This first appeared on Splice Today.

_______

According to Godwin’s Law, whoever compares their opponents to Hitler first in an online argument loses. Maybe it’s time to develop a similar rule of thumb for comparisons to chattel slavery. Stop Patriarchy an activist group which presents itself as fighting for reproductive rights in Texas has been especially busy recently in promulgating poorly thought through slavery comparisons, as in this tweet. “BREAK THE CHAINS! BREAK! BREAK! THE CHAINS! IF WOMEN DON’T HAVE RIGHTS WE ARE NOTHING BUT SLAVES.” Just to make sure you don’t think it’s a one-off mistake, their twitter bio helpfully declares, “End Pornography & Patriarchy: The Enslavement and Degradation of Women!”

According to Godwin’s Law, whoever compares their opponents to Hitler first in an online argument loses. Maybe it’s time to develop a similar rule of thumb for comparisons to chattel slavery. Stop Patriarchy an activist group which presents itself as fighting for reproductive rights in Texas has been especially busy recently in promulgating poorly thought through slavery comparisons, as in this tweet. “BREAK THE CHAINS! BREAK! BREAK! THE CHAINS! IF WOMEN DON’T HAVE RIGHTS WE ARE NOTHING BUT SLAVES.” Just to make sure you don’t think it’s a one-off mistake, their twitter bio helpfully declares, “End Pornography & Patriarchy: The Enslavement and Degradation of Women!”

Local Texas anti-abortion groups have responded by fervently telling Stop Patriarchy to cut it out and go away. The all caps declamations do make you wonder though; why on earth does Stop Patriarchy think this is a good idea? What exactly is the comparison supposed to accomplish? What is appealing in taking this other, different oppression and casting it in the language of slavery? Is it just a particularly clumsy way to say, “curtailing reproductive rights is really bad”? Or what?

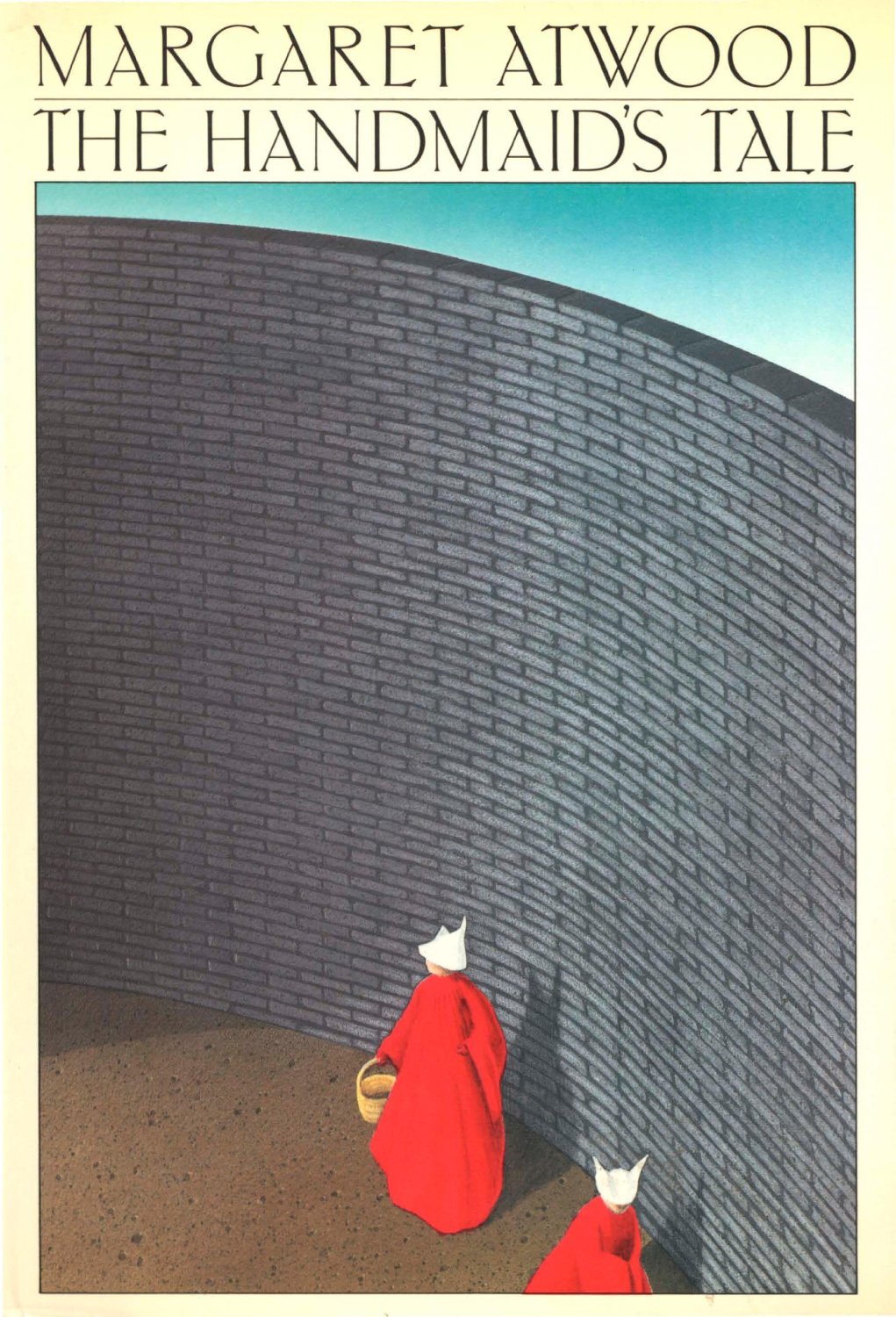

One way to answer that question is to consider one of the most famous feminist novels of the last thirty years: Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale. Atwood’s novel, published in 1985, is set in a dystopian near future in which right-wing family-values religious fanatics have taken control of the United States. The nameless protagonist and narrator was a librarian prior to the coup. The new rulers stripped her of her money, her profession, and her child and marriage, the last of which is considered invalid since her husband was previously divorced. She is forced by the new government of Gilead to become a Handmaid, assigned to various important men as a kind of official mistress, in hopes that she will bear them children — an imperative since chemical and radioactive pollution has sterilized much of the population.

The Handmaid’s Tale clearly owes a debt to other totalitarian dystopias, most notably 1984. But it also borrows liberally from the experiences of non-white women. In fact, the novel’s horror is basically a nightmare vision in which white, college-educated women like Atwood are forced to undergo the experiences of women of color.

This transposition is not especially subtle, nor meant to be. Handmaids wear red, full-body coverings and veils which reference the burqa. In case the parallel isn’t sufficiently obvious, Atwood has her narrator directly compare the Handmaids waiting to perform their procreative duties to “paintings of harems, fat women lolling on divans, turbans on their heads, or velvet caps, being fanned with peacock tails, a eunuch in the background standing guard.” The narrator has been teleported into an Orientalist fever dream, the irony only emphasized early in the novel by a group of modern, Japanese tourists, who stare at the debased Occidental women just as Westerners stereotypically stare at the debased women of the Orient. The stigma against Islam is leveraged along with, and blurs into, the stigma against prostitutes; the horror here is that middle-class, college-educated white women will be forced into the position of sex workers.

Slave experiences are appropriated with similar bluntness. The network that secretly ferrets Handmaid refugees over the border to Canada in the novel is called, with painful obliviousness, the Underground Femaleroad. We learn, in an aside, that the regime hates the song “Amazing Grace” — originally an anti-slavery song. It’s reference to “freedom” has been repurposed here to apply to Gilead’s gender inequities. The specific oppressions the Handmaids face also seem lifted from slave experience — they have their children taken from them; they are not allowed to read; they need passes to go out; if they violate any of innumerable rules, they are publicly hanged. The tension between white mistresses and black women on slave plantations is even reproduced; the narrator’s Commander wants to see her outside of the proscribed procreation ceremony. She of course can’t refuse — even when she finds out it provokes the commander’s wife to dangerous sexual jealousy. This is a familiar dynamic from any number of slave narratives (12 Years a Slave is a high-profile recent example) with the one difference that here, not just the oppressor, but the oppressed, is white.

Atwood is hardly the first science-fiction author to create a white future from elements of past non-white oppression. As I’ve written before , this kind of reversal is central to the genre; H.G. Wells, explicitly compares the invasion of the Martians in The War of the Worlds to European colonization of Tasmania. Wells explicitly presents this parallel as a moral lesson; he asks Europeans to imagine themselves in the position of the colonized, and to think about how that would feel. You could argue, perhaps, that Atwood is doing something similar — that she’s trying to get white people, and particularly white women, to imagine themselves in the position of non-white women, and to be more appreciative of and sympathetic to their struggles. You could see The Handmaid’s Tale as analogous to Orange Is The New Black, where a white women is a convenient point of entry to focus on and think about the lives of non-white women.

Orange Is the New Black actually includes Black and Latina women as characters, though.The Handmaid’s Tale emphatically does not. The book does say that the Gilead regime is very racist, but the one direct mention of black people in the book is an assertion of their erasure. The narrator sees a news report which declares that “Resettlement of the Children of Ham is continuing on schedule.” Here Atwood and Gilead seem almost to be in cahoots, resettling black people somewhere else, so that we can focus, untroubled by competing trauma, on the oppression of white people.

Atwood and Gilead are in cahoots in some sense; Atwood created Gilead. You can hear an echo of the writer’s thoughts, perhaps, in Moira, the narrator’s radical lesbian friend, who is not shocked by the Gilead takeover. Instead, the narrator says, “In some strange way [Moira] was gleeful, as if this was what she’d been expecting for some time and now she’d been proven right.” The Handmaid’s Tale presents a world in which white middle-class women are violently oppressed by Christian religious fanatics. As such, it is not just a dystopia, but a kind of utopia, the function of which, as Moira says, is to prove a certain kind of feminist vision right.

That vision is one in which women — and effectively white women — contain all oppressions within themselves. The Handmaid’s Tale is a dream of vaunting, guiltless suffering. Maybe that’s why Stop Patriarchy finds the slavery metaphor so appealing as well. Using slavery as a comparison is not just an intensifier, but a way to erase a complicated, uncomfortable history in which the oppressed can also sometimes be oppressors.