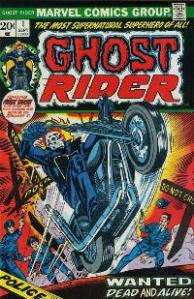

I started reading comics as a kid at a particularly satanic moment. Not only had vampires and werewolves crashed through the gatekeeping Comic Code, but the literal Son of Satan demanded his own title in 1973. My favorite supernatural superhero though was the demonic motorcyclist Ghost Rider. Marvel writer Gary Friedrich said the flaming skull idea was his. In fact, Friedrich said the whole character was and sued a few weeks after Columbia released their first Ghost Rider movie (it barely broke even, so I’m still confused how Nicholas Cage managed a sequel). In the comic, Friedrich wrote about the Evel Knievel-inspired Johnny Blaze signing away rights to his soul to save his adoptive father from cancer. A U.S. District Judge wrote in her court opinion that Friedrich had signed his rights away to Marvel.

It’s a diabolically common comic book plot, dating back to Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster signing DC-owner Harry Donnenfeld’s standard contract and handing their mobster boss Superman for $130. But that wasn’t the first superhero deal with the devil.

When Mephistopheles offered to be Faust’s “servant,” the wizened scholar wisely asked “how must I thy services repay?” demanding “the condition plainly be exprest!” In exchange for his soul (“under-signest merely with a drop of blood”), Faust wanted superhuman knowledge. He’d exhausted all human study—philosophy, medicine, jurisprudence, theology—but was “no nearer to the infinite.” Goethe introduces him alone in his study, moments before conjuring his first spirit:

Therefore myself to magic I give,

In hope, through spirit-voice and might,

Secrets now veiled to bring to light,

That I no more, with aching brow,

Need speak of what I nothing know;

That I the force may recognise

That binds creation’s inmost energies;

Her vital powers, her embryo seeds survey,

And fling the trade in empty words away.

Goethe published the first half of his dramatic poem Faust in 1808, based on the German alchemist Johann Georg Faust who supposedly died in a laboratory explosion when the devil came to collect him personally (the German Church had said the two were in league). An anonymous historian included their actual contract, complete with its legalistic “whereas” and “whereof” jargon, in the first 1587 compilation of the legend. Christopher Marlowe introduced the doctor to English audiences two decades later, but I prefer Goethe’s version. His Faust is the first superman. One of the spirits he conjures asks: “What vexes you, oh Ubermensch!”

Friedrich Nietzsche famously adopted the term, but only after reading Lord Byron’s dramatic poem Manfred while still in school. Young Friedrich called Byron’s Faustian knock-off an “Ubermensch who commands the spirits” and felt “profoundly related to this work,” preferring it over Goethe’s. Byron first heard Faust the summer the Shelleys visited his Geneva manor. Mary Shelley began Frankenstein that same visit, and her mad scientist, like Byron’s mad magician, inherited Faust’s “ardent mind,/ Which unrestrain’d still presses on for ever.” All three o’erleapt the human sphere to know what “Doth for the Deity alone subsist!”

I teach playwriting, so if either poet showed up in class, we’d have to have a very long discussion about the word “dramatic.” Though equally unstageable, Manfred is Faust minus Mephistopheles, a subtraction that probably won over the impressionable Nietzsche. Manfred doesn’t barter his soul to anyone but his diabolical self. His powers were “purchased by no compact” but “by superior science,” “strength of mind,” and a whole lotta “daring.” He accepts his approaching death, but defies “The Power which summons me,” refusing “to render up my soul to” the demonic spirit he orders “Back to thy hell! Thou hast no power upon me.”

Thou didst not tempt me, and thou couldst not tempt me;

I have not been thy dupe, nor am thy prey—

But was my own destroyer, and will be

My own hereafter

The abbot at Manfred’s side urges him to pray for salvation, but Manfred will have none of that either, content to “die as I have lived—alone.” His soul takes its earthless flight, whither the abbot dreads to think. He means Hell, which is where Marlowe sent his Faust in the last act of his tragedy, dragged down like Don Giovanni by the Commandatore’s statue. But the first part of Goethe’s trajedie ends with the repentant Faust’s arrival in Heaven—another reason for Nietzsche to prefer Byron’s ubermensch.

After Manfred, Byron started composing his satiric epic Don Juan, leaping from a damned alchemist named John to a damned womanizer named John. George Bernard Shaw landed in Byron’s footsteps when he modernized Don Juan as an aristocratic eugenicist in his 1903 play Man and Superman—the first time Nietzsche’s “ubermensch” is translated “superman.” Shaw’s John, however, never signs his soul away, just his life when in his last act he submits to marriage—an institution he’d opposed as an obstacle to breeding supermen. He wants to populate the planet with a race of goodlooking philosopher-athletes.

Goethe’s Faust could have demanded invulnerability and super-strength, but his superpowers seem more noble:

The scope of all my powers henceforth be this,

To bare my breast to every pang,—to know

In my heart’s core all human weal and woe,

To grasp in thought the lofty and the deep,

Men’s various fortunes on my breast to heap,

And thus to theirs dilate my individual mind,

And share at length with them the shipwreck of mankind.

Compare that to one of the more recent soul-selling superheroes, Todd McFarlane’s Spawn. When the former CIA assassin died, he made a deal with a demon to see his wife again—and next thing he’s sporting a necroplasmic body with superhuman strength and infinite regenerative powers. He battles angels, demons, and a range of human thugs—but not publishers. McFarlane was one of a group of artists who rebelled against Marvel’s “work for hire” requirement that employees give up all ownership rights—a policy they reversed when they formed Image Comics in 1992. Spawn was one of the company’s first titles.

I applaud their business practices, but when I picked up Spawn No. 8 from a magazine shelf in my local bookstore, I was horrified. It seemed my favorite writer, Alan Moore, had sold not his soul but his signature intelligence when penning the script. But I’m still glad it sold well, and even spawned a movie that grossed more than Ghost Rider. Meanwhile, Siegel, Shuster, and their heirs have spent decades battling the Mephistophelean DC. Their lawsuits kept the Hollywood Superman in Development Hell for a few years—a 2008 judge almost stripped DC of the copyright—but Warner Bros’ lawyer minions always win in appeals. Marlowe sent his Faust shrieking into Hell, but maybe someday the spirits of the U.S. court system will answer his final prayer:

Let Faustus live in hell a thousand years,

A hundred thousand, and at last be sav’d!