“I have the power to drop into the Fold,” Arno Strine tells us on the first page of his autobiography. All he has to do is push “my glasses up on my nose Clark Kentishly,” and “I am alive and ambulatory and thinking and looking, while the rest of the world is stopped.”

It’s an unusual superpower, one possibly due to his being born with a knot in his umbilical cord which required him “to form a loop and then pass right through it.” Also his job transcribing taped dictation, “starting and stopping so many thousands and thousands of modest human sentences-in-progress with my foot-pedal,” may have honed his time-pausing powers.

Being “a thirty-five year old male temp who has achieved nothing in his life” is a pretty lackluster existence for one of the most powerful human beings on the planet. But like so many who maintain alter egos, Arno wants to keep his superpowered life “a secret, and as a result it has swallowed up large chunks of my personality.” What superhero can’t relate?

Aside from a couple more intentionally bogus origin stories, Arno does purport to being “guided by a will greater than my own” and even theorizes “the reason I have been chose over any other contemporary human to receive and develop this chronanistic ability (if there is indeed some supernatural temp agency doing the choosing) is maybe that I can be trusted with it.”

And for the most part, Arno really is a trustworthy guy. “Fear” is his “least favorite emotion,” and he wants “to be responsible for creating as little of it as possible.” He doesn’t even like using his powers against his own would-be muggers, and as penance he spends an afternoon “performing acts of lite altruism,” including “collecting concealed handguns off anyone who looked under thirty” and disposing of them (forty-four in all) in newly poured cement.

“I have never deliberately caused anyone anguish,” Arno reports. He literally wouldn’t hurt a “grub” or want to cause “trouble for any living thing.”Or, for that matter, a non-living thing such as the bookstore paperback he purchases because he wrote in it while in the Fold. Other would-be Fold-users might enrich themselves as spies and thieves, but he can’t bring himself to steal a dollar from a cash register. He sincerely wishes to do no harm to anyone. “The last thing in the world I want,” he tells us, “is to be seen as a threat.”

So what’s this swell guy’s one and only downside?

He’s a rapist.

Or, to be fair, he’s something that doesn’t have a name. Because what do you call a man who while in the Fold, undresses women, gropes them, and, in at least one case, ejaculates on their unaware bodies?

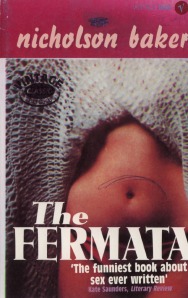

It was not, by the way, a supernatural temp agency who bestowed Arno’s “time-perversion” powers. It was Nicholson Baker. Arno doesn’t live in a comic book or, more plausibly, a Penthouse comic strip. He’s the narrator of Baker’s 1994 novel, The Fermata. (That’s just two years before the collapsing Marvel Comics finally filed for bankruptcy protection after farming its pantheon to temps, and so a fitting backdrop for such a morally bankrupt novel.)

Which is not to say The Fermata (another term for the Fold) is a bad novel. Baker is an excellent writer (my wife teaches his Lovecraft homage to gothic potatoes), and when not falling victim to the contrivances of their pornographic plots, Arno and his fellow characters are rendered with stylistic brilliance.

But, unlike Oscar Wilde, I do believe art can also be judged in moral terms. All art is propaganda, and The Fermata advocates for a way of thinking that gets a lot of women raped.

University of Rochester Professor Steven Landsburg recently blogged in response to the rape conviction of two high school football players in Steubenville, Ohio: “As long as I’m safely unconscious and therefore shielded from the costs of an assault, why shouldn’t the rest of the world (or more specifically my attackers) be allowed to reap the benefits?” Landsburg notes that the “Steubenville rape victim, according to all the accounts I’ve read, was not even aware that she’d been sexually assaulted until she learned about it from the Internet some days later.” Since there was “no direct physical harm – no injury, no pregnancy, no disease transmission,” Landsburg asks, “Ought the law discourage such acts of rape? Should they be illegal?”

Students of Rochester have answered with a resounding YES! They are protesting outside Professor Landsburg’s classroom and petitioning the administration to censure and/or fire him.

According to national statistics, at least 1 in 4 women are sexually assaulted while at college. My school’s rate probably isn’t much higher. Though when the women in questions are the ones sitting in my literature classes, the statistic isn’t abstract.

Their male assaulters sit in front of me too. They seem like good guys. In fact, they are good guys—friendly, bright, engaged, funny, sincere, all-around well-intentioned young gentlemen who on occasion will rape their fellow classmates.

By rape I mean, for the most part, render unconscious and sexually penetrate. A behavior which, amazingly, horrifically, unfathomably, they do not register as morally repulsive. Somehow many of these young men do not realize that sex with an unconscious body is not sex. They do not understand that sex without consent is rape. Or, more accurately, they do not wish to understand.

Which brings us back to Arno.

Basically the Fold is a super-roofie. One he’s employed on “hundreds” of women. Arno’s ex-girlfriend likened his behavior (or would-be behavior, since Rhody thought he was only divulging a fantasy—which was reason enough for her to dump him) to necrophilia. She found it, and so him, “repellent,” deserving to be “criminally prosecuted.” And Arno knows it’s true. He “would condemn in the strongest terms anyone else who did what I have done.” In fact, “when I try to imagine defending my actions verbally I find that they are indefensible, and I don’t want to know that.”

And yet he spends some 300 pages detailing those exploits, acknowledging the “self-deception” that allows him to commit them. Basically he’s a tidy pervert, meticulously cleaning up afterwards, restoring every fold of clothing to its precise position, so the female wearer is in no way aware of or troubled by the events she did not witness. And his concern seems genuine. We have every reason to believe him when he declares: “I want above all for women not to cry.”

This is a kind of duality outside most superhero tales. I don’t know how Nicholson Baker would render the self-deluding mindset of a W&L rapist, but the mental gymnastics of willed ignorance must approach the superhuman. And on the moral scale, Arno is a step up: “I could never get interested in a woman who was passed out drunk, or was sedated, in a coma, or dead.” His victims don’t wake up hungover. They don’t suffer from disturbing half-memories and chunks of lost time. They never suspect a thing.

In Arno’s defense, he never ogles women when not in the Fold because he would never wants to make anyone uncomfortable. His moral duality is also nothing like the security guard who proudly shows Arno photos of his wife and kids while describing how he would use the Fold to drag a “mint chick” into an alley, turning time on and off so he can feel her fighting as he’s “hammering the shit out of her.”

“But that’s rape,” says Arno.

“Right.”

Baker, if you haven’t noticed, is toying with us. And I don’t object to the moral puzzle of his conscientious sex offender narrator. I don’t even object that Arno goes unpunished and forgiven. I like forgiveness. Arno finds his in Joyce, a woman he dates only after admitting to her that he ogled and fondled her unaware body. She’s pissed at first, but deals with it. (Note that Baker does not have Arno attempt a confession/apology with the woman with whom he rubbed naked anuses before ejaculating into her face.)

No, I’m pissed at Baker because he allows Arno to go unredeemed. Unlike Nabakov’s Humbert Humbert, Arno doesn’t even know he needs redemption. And neither does his new girlfriend. Joyce, it turns out, is a like-minded sex offender, who (when Arno accidentally transfers his powers to her) carries on his legacy, exposing and groping at will.

A reader—say, for example, one of my well-intentioned sex offender students—might set the novel down thinking he’s just read an oddly literary, essentially harmless bout of erotica. I’m told Frat house TVs here spin porn 24/7, so Arno’s Fold adventures may seem comparatively quaint. And since Joyce and Baker let Arno off the hook, that lost male reader might think he’s off the hook too—even though, like Arno, he must know he’s not.

What kinds of damage does unexamined guilt inflict on a psyche? What new kinds of damage will a guilt-Folded rapist continue to inflict on victims while trying desperately “not to know”?

These are moral puzzles Nicholson Baker didn’t find time to ask.

Professor Landsburg, however, is rethinking (and/or massively clarifying) his own moral puzzle.

He recently wrote that “some readers might have thought [my original post] was an argument for rape. It wasn’t; it was an argument against,” specifically the legal idea that “You can do anything you want as long as you’re not causing anybody direct physical harm,” because that reasoning would “allow you to rape an unconscious victim if there were no physical consequences. That seems grotesque, so this rule seems wrong.” The reason he mentioned rape at all, he explains, “is because rape is particularly bad, so we can be quite sure we don’t want to adopt a rule that might allow it, even in the extreme hypothetical case with no physical damage. In other words, it’s mentioned because it’s horrible.”

Thank you, Professor.