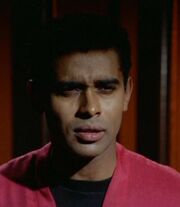

Writing for The Establishment, The Hooded Utilitarian’s own Noah Berlatsky recently penned a devastating critique of one of the special snowflakes of science fiction: Star Trek’s “The City on the Edge of Forever” (1967). Even if you’re not a trekkie, or didn’t watch The Original Series (TOS), you’re familiar with the trope that the plot relies on. Berlatsky tersely characterize the episode as “an elaborate exercise in justifying violence and would-you-kill-baby-Hitler ethics.” That is, in order to save the present, someone who did something evil must die in the past. To the extent that Trek offers a twist on that trope, it’s that the person who must die, Edith Keeler, is actually good.

That amplifies the emotional stakes, sure, though at the cost of the plot and drama, since we know this story can only have one possible ending. And that ambivalence – in Kirk, in the audience – does nothing to undermine the self-evident logic of the trope: the ends of time-travel will justify even the most otherwise unconscionable means.

It doesn’t have to be this way, of course. The “kill baby Hitler” trope, also known here on the interwebs as the “Set Right What Once Went Wrong” trope (SRWOWW), is ubiquitous among science fiction serials. (So much so that the 80s saw both a TV series and film franchise about this exact plot-device: Quantum Leap and Back to the Future, respectively.) So, too, are variations on it, most of which fall into one of the following categories – exercises in hubris where the results actually make things worse, fixed time loop universes where change is either impossible or semi-fixed, ironic iterations where the would-be assassins actually cause the event they’re trying to stop,and scenarios where the effects of any changes remain unknown or unknowable. To touch just the tip of the iceberg.

What allows Kirk and Spock to act with moral certainty, despite the seeming immorality of the individual act itself, is a feature that’s unique to science fiction and time-travel stories more generally: perfect knowledge of the past and its relationship to the future, of cause and effect.

[I write “unique” because this is not the same as the claim that we have access to perfect foresight and knowledge of what will happen in the future. Even when the Bush administration claimed to know that Saddam had weapons of mass destruction that he would use against his enemies – which he didn’t and thus wouldn’t, as it turned out – they could never be absolutely certain. And this is why the trope is particularly insidious and the distinction between the fictional and the real is particularly important: when we invoke the logic of SRWOWW – we know this thing will happen and so we must do this other thing to prevent it – in real life, we erase that difference. We start to believe that we, like Spock, have access to perfect knowledge and awareness of the future. Spoiler: we don’t.]

This perfect knowledge? It’s artistically and politically irresponsible. It also saps the story of a great deal of tension. It’s just pain lazy. But it should be remarkably easy to fix.

Imagine if, rather than perfect knowledge of 1) the event that would change history, and 2) its effects in the future, Kirk and Spock only knew one of these things? Or perhaps neither? If Kirk and Spock know that Keeler should – from their perspective, anyway – have died but can’t know whether the world will be better or worse for it, their decision becomes considerably harder. In fact, it problematizes the kneejerk use of the modal “should”. Even if she died in their past, why does it follow that must die in this one? And could the world, in fact, be a better place for her presence?

Likewise, if they know that the future has changed in some significant way but can only guess at the cause of that change, their mission becomes a detective story that possibly reaches no concrete conclusions, only descending into a far more ambiguous morality tale if and when they figure it out. If and when they think they’ve figured it out, that is. Knowing that they can’t be certain, how confident must they be in order to justify the murder of an innocent person? And for that matter, must she die?

This got me thinking: given the love for this episode, we might assume that Star Trek would follow its formula and logic in the future. But did they? And if they didn’t, did they manage to improve on it? What follows are some reflections on what I deem to be the most creative and thoughtful exercises in time-travel logic and ethics from each of The Next Generation (TNG), Deep Space Nine (DS9), and Voyager (VOY). And the first post-TOS time-travel story, for what will be some obvious reasons.

TNG – Yesterday’s Enterprise (3×15)

The Next Generation’s first time-travel episode, originally pitched with “The City on the Edge of Forever” in mind as its inspiration, is probably the series’ – if not all of post-TOS Trek’s – most infamous and best-loved time-travel story. It’s been cited by Roberto Orci as an inspiration for the rebooted Star Trek and repeatedly voted one of, if not the best, episodes of TNG. People like it, is what I’m saying.

“Yesterday’s Enterprise” has a pretty simple premise, but one that’s surprisingly hard to explain. The previous iteration of the Enterprise, from 22 years in the past, ends up in the present when it passes through a rift in space-time. As a result, the present immediately changes – the Federation is at war with the Klingons, and they’re losing. Only Guinan knows that something has changed, and even though she can’t explain why, she must convince Picard to send the Enterprise of the past to their deaths in the past.

Our first example of SRWOWW in TNG, and it provides a small twist on the model provided by “Edge of Forever.” Do we know of both the specific event that will “fix” the timeline and the effect that it’ll produce? We do, yes, because we’ve been watching the show for 3 years and we know this isn’t right. That much is pretty straightforward.

But the characters? They don’t. Sure, Guinan has some awareness that something is wrong, and that skirts uncomfortably close to a reading of the regular timeline as a timeline of destiny. But Guinan can’t explain why and the decision becomes simply a calculated risk. Maybe the Enterprise C can make a bigger difference in the past than the present. Maybe the C will survive the battle in the past. Maybe it’s even worth sacrificing the Enterprise D, given the way the war with the Klingons is going. Maybe.

I’m stretching, though. We know what Picard needs to do, and we know what’ll happen if he does it. That’s a sort of dramatic irony, I suppose, but not as different from “Edge of Forever” as it first seemed.

TNG – Tapestry (6×15)

There were plenty of episodes with time-travellers, time-loops, and temporal anomalies between “Yesterday’s Enterprise” and “Tapestry”, but none where the crew was forced into any serious ethical dilemmas. “Tapestry” begins with Picard’s ostensible death, the captain having been shot in the chest and, as a result, his artificial heart exploded. Q gives Picard the chance to re-live and change the past, thus avoiding the bar-fight that damages his fight and saving his life in the present.

Things don’t work out the way Picard hopes, though. It turns out that the fight was a defining moment of his life – the loose thread that unravels the tapestry of the episode’s title – and so the pacifist Picard leads a totally undistinguished life. Dejected and disgusted with himself, Picard tells Q that he would prefer to die as the man he was, rather than live out his life as a timid and unremarkable astrophysicist.

Like “Yesterday’s Enterprise”, “Tapestry” offers a small twist on the SRWOWW model – Picard knows what must be done, but he doesn’t know what it will change. That the alternative life is unbearably dull is a surprise, but Picard doesn’t hesitate to reverse his decision. As it turns out, of course, he didn’t actually die.

It’s an easy choice, from a story-telling and audience perspective, for Picard to restore the universe as we know it. We know this to be the correct timeline, the real one. The one where Picard doesn’t fight? Simply put, it’s wrong. And given how Picard stipulated to Q that nothing could change except for his own life, it doesn’t just feel wrong – it feels artificial.

But should it have been an easy decision? The resolution leaves me with an uneasy feeling. Picard decides that living an average life is, essentially, not worth living. He chooses death and a short but exceptional life over, well, something more like our own lives. Is being unexceptional really so bad? It would seem so, yes.

DS9 – Visionary (3×17)

This isn’t DS9’s first time-travel story – that title belongs to “Past Tense” (3×11/12), a social justice story where the time-travel element is set-dressing, rather than central to the conceit. But “Visionary” is probably Star Trek’s most fascinating and thoughtful time-travel episode, though the actual time-travel that’s involved is rather modest by comparison to the other stories in this list.

Radiation poisoning keeps sending Chief O’Brien several hours into the future. While at first just peculiar, this turns out to be very fortuitous, since it allows him to prevent both his own death and the destruction of the station. The plot is an elaborate detective story, with the crew of DS9 trying to figure out why O’Brien is shifting in time and how to stop it (and then restart it) even as they use his knowledge of the future to change it. In an added wrinkle, their actions to change the past also shifts the goalposts, as O’Brien’s time jumps reveal an altered but no less problematic future.

In a unique twist on SRWOWW, given that every other iteration to this point saw reality restored to what it once was, the iteration of O’Brien that we’ve been following this whole time dies from radiation poisoning in his final jump to the future. Knowing that he won’t survive the return trip to the past, this O’Brien sends his alternate-future-self – who is likely to otherwise die in a Romulan attack on the station – back to prevent his own timeline from being formed. In doing so, he’ll both replace and erase the “original” O’Brien, who remains in the about-to-be-erased future. It’s a mouthful to explain, but trust me: this is mad, disconcerting, and moving stuff.

In the final act, after Doctor Bashir alone has realized that the wrong O’Brien came back, this “new” O’Brien confesses that he feels like he’s living another man’s life. Bashir disagrees, arguing that he’s the same man but with just a few extra memories. It’s a subtly unsettling resolution. But why should it be? Bashir’s technically right, but doesn’t O’Brien’s point simply feel somehow more valid? It’s ultimately a very small detail, but it’s one that lingers.

VOY – Relativity (5×24)

The Voyager crew dabbled in time-travel almost immediately, considering a trip 20 years into the past in the entirely unconvincing “Eye of the Needle” (1×07). It didn’t get much better from there, unfortunately, though it would get much, much more confusing.

Relativity is a mess, both with respect to plot and time-travel logic. It seems to be using DS9’s “Visionary” as a model – Seven is being moved in and out of the timestream in order to save Voyager from a sort of time-bomb of unknown origin. These same travels are gradually killing her, somehow, but this is really the least confusing detail in the story. The surprise reveal of the villain, a future version of the same 29th Century timeship captain, Braxton, that sends Seven on this mission in the first place, is more baffling than it is alarming.

The episode does do something brand new, by adding the bizarre new concept to “reintegration” to the Star Trek universe. Rather than wiping a timeline completely so that, for instance, Braxton or Seven don’t simply forget certain events but have literally never lived them, we’re told that these versions who have now never existed and exist only outside the timestream will be reintegrated with their current selves. They’ll be combined with the person who properly belongs to the new/restored timeline. This other version of the character, once blissfully unaware, will be combined with and/or remember what the out-of-timeline character has done. Why? How? Huh? It’s an unnecessary and silly detail, and it also cheapens earlier episodes like “Visionary”, which discomfort our assumptions of belonging to a place and time, and even our own sense of uniqueness, without completing obliterating them.

“Relativity” is also a bit too self-conscious and precious. The villainous future future captain is making his second appearance on VOY, which also happens to be the second episode where he’s gone mad and declares Janeway his mortal enemy. There are also numerous, half-joking references to Janeway and the ship’s repeated travels through time and changes to the timestream. Time-travel, like encounters with the Borg, is getting awfully familiar and gimmicky at this point in VOY’s tenure, and the creators know it.

By the time the finale of VOY, “Endgame” (7×25), rolled around, time-travel in this series had become both ubiquitous and virtually meaningless. The finale appeared to follow no coherent set of time-travel rules, and knowledge of the future was seemingly employed entirely as a vehicle to tie-up every loose end and make Voyager’s win over a previously unbeatable enemy seem somehow possible. Fittingly, I suppose, in VOY’s finale a future Admiral Janeway traveled back in that episode to kill her own Baby Hitler – the Borg Queen. No questions or ethical dilemmas, here. And not even the over-rated gravitas of “Edge of Forever”. If Star Trek did learn anything from that episode, they also soon forgot it.