No lesser a Christian than Martin Luther understood our predicament: Anyone, he wrote in On Temporal Authority, who tried ‘to rule the world by the gospel and to abolish all temporal law and the sword on the plea that all are baptized and Christian, and that, according to the gospel, there shall be among them no law or sword—or the need for either— . . . would be loosing the ropes and chains of the savage wild beasts and letting them bite and mangle everyone, meanwhile insisting that they were harmless, tame, and gentle creatures; but I would have the proof in my wounds.’

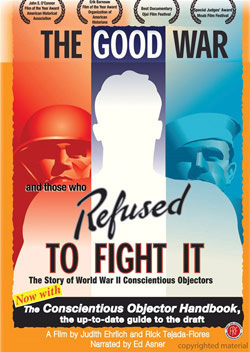

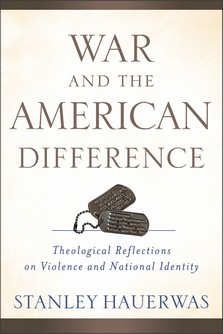

The above is a quote from Eric Cohen’s review of Christian pacifist Stanley Hauerwas’ War and the American Difference: Theological Reflection on Violence and National Identity. Cohen’s review nicely encapsulates the argument against pacifism — that argument being, that pacifism is well-intentioned but dumb, and that it will get us all killed. There are dangerous people out there in the world, and if we don’t use force to stop them, then, well, they won’t be stopped, will they? For Cohen, this logic is so clear that anyone who doubts it must be, literally, crazy. Or, as Cohen puts it, “if Hauerwas’ political theology is the true political theology of Christianity, then Christianity is a form of eschatological madness.”

The above is a quote from Eric Cohen’s review of Christian pacifist Stanley Hauerwas’ War and the American Difference: Theological Reflection on Violence and National Identity. Cohen’s review nicely encapsulates the argument against pacifism — that argument being, that pacifism is well-intentioned but dumb, and that it will get us all killed. There are dangerous people out there in the world, and if we don’t use force to stop them, then, well, they won’t be stopped, will they? For Cohen, this logic is so clear that anyone who doubts it must be, literally, crazy. Or, as Cohen puts it, “if Hauerwas’ political theology is the true political theology of Christianity, then Christianity is a form of eschatological madness.”

Hauerwas would probably accept that designation happily enough — with the caveat that the efficient rationality of modernity is its own kind of madness, what with the gas chambers, the drone strikes, the enhanced interrogation, and the nuclear weapons always on the table.

Indeed, Hauerwas’ point is that war is not simply a natural disaster from which prudent nations must protect themselves with the minimal force necessary. Rather, war is its own logic and its own morality. This, Hauerwas says, is especially the case in America. He points back to Abraham Lincoln’s justification of the Civil War at Gettysburg. Lincoln, of course, said that the war had to be continued in order “that these dead shall not have died in vain,” and further “that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

Hauerwas argues:

A nation determined by such words, such elegant and powerful words, simply does not have the capacity to keep war limited. A just war that can only be fought for limited political purposes cannot and should not be understood in terms shaped by the Gettysburg Address. Yet after the Civil War, Americans think they must go to war to ensure that those who died in our past wars did not die in vain. Thus American wars are justified as a ‘war to end all wars,’ or ‘to make the world safe for democracy’ or for ‘unconditional surrender’ or ‘freedom’. Whatever may be the realist presuppositions of those who lead America to war, those presuppositions cannot be used as the reasons given to justify the war. To do so would betray the tradition of war established in the Civil War. Wars, American wars, must be wars in which the sacrifices of those doing the dying and the killing have redemptive purpose and justification.

“War,” Hauerwas concludes, “is America’s altar.”

Eric Cohen recoils at this conclusion, arguing that

There have indeed been times when we have used massive and terrible power against terrible enemies; and yet, right now, brave American soldiers endure great risk to themselves in an effort to avoid killing civilians. And while the history of America’s wars is hardly a story of moral perfection, it is, by human standards, a mostly heroic story of doing the right thing and doing it for the right reason.

Putting aside for a minute the accuracy of the claim that most of America’s wars have been righteous (the Philippines? Vietnam? the Indian wars?), I think Cohen’s rhetoric here is actually an almost perfect example of Hauerwas’ point. Specifically, from a just war perspective, or from a realist perspective, war surely should be limited and pragmatic, always fought with a consciousness of the tragedy, brutality, and terror which war unleashes. And yet, here is Cohen, responding to that argument, by characterizing America’s experience of war as a “heroic story.” Moreover, that story is not “heroic” despite our history of war; rather, it is war itself that confers upon us heroism. Even our “terrible power” gains a grandeur, since it is unleashed against “terrible enemies” — and never, of course, against children, or civilians. America is moral because of the wars it fights, the ways it fights them — and because of the very terribleness of the conflicts. The obvious corollary is that if we did not fight the wars, we would not be moral — we would not, for example, have the opportunity to exercise restraint by not shooting civilians (except of course, when we do.),

Thus, for Cohen, war provides America with its moral standing and its moral experience; its heroism, its bravery, its sacrifice. This is exactly Hauerwas’ point. War is how America understands itself as a good people; it is how we see ourselves striding across the world stage to protect the weak, avenge the innocent, and establish justice for all.

If any war was fought to protect the weak, avenge the innocent, and establish justice for all, it was the Civil War. Hauerwaus acknowledges the evil of slavery, and insists that Christians were bound to witness against it. He insists, though, that the witness against slavery should not be war; that the moral opposite of slavery is not killing. For Hauerwas, to argue otherwise is idolatrous.

War is a counter church. It is the most determinative moral experience many people have. That is why Christian realism requires the disavowal of war. Christians do not renounce war because it is often so horrible, but because war, in spite of its horror, or perhaps because it is so horrible, can be so morally compelling. That is why the church does not have an alternative to war. The church is the alternative to war. When Christians no longer see the reality of the church as an alternative to the world’s reality, we abandon the world to war.

When I read that paragraph, I thought immediately of that superstar atheist, Christopher Hitchens, and his bloodthirsty reaction to the September 11 attacks.

Here we are then, I was thinking, in a war to the finish between everything I love and everything I hate. Fine. We will win and they will lose. A pity that we let them pick the time and place of the challenge, but we can and we will make up for that.

Hitchens famously denigrates faith…but that’s not exactly a pragmatic, measured, calculus there, dripping with restraint and quiet reason. On the contrary, it’s in the genre of prophetic apocalyptic — it’s a religious statement. And the religion is, as Hauerwas says, the church of vengeance, the church of retribution, the church of death, self-justification, anger, honor, and war.

Hauerwas would like to get rid of war and violence — but what he really wants to get rid of is the church of war. As he says, the abolition of slavery (accomplished in part, of course, through war) did not eliminate slavery. There are still people who are enslaved today around the world. But the anti-slavery movement made it impossible for anyone to justify slavery. The church no longer says that it is god’s will for men and women to be chattel; the state no longer insists that it is righteous for some to be slave and others to be free. The abolition of slavery was the abolition of the church of slavery — and that abolition has had a massive, thoroughgoing effect on how people treat each other on this, our earth.

Hauerwas is asking Christians, specifically, to follow their faith to a similar confrontation with the church of war. He is not saying that all wars will be eliminated, or that all violence will disappear, any more than all slavery disappeared. Rather, what he wants is for the moral underpinnings of war to be systematically knocked out. He’s looking for a world in which Eric Cohen cannot use war to make the United States heroic; in which Christopher Hitchens cannot puff himself up as a savior/prophet in the name of cleansing violence. He’s looking for a world in which war is not the measure of reality or goodness, but rather a sin, indulged in only by those who have deliberately eschewed morality, heroism, faith, and sacrifice.

Again, Hauerwas is definitively, defiantly Christian. His message, therefore, is specifically to Christians. It is Christians, first, he believes, who must determine not to kill each other. It is Christians, first, who must reject the morality of war for the morality of the Cross. On the one hand, this is something of a relief for atheists like myself. Since I’m not a believer, I can cheerfully keep paying taxes for cluster bombs and hating my neighbor just as I’ve always done. Still, there is a bit of discomfort there too. If, after all, Christians were actually to take up Hauerwas’ challenge, if they were actually to bear witness to nonviolence and transform the world — well, I’d hate to say it, obviously, but it would be hard to escape the suspicion that that might actually be the work of God.

Until that day comes, though, we are stuck with war. And since that is the case, it might behoove us all to spend less time questioning the sanity of pacifists, and more time thinking about what this thing, war means to us. Is war our tool, with which we visit justice upon a grateful world? Or, alternately, are we the tools of war, with which it performs the age-old work of violence? Who, in short, do we serve? And is there anything — be it life, honor, love, freedom, or faith — that we will not sacrifice, or have not already sacrificed, in its service?