I don’t know his name, just his origin. He starts out as a standard lab-coated scientist, arms stretched into a pair of wall-mounted containment gloves as he peers through an observation window at a glowing meteorite in his rubbery fingers. The protective wall is thick, which is why he survives the explosion. When he wakes in a hospital bed, he’s blind and armless. He’ll later grow phantom limbs—literally, their outlines are hazy with the meteorite’s mysterious energy—plus multi-dimensional vision, but first he has to face the horror of his ruined body.

The images look like comic book panels, drawn in Marvel house style c. 1980, but they exist only in my head. I’m remembering one of my adolescent daydreams. I never named my would-be superhero, so I’m retroactively dubbing him: Post-Traumatic Growth Man.

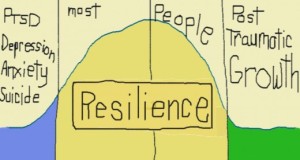

Jim Rendon introduced me to the term. Psychologists Richard Tedeschi and Lawrence Calhoun coined it in 1995, and Rendon wrote about it in his New York Times Magazine “Post-Traumatic Stress’s Surprisingly Positive Flip Side.” Rendon is expanding the article into a book for Simon and Schuster now, and he emailed my university address looking for a professor willing to talk superheroes. He said he was hoping to learn more from me, but he’d already done his homework:

“It is the archetypal story of the hero who is forged through adversity by completing a life-threatening quest, suffering the loss of loved ones, surviving the destruction of home. Through survival of trauma, the hero becomes a great and selfless leader. And in popular culture narratives, nearly every comic book hero suffers some loss that spurs him or her to greatness–Batman, Spiderman, Superman, etc.”

I suggested he read Austin Grossman’s 2007 superhero novel Soon I Will Be Invincible. Grossman told an interviewer that trauma is “the motivating, defining attribute of the superhero. I guess it’s kind of the hopeful element of superhero comics; the idea of the trauma that shapes you is not just pain; it’s also the thing that makes you special . . . .” Video game designer Jane McGonigal explored that same “hopeful element” when creating “SuperBetter” in which her superheroic avatar “Jane the Concussion Slayer” helped her overcome a real-life injury. But, Rendon asked me, where did this defining superhero attribute come from?

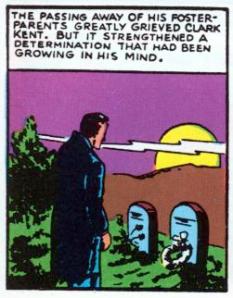

Well, Nietzsche, the man who gave us the ubermensch, said it first: “what does not kill me makes me stronger.” Jerry Siegel borrowed more than just the name. Look at Superman No. 1 and there’s Clark staring at a pair of gravestones: “The passing away of his foster-parents greatly grieved Clark Kent. But it strengthened a determination that had been growing in his mind.” Bruce Wayne’s superheroic response to his parents’ murders is even more overt: “And I swear by the spirits of my parents to avenge their deaths by spending the rest of my life warring on all criminals.”

But both origins were add-ons. Batman patrolled Detective Comics for six issues before an editor demanded Bob Kane provide an explanation. Superman No. 1 was a reprint of Action Comics adventures with an expanded origin that retconned Clark’s foster parents. In the first one-page origin, a passing motorist drops the alien baby at an orphanage. All those traumatically dead parents were afterthoughts.

Before the late 30s, superheroes didn’t know much about Post-Traumatic Growth. Doc Savage, the Shadow, Zorro, the Gray Seal, the Scarlet Pimpernel, all their do-goodery was equal parts altruism and thrill-seeking. Trauma didn’t fully hit the pulps till 1939, when the Black Bat got a face full of acid, and the Avenger’s family perished in a plane crash. Batman and Superman lost their ad hoc parents the same year, and soon almost every Golden Age hero—Green Arrow, the Flash, Plastic Man—had to have his own special tale of superhuman recovery.

U.S. Army recruits wouldn’t ship out for three years, but war was raging in Europe, and the comics are a surprisingly perceptive flip side to front page headlines. There are also some PTG tales earlier in the decade (the Domino Lady’s dad was murdered by gangsters), so Rendon wondered aloud on the phone whether the trope might be a national recovery tale: the U.S. rising heroically from its Depression. I like both those readings, but I don’t think superheroes really start growing, post-traumatically or otherwise, till the 60s. Stan Lee knew how to make a hero suffer.

Most unitard-wearers slap a defining symbol on their chest, a bit of iconic lip service to that supposedly life-transforming trauma, but Jack Kirby didn’t even draw a costume for the Thing. His body is his on-going disaster, one that extends well beyond the frames of this origin story. Peter Parker, like most Marvelites, should have died of radiation poisoning, but it’s the mental anguish of allowing his uncle to be murdered that spurs him to atonement. The crippled Donald Blake is just wobbling through his life until he finds a cane that transforms him into a god of thunder. After Tony Stark trips a jungle booby-trap (“Impossible to operate! Cannot live longer than a week!), he manufactures “a mighty electronic body, to keep [his] heart beating after the shrapnel reaches it!” For Doctor Strange’s fourth issue, Lee and Steve Ditko retconned a career-ending car accident that turned the wealthy neurosurgeon into a penniless vagabond—and then the Sorcerer Supreme.

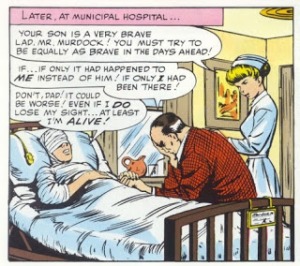

By 1964, Lee had exhausted his creative reserves, introducing his last but most post-traumatic superhero. After saving a blind man in a crosswalk, young Matt Murdock lies in a hospital bed, his head heavily bandaged after being struck by a radioactive cylinder that fell from the speeding truck.

NURSE: “Your son is a very brave lad, Mr. Murdock! You must try to be as equally brave in the days ahead!

DAD: “If . . . if only it had happened to ME instead of him!”

MATT: “Don’t, Dad! It could be worse! Even if I DO lose my sight . . . at least I’m ALIVE!”

That surprisingly positive attitude pays off two panels later. “I don’t get it!” says the now super-athletic Matt. “I seem able to do everything lots betters than before . . . even without my sight!” Throw in “razor sharp” senses and “built-in radar” and Daredevil is the PTG poster boy—but only because he remains blind. He’s why Grossman sees “the larger theme of superhero life as trauma and recovery from trauma; the way superpowers arise in trauma to the body that one never quite gets over. The trauma impresses itself onto the body but also leads to a hyperfunctioning of the body.”

That larger theme impressed itself on me too. My nameless but mutilated scientist and his eventually phantom-limbed persona were the unexamined DNA of Bronze Age comics. I absorbed the trope like radiation, and it filtered back out through my adolescent daydreams. And now Jim Rendon is studying it under his journalistic microscope. His book, Upside: Transforming Trauma into Growth, is due out in 2015–just in time for Daredevil’s premiere on Netflix. I’m looking forward to both.