A Review of The Times of Botchan (Part 2)

[Part 1 of this review can be found here]

(3) The Times of Botchan Vol. 1 & 2

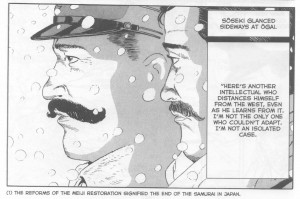

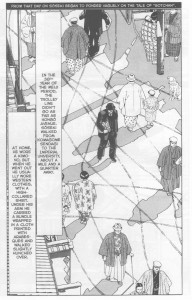

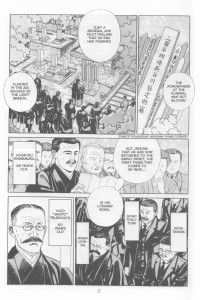

The closing pages of the fourth volume of The Times of Botchan are the high point of the first half of the manga series. It is here that the authors begin to present conversations that defy easy explanation and sequences that engender poignant contemplation. The first two volumes by comparison are unfocused and tentative, veering haphazardly from comical to more deeply intellectual episodes — as if the authors were uncertain of their audience’s ability to stick to a tale devoid of levity. Some might say that these transgressions are a function of the manga’s attempt to portray the birth of Soseki’s Botchan (which is a comic novel) but they also seem to be grappling with the immensity of the task ahead of them, as well as the ambiguous long-term future and direction of the project. There are some residual traces of this inconsistency in Volumes 3 and 4 of the series but all marks are virtually extinguished in the more focused, patient and sure-footed later volumes.

That this series is aimed at a select Japanese audience is evident very early on. While a casual Western reader might be expected to know of or even read some Soseki, it is doubtful if many would have knowledge of the poet, Ishikawa Takuboku. It is equally doubtful that this kind of knowledge would be available to the typical young Japanese manga reader. Yet Takuboku is mentioned five pages into the first volume of the book with nary an explanation and merely as a reference for Soseki’s comfortable salary.

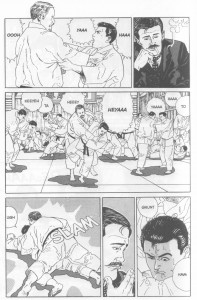

Sekikawa’s professed intention in the first two volumes of the manga — to fashion a story about the writing of Soseki’s Botchan — is less problematic since this novel is a much more popular work, particularly in Japan. At various points in their tale, the authors insert vignettes of Meiji life to suggest sources for Soseki’s ideas in Botchan. There are references to jujitsu just as there are in the novel where a character boasts about his abilities in that martial art.

The barroom brawl in the manga is perhaps meant as a precursor to the fracas between normal- and middle-school students toward the close of the novel. These sections will mean little or nothing to a person who has never read the novel. No such knowledge is required to appreciate the narratives of Volumes 3 and 4 of the series, which concern Ogai and Futabatei.

An uninformed reader perusing the manga in isolation could be forgiven for thinking that Botchan was a novel specifically about the modernization of Japan and the clash between Eastern and Western mores during the turbulent years of the Meiji era. In fact, it is, superficially at least, a somewhat gentle if satirical story of provincial life and its idiosyncrasies. Narrated by the eponymous hero, Botchan begins life as a self-proclaimed “great loser” who has done many “naughty things.” He is neglected both by his father and elder brother and is cared for, from the period of his mother’s death, by a kindly servant called, Kiyo.

As a young adult, he earns a college degree and accepts a teaching job far away from his native Tokyo in a provincial school. In a series of amusing encounters with his students, fellow teachers, hotel staff and landlord, he finds them almost without exception (at least initially) repulsive, giving them nicknames like Badger, Green Squash, Porcupine and Red-shirt (the “villain” of the story). Far from simple yokels, many turn out to be tasteless, backbiting, sexually unrestrained barbarians, even in comparison to his own brash and impulsive self.

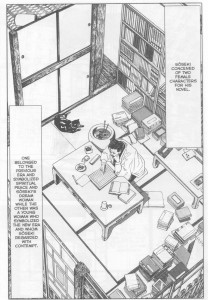

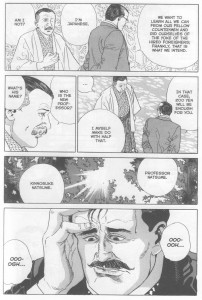

At the start of Chapter 11 of the manga, the authors provide us with a letter from Soseki to his editor, which reads, “Many things in the way the young men around me act have inspired me so the subject keeps on growing.” The young men we see around Soseki at the start of the manga are substitutes for the kind of men Soseki might have met during the writing of Botchan. Translator Umeji Sasaki attempts to point us in the right direction in his foreword to the novel:

“Old Japan with her polite, yet often deceptive, ways is passing to return no more, and New Japan with her honest, simple, frank democratic ways must come to speak and act in world terms. Botchan … is in many respects a young man embodying the new ideals of New Japan.”

Writing in 1922, Umeji does not question the desirability of the new ideals, nor is it entirely clear from our present-day perspective if the Old Japan he specifies has in fact passed away.

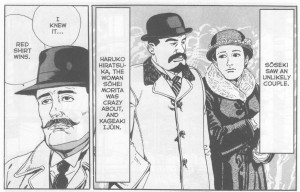

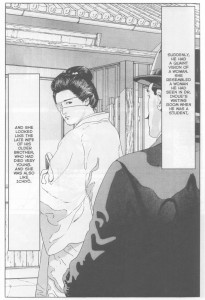

In the novel, the repulsive aspects of the New Japan are embodied in the character of Madonna, who was at one point engaged to Green Squash. As a consequence of some financial reversals suffered by her fiance, she has since drifted towards the villain of the piece, Red-shirt. This scenario is played out in the manga with real life individuals taking the place of literary ones. When Soseki sees the feminist writer and activist, Raicho Hiratsuka (a historical person) abandon one of his young friends for another of greater prestige, he can only say, “I knew it, Red-shirt wins”.

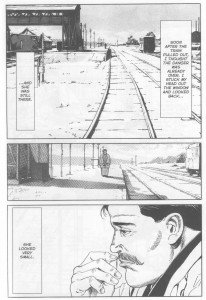

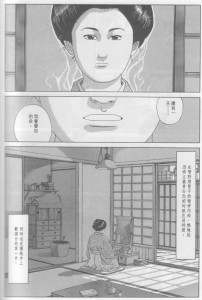

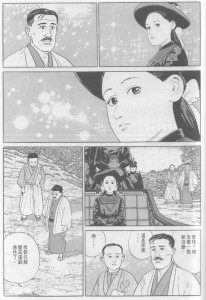

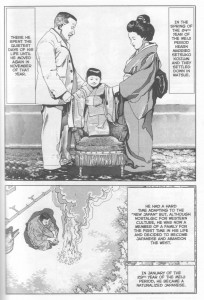

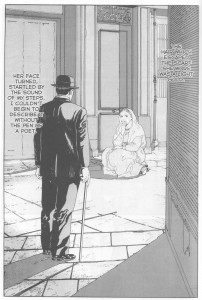

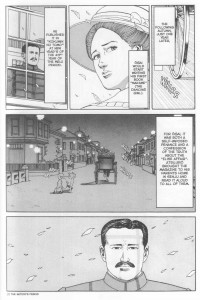

The authors close the first volume of The Times of Botchan with the image of Kiyo standing at the train station as she sees Botchan off to his new job. As Sekikawa explains, she “belonged to the previous era and symbolized spiritual peace and Soseki’s dream woman.” Soseki’s feelings as to this personification of a better time is apparent when Sekikawa reproduces the final sentences of the first chapter of Botchan in the manga:

“The locomotive began to move with its usual puff, puff. Thinking it quite safe now, I looked out of the window and turned to the spot where she had been standing. There she still stood, looking after me with a longing eye. She appeared so very small.”

Soseki’s vision of Kiyo toward the close of the second volume is that of a motherly woman with a patch over her right eye — a metaphor that doesn’t require much explanation.

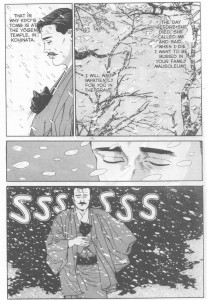

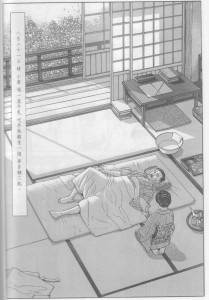

At the end of the novel, Botchan and Green Squash catch Red-shirt and his lackey Noda red-handed following a sexual escapade with some geisha. They beat them up but finally return to Tokyo where Botchan sets up house with his old servant (and surrogate mother), Kiyo. She dies soon after and asks to be buried in Botchan’s family graveyard. The second volume of the manga closes with Soseki gazing into his garden as Sekikawa’s narration melds subtly into commentary:

“Botchan had a place he could go home to. The house where Kiyo lived, that is, a place where an old fashioned spirit reigned.”

It should be stressed, however, that the authors never suggest that the values of Kiyo are inherently superior to those of Madonna — the Soseki of the manga is always sympathetic but he is not always right.

***

In his capsule review of the first two volumes, Chris Mautner suggests, quite rightly, that The Times of Botchan is “a book where your enjoyment is in direct proportion to your familiarity with the subject matter.” He offers this comment without criticism, but I would suggest that this is not only a failing but one that originates from inexperienced writing rather than any large deficit in the reader. In short, the first two volumes lack a certain universality born of a cluttered narrative and an everything-but-the-kitchen-sink approach — in particular the endless parade of peripheral historical personages who distract rather than enrich or engage. It is clear that many of the early sections of the book read too much like a textbook.

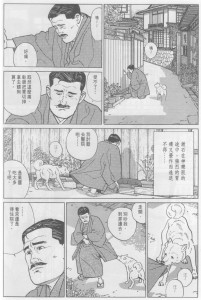

As it is, The Times of Botchan contains a procession of coincidences where the lives of historical characters somehow intersect in the same way that Kenneth Toomey seems to know every important personage of his time in Burgess’ Earthly Powers. For example, in the first volume, Soseki bumps into both Hideki Tojo and the man who would one day assassinate Hirobumi Ito (the first Prime Minister of Japan), Jung-Geun An. In the third volume, Futabatei encounters not only Elise Weigert, but also the feminist writer, Ichiyo Higuchi, (who currently appears on the 5000-yen note) all in the course of a single day. The latter meeting results in Futabatei’s adoption of Higuchi’s dog, which continues to pop up in the course of the entire series — sometimes as a passive observer and, at other times, simply hounding Soseki.

This is, of course, a perennial problem facing adaptors who try to shape and distill a basic structure from the denser whole of a novel or age. A similar dilemma faced the screenwriters for Luchino Visconti’s The Leopard when they attempted to explain the significance and flow of events during the Risorgimento to a modern Italian audience. A comparable situation can be found in Hiroshi Teshigahara’s Rikyu, a viewing of which can only be enhanced by a working knowledge of Warring States period Japan, though this information is never a prerequisite for one’s enjoyment of the film.

In the same vein, while certain readers may find the “simplicity” of Soseki’s writing style (as cultivated by his knowledge of classical Chinese literature and poetry) somewhat distancing, any inability to appreciate his works cannot be adequately blamed on cultural ignorance so much as a failure to perceive the complex undercurrents and structural intricacies which he is so skillful at hiding. One can read Botchan without once suspecting many of its underlying themes — the characters never become mere symbols. As Damien Flanagan in his introduction to Soseki’s The Gate writes:

“What is remarkable about the novel — indeed about all Soseki’s later novels — is that, although the structure of the novel is ultimately profoundly ironic, the portrayal of the characters is so sympathetic and realistic that this overarching scheme to complex ideas becomes almost invisible.”

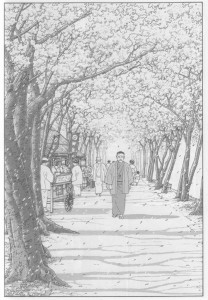

The first two volumes of The Times of Botchan would have been much finer and more coherent works had they been pared down to the essential aspects of the genesis of Soseki’s novel. Thankfully, readers will find that these problems recede quite swiftly with later volumes in the series, which bring on a fine maturing in both art and writing. The third and fourth volumes of the manga rarely betray the fine network of references and metaphors that lie over the series like a tapestry.

(4) The Times of Botchan Vol. 5-10

The forthcoming volumes of The Times of Botchan are biographies of other famous men and women who have responded to the changes of the Meiji era.

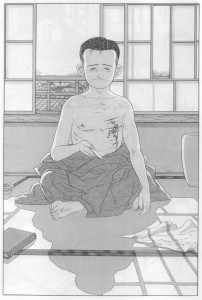

The fifth and sixth volumes tell the story Takuboku Ishikawa (1886-1912), a master of tanka, from his earliest days to his life as a newspaper editor. This section closes with some of the more startling episodes from his Romaji Diary (kept from April 7 to June 16 1909), which was never published during his lifetime. The most disquieting of these is the moment where he describes a misogynistic dalliance with an 18-year-old prostitute, in which he puts his fingers into the woman’s vagina and “roughly [churns] around inside” only to find that the sleeping woman only responds with pleasure when he begins to fist her. A month or so later he is cutting himself on the chest with a razor as a pretext for staying away from work. The manga describes the struggles and sheer dreariness of a poverty-stricken literary existence. His life, as vividly described in Romaji Diary, is often so filled with depression, bitterness and pain that it engenders a certain sympathy from the reader. The sixth volume ends with the same scene that closes Romaji Diary: the arrival of Takuboku’s mother and his wife, Setsuko, in Tokyo. (They had been living under the care of his friend in Hakodate up to that time because of his inability to support them.) This is not the happy circumstance one might expect. As Sandford Goldstein and Seishi Shinoda write in their introduction to their translation, “that key moment in Takuboku’s life was to prove a kind of breaking point. Several tanka in Sad Toys … the collection of poems written in the last year and a half of his life, record the conflict between Setsuko and Takuboku’s mother.”

The seventh and eighth volumes of the manga are the most overtly political of the entire series. They recount the lives of Shusui Kotoku (1871-1911) and Suga Kanno (1881-1911), whose response to the changing times was anarchy and rebellion. Together with nine others, both were executed after a trial for their parts in the Kotoku Incident (or High Treason Incident) which Goldstein and Shinoda call “the most revealing example of despotism during the Meiji era.” The detail with which their lives are brought to the attention of the reader bears comparison with the works of Jack Jackson and Chester Brown’s Louis Riel. Perhaps symbolically, Soseki begins to develop a more severe gastric problem in the closing pages of these two volumes. By the end of Vol. 10, Takuboku is writing about the death sentence of the anarchists involved in the Kotoku incident and experiencing the first signs of the peritoneal tuberculosis that will kill him in 1912.

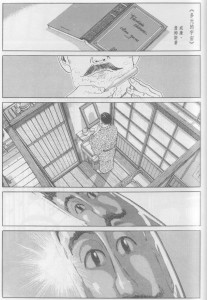

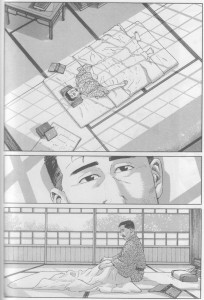

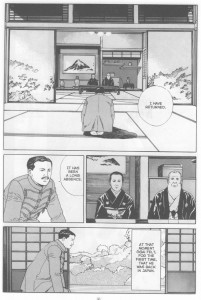

Both volumes nine and ten take in the closing years of Soseki’s life beginning with his sojourn at Shuzenji hot springs in 1910 to his coma and near-death experience following a massive hematemesis.

He is nursed by his estranged wife, Kyoko, who remains faceless throughout the narration as if in silent commentary on the hostility she has received from some students of Soseki. Soseki gives a kinder and much more complex portrayal of his wife in Grass on the Wayside. These volumes also record his vehement refusal of an honorary doctorate from the Japanese government on ethical grounds.

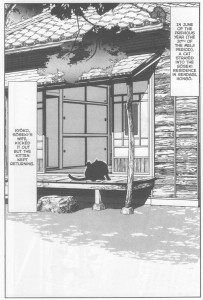

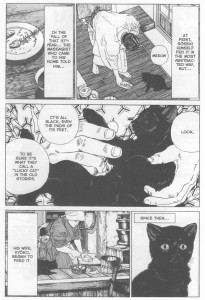

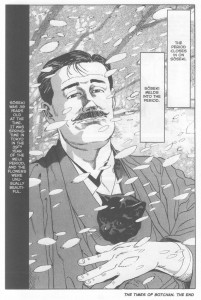

Making periodic appearances throughout the entire series, including its conclusion (if only spiritually) is a black cat. At the most basic level, this cat is the physical manifestation of Soseki’s inspiration for his first novel, I Am a Cat. Early in the novel, a massagist visits Soseki’s home and identifies it as a “lucky cat.”

More than this and as explained in the introduction to the Tuttle edition of I Am a Cat, Soseki was himself a kind of “stray kitten.” It has been suggested that both financial considerations and the advanced age of his parents at the time of his birth made him a source of embarrassment. As a result, he was placed in the care of a foster family till the age of 9 before rejoining his parents again upon the divorce of his adoptive parents. The cat thus represents both Soseki’s inner voice (at times playful, at other times serious and combative) as well as the vanishing times.

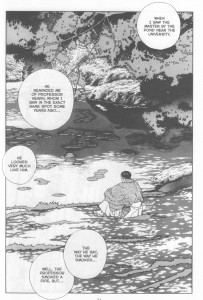

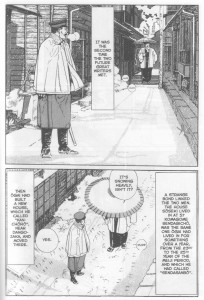

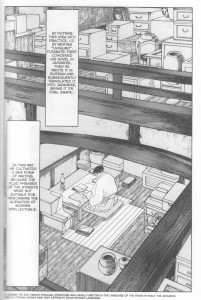

Of particular note in Vol. 10 is the 100-page discourse in the realm of dreams which begins in the chapter titled, “What are you doing here, Teacher?”

[Read from right to left]

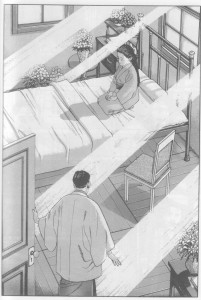

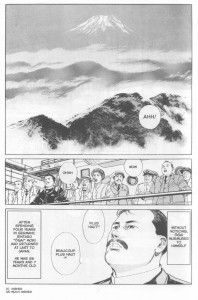

The initial moments of this dream are presented as a plausible reality, with Soseki attending to his morning toilet and meeting up with Takuboku. They discuss his present financial circumstances — a pet topic of both writers — and the progress he has made in his poetry. In the hotel restaurant, he encounters an older Ogai as he meets up with Elise many years after the events that inspired “Maihime”. Then, while employing various means of transportation, he meets his old teachers, political figures and the women who have enriched his days and writings in a grand summation of his life, his art, the times he has lived in and the manga series.

Readers familiar with Soseki’s novel Sanshiro (1908) will recognize this device; specifically a dream narrated by Professor Hirota toward the close of the novel where he encounters “a pretty young thing maybe 12 or 13.”. What follows in the manga is a partial transcription of this dream sequence with Soseki taking the place of Hirota. From the novel:

“Then I asked her, ‘Why haven’t you changed?’ and she said, ‘Because the year I had this face, the month I wore these clothes, and the day I had my hair like this is my favorite time of all.’ ‘What time is that?’ I asked her. ‘The day we met twenty years ago,’ she said. I wondered to myself, ‘Then why have I changed like this?’ and she told me, ‘Because you wanted to go on changing, moving toward something more beautiful.’ Then I said to her, ‘You are a painting,’ and she said, ‘You are a poem.'”

That day twenty years ago was the date of the funeral procession of Minister of Education, Arinori Mori (in 1889), where Hirota first caught a glimpse of the girl in her carriage. In his translation of Sanshiro, Jay Rubin indicates that “Soseki’s use of a public incident like the assassination…would seem to indicate that as he undertook to write the novel, he was thinking about a time in his life when he himself experienced a major disillusionment”. The girl in the manga differs from the girl in Sanshiro by the lack of a mole on her face, and the insertion of this sequence may hint at the authors’ intention to highlight Jun Eto’s thesis that Soseki had an affair with his sister-in-law, Tose, sometime around 1890.

It is also clear that they mean to suggest that Soseki the writer will “go on changing” as his works are interpreted and reinterpreted over the years, remaining as eternal as the cat, once thought dead, who appears alive again at the series’ close. The Times of Botchan is full of instances like these and more: there are incidental points hiding references and meaning; sociopolitical and literary analysis; vivid imaginings of long lost lives; and moments of ethereal beauty and mystery. There can be little doubt that it is one of the finest historical manga available to the comics reader today.

END