“Dear Reporter,

I am 29 years old.

Some of my friends tell me Captain America doesn’t matter, because he’s just a comic book character. Please tell me the truth; is there a Captain America?

Virginia”

Yes, Virginia, there is a Captain America. If you look in history books, you may not see him, but what does that prove? The most important figures of history are not written and recorded with facts and figures to support them. Captain America exists as surely as this country exists, and this country could not exist as such without his righteousness and courage. He exists as certainly as compassion and respect for fellow men, and we know that these qualities abound and give our land its highest grace and virtue.

Not believe in Captain America! We have always believed in Captain America; only think how different the world would be if we did not believe in him. How could we have won the second World War without Captain America’s fortitude and bravery? He would lay down his life in order to uphold liberty and justice. He believed in these things even though he could not see them—how can we then not believe in him? Men have died because they believed in truth and the pursuit of happiness—because they believed in Captain America.

Do you think that men would go to war for purple mountains, or fruited plains, or even gasoline? You may think these things are real, but if you took these things away, you would still have bigotry and exploitation, avarice and hatred, just as you would still have love and honor. Are they real? Ah, Virginia, in this world there is nothing else real and abiding.

Of course Captain America exists. Without Captain America, we would never have had the courage to hold fast to our convictions! We also would never have had the hubris.

Without Captain America to sanctify our actions, we never would have believed that we know best. Without Captain America’s super-strength to support us, we never would have believed that we would win. Because we believe in freedom, we have sought to impose our version of freedom, even if it makes people less free. We have sought to impose our versions of justice and fair play, when it is not just and not fair.

Virginia, your little friends are wrong. Your little friends have seen little men do horrible, atrocious things, and therefore the believe that Captain America must not exist because he did not stop him. Your little friends have seen our country act not out of justice, but out of fear. They have seen us act not out of compassion, but out of pride. They have seen us abuse power and trample the already downtrodden, but what your little friends don’t know is that we have done so because we believe in Captain America.

In the sixties, plenty of people didn’t believe in Captain America. Some thought others took the name; other people thought he was sleeping in ice; others thought he was dead, and some believed that he never existed, just like your little friends. There was a reason Captain America slept: we didn’t believe in him anymore. I don’t think anyone stopped believing in what he stood for, but we began to doubt the fact of this super hero, because we realized he was just a man.

We realized he was just a man, because he has a face. Even if you have never seen this face in person, you know what it looks like: fair, blue-eyed, blond. Captain America is tall and white, heterosexual and Christain, male and middle class, and we know that he exists because that is not what America looks like. That is what a man looks like, just one man.

We have not been honest with other nations; our leaders have not been honest with us, and we have not been honest with ourselves, because for so long, we didn’t face the fact that Captain America was real—and just a man. Because Captain America exists, he can lie and cheat and kill just like the rest of us—and he did. Captain America is a killer; at times, Captain America has been a war-monger. Captain America told us his enemies were evil, and we believed in him just as we believed in evil. Captain America, among other things, can lie.

You may have written me today because recently Captain America seems more alive than ever. Maybe your little friends are wondering, “Is it the same Captain America?” This is where your little friends might be onto something.

Let me tell you about a friend of mine, Virginia. His name is Steve Rogers. Steve woke up one day, and found out the world had gone on without him, and it had changed. Steve believes in all those things that Captain America did: freedom, justice, compassion, honesty, but he doesn’t know how to act on them anymore. The world is not as simple as it once was. It is no longer acceptable to help one person by punching another in the face, and the worst part is—maybe it never was.

What does Steve Rogers do in such a world? How does he help people now? How does Steve Rogers go to a third world country and say, “I want to help you,” without being Captain America, the man who caused so many problems in the first place? How does Steve Rogers extend a hand of peace, without those former foes remembering that that hand once punched them in the face? I know that Steve Rogers exists because he has asked me these questions. Maybe you have too, Virginia.

Captain America exists. Maybe he has changed, or maybe we look at him differently now. Perhaps this is why your little friends think he isn’t real. Maybe Steve Rogers thinks Captain America isn’t real either. Maybe for all of us, just like for him, the important part isn’t the dreams we have, but what the world looks like when we wake up.

____________

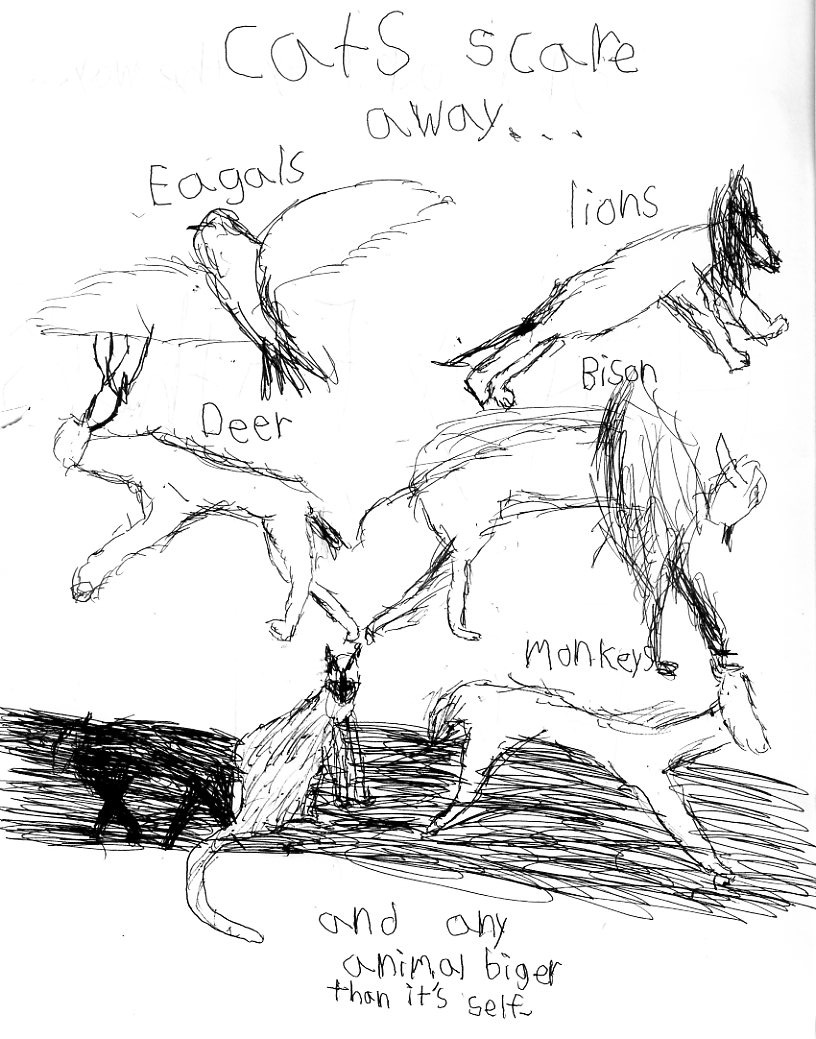

The illustration for this post is by editor Noah Berlatsky’s 9-year-old son.