s interpretation of her dreams. For her, the beating figure is the father, and those beaten are rivals for his affection. But if the father figure can shift from one place to another, why couldn’t he be the beaten as well as the beater? Couldn’t the point be vengeance upon the father by the (daughter identifying with) the father, a bid not for the father’s favor but for an economy which would grant power over the father to force him to identify with the (beaten) daughter? Father, then, becomes beaten and beater, and the happiness is from switching him from one to another, so that each punishes and then is punished for punishing, a cycle in which the powerful are humbled and the humbled empowered, so daughter is ever daddy and daddy is ever daughter.

Certainly in Sin-Eater the fathers take a massive and almost unending whupping. Brig is tricked, crippled, and finally rendered a howling, slobbering shell of himself; his son Lynn (who sometimes identifies as a girl, and sometimes as a boy), even injects him with battery acid. Jaegar, as we’ve mentioned, is constantly getting beaten up, falling from windows, mutilating himself, letting others mutilate him, and then healing and coming back. Ultimately he takes responsibility for the sins of Brig as well…spiritually changing the bad father to the good father, who apologizes and atones. (Plus there is the added bonus that Rachel can flirt with Jaegar unashamedly; he’s not her “real” father, after all.)

Which is to say, though the different clans and the background notes and the make it feel like a personal construction, “Sin-Eater” ends up as something very like idfic, pulling its power from the same well of chastened Daddy-lover fantasies as something like Twilight.

No wonder, then, that Jaegar is himself in many ways a drearily familiar archetype — the tortured tough-but-tender loner with heart-of, whose masculine ability to withstand pain functions as an excuse to subject him to hyperbolic and repetitive sensual violence, just as his mysterious outsider status turns him into a perpetually sexy invader of the quiet homes. Rachel accuses him at the end of the book of running out on the family because he fears that if he becomes less mysterious, they will reject him. But surely it’s McNeil herself who wants the outsider to be an outsider — she’s the one who made him in all his fascinating outsiderness after all. He’s a hyperbolic caricature of the bad boy who can’t commit; he gets physically ill when he’s cooped up too long, and then has to masochistically damage himself to regain equilibrium. Constantly disappointing and atoning, he’s forever attractively distant and adorably sorry for his distance; always that elusive first love, never the boring…well, daddy.

McNeill’s dreams, then, like Emma’s, are of genre — the most secret recesses of her heart are tropes. McNeill certainly knows that; she includes many wry allusions to other cultural touchstones (the Peanuts reference is a favorite especially.) Which would be fine…if I hadn’t run out of patience with the elusive, invulnerable Wolverine and all his sexily ambivalent loner brethren some time back. I don’t want to love him; I don’t want to enjoy his torment; I just want him to go away. But there he is, the angsty grain of sand at the center of the gloriously dreaming bivalve. Alas, I’m afraid that particular irritant’s been scraping my psyche too long already for me to really appreciate the pearl, however lovely its fashioning.