Michael DeForge destroys his sketches. He finishes his sketchbooks and then throws them away. This is a different approach to art than I am used to. For me, the sketchbook has always been a personal object. The closest approximation to an artist’s brain without telepathy. Personal letters to oneself. Sketchbooks are the work behind The Work. Many artists keep all of their sketchbooks, whether they look at them again or not. DeForge tosses his when he is finished. So I rethink what it is a sketchbook is for.

Michael DeForge publishes a lot of work. He has comic books from Koyama Press and Drawn & Quarterly. He self-publishes minicomics. He has comics in various anthologies. He posts things on his blog. He does commercial illustration. I would imagine that for him, the work itself in its final form is the personal journal of his progress. It could be that the sketchbook is merely practice. Raw, unsentimental practice.

If an artist uses sketchbooks for practice and not as some sort of defacto art project in and of itself, perhaps that artist no longer has use of the preliminary work. After all, we cartoonists think nothing of erasing our pencil lines after the ink is dry. What is the difference, now that I think of it? Why should the bound book of rough drawings be fetishized? When the final project is published, the rough work is… ?????

________________________

My conception of sketchbook use was largely based around the idea of something between a diary and a catalogue of ideas. One problem for me is the struggle between practicing artcraft in a sketchbook and allowing the sketchbook to become the artwork itself.

I had a class in art school called Sketchbook Creation. The course was inspired by Alan Gordon, the professor’s travels across the country in which he made his paintings on the go in a bound book. His idea for the course was to help the students open up their imaginations through particular exercises and controlled free-associations. In the end most of us sort of ended up making work that looked like his. Some of us continued for years after graduation, making finished art in books of heavy paper. Portable, but shackled to a relatively restrained format. Sketchbooks weren’t practice anymore. They were the art itself.

Imagine having a sketchbook for your sketchbook.

Imagine sitting in front of the tool which is designed to be an outlet for experimentation and being unable to experiment because it has been recontextualized as yet another Grand Canvas. Sketchbook Creation was my best class in art school but it also shackled me and ruined me in some ways. I hardly doodled anymore. Every drawing had to be good enough to show people. To be fair to Alan, the film “Crumb” had previously contributed heavily to this tendency for me.

Things got better when I started talking to people who use their sketch books only to practice for projects that they were working on. It took a while to overcome the pressure that I had internalized about making “showpieces” in my sketchbooks but I feel as though I’m turning a new corner now.

________________________

As I get older I have been growing more acclimated to the idea of impermanence. Not simply the idea that things change but more the idea that things are never fixed to begin with. Age gives perspective. We see a larger picture as we get older because events and phenomena take up a smaller percentage of our perspective as our years of existence increase. Six years means “since forever” when you are six years old. Six years means “as long as you’ve lived in this city” when you are thirty. Six years probably means very little when you are eighty-six. Your view cannot help but change as you take in more and more life experience. Things were never as “stable” as I thought they were when I was a child, I just lacked the experience to notice the movements.

In many ways an artist’s work has a life cycle as well. It’s “conceived,” no pun intended, it grows as the artist pours more work into it. The work matures and is sent into the world. At this point, we consider the tangible remnants of an art work’s youth. Do we save it in a drawer as humans do with their children’s baby clothes, perhaps in hopes of some future use? Or do we discard the husk as insects do?

I’m neither seeking nor am I suggesting an answer. Ultimately it’s a personality and lifestyle choice. As I stand amid the chaos of my bedroom, I would do well to cast away my preliminary drawings like a snake’s old skin. Being unsentimental about these things could probably spur me forward into being much more productive, as I tend to clutch things I’ve made, things I own. On the other hand, there are artists such as my old professor for whom “sketches” and cast off ideas are as treasured and valued as gallery paintings. Of course there isn’t a right or a wrong answer. The question itself is rhetorical.

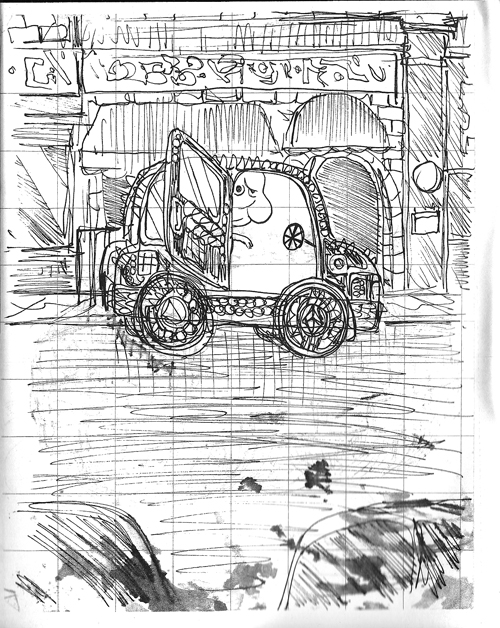

Drawing by Michael DeForge