:origin()/pre10/f1b4/th/pre/i/2012/179/a/a/iron_giant___superman_by_r0b0c-d555hpu.jpg)

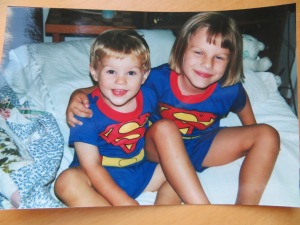

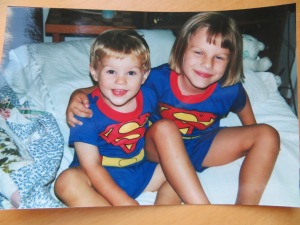

It wasn’t my fault. It was the Iron Giant’s.

Do you remember how you adored that movie? The kid hiding the alien robot in his barn left some old comics out and the robot read them, or flipped through the pictures at least, fell in love with the caped man flying across the covers. The video played continuously in our living room while your mother battled false labor.

You longed for a Superman comic of your own. There were rotating racks everywhere when I was a kid, but I finally chased down an Action Comics in the bottom row of magazines in our mall CVS, Teen and Tiger Beat poised perilously close. You opened it across your foot-high table, shoving aside plastic ponies and teacups to make room. “He uses his powers only for good,” you said.

After your brother’s birth I rented the 1978 Superman, something a father and a recovering mother can watch with their three-year-old daughter. I was twelve when it came out, already invulnerable to PG ratings, but now I punched the forward button when I remembered a cop getting shoved in front of a train. It wasn’t the mangled impact, but the idea of it, the roaring tracks, the vanishing body. You were irate.

“It’s okay to die,” you said. “That’s what the boy in The Iron Giant says.”

It was true. The robot sacrifices himself to save the kid, to save the whole town, shouting “Superman!” as he rockets into the oncoming warhead.

“When you’re grown-up,” I said, “you can decide for yourself, but while you’re little, Mommy and I have to.”

That was enough, that glimpse of your future self, a promise. The bad parts could wait. The next day you called me in a dozen times to fast-forward the boring bits too.

You found Batman on your own, a two-page cameo in that Action Comics, and asked who Superman’s friend was. I left out his parents getting gunned down in an alley outside a movie theater. The age seven TV rating worried me, but you and your mother started watching the cartoon before bedtime. You called his villains Kittycatwoman and Tutuface and pretended your floppy-necked brother was Scarface, the evil puppet. The bat costume for Halloween was pure coincidence. You wore it to the grocery store the day it arrived, admiring your bent ears, your scalloped wings, the gray felt of your belly.

Christmas came early. An uncle mailed you a Batman doll on my advice, and you gasped when you opened it, declaring how you had always wanted one and had waited so long and now you finally had it. You wowed the boys at show ’n’ tell, tucked him under a pink blanket, hung his cape in your toy barn, said he needed tap shoes. You wanted Superman even more. At night you dreamt of flying on his back.

“Superman should sleep with me,” you said. “Batman should sleep with Mommy, and Daddy can sleep with Robin.”

The Superman franchise was gestating between projects, so there was no doll to be found here or in neighboring towns, not even on Etoys or Amazon. Ebay listed collector items, ancient toys that had never escaped their packaging and never would. Your mother warned that Santa might not be able to find you a Superman, but you explained that he and his witches could make one. Santa, you warned your other dolls, can see them, though you sounded skeptical; you knew Superman’s x-ray vision was pretend. Your mother helped you write Santa a letter after I found a late ’80s version, with imitation rips in his plastic cape inflicted by a cyborg named Metallo, the villain the Iron Giant would rather die than become. She wrapped it in special Santa paper, to distinguish it from the mound of gifts coming officially from us. The ’40s and ’50s Superman videos arrived late.

You still dreamed of sleeping in his arms. Mornings you explained how he followed you downstairs and was hiding behind the couch because it was time for school. Batman was naughtier. He woke everyone up, so you had to tape his mouth shut. Your new Joker doll had a fistfight with Buzz Lightyear, but usually everyone got along, hugging, reading tiny books, gathering for tea parties, napping in all corners of the house.

I read you books, and I drew pictures with you: unicorns, dinosaurs, superheroes. You asked if Superman would ever die. You didn’t want to, you said. Family friends had just cancelled a playdate after a grandfather’s heart attack. One of your ponies succumbed the next morning; it lay on the kitchen tiles where you dropped it. “My granddad didn’t die,” you clarified.

When I tucked you into bed and rubbed your back, you told me you hadn’t decided yet whether you were going to leave our house when you were older. I promised you never had to.

“Even when I’m a grown-up?”

“Even then.”

I left your lamp on, the one I’d screwed a low-watt bulb into after a nightmare the week before. You said you’d thought there was a monster in the next room but that there wasn’t. Your longest and saddest life complaint was not having anyone to sleep with, not even a kitten to cuddle. You were in tears at your cousins’ because everyone else was two in a bed. You talked about sleeping with Batman and Superman, the way your mother and I got each other every night. Your brother could have Batgirl.

He needed shots at his four-month check-up, and so did you. We didn’t tell you till the nurse appeared with the needle. You always got so traumatized imagining what was coming that we thought a warning would have been crueler. I held you still in my lap as you screamed. Then your mother handed you the Spider-Man doll she’d bought that morning because the Batgirl she’d ordered was late. We were all amazed. Batman marched stiff-legged, Superman could bend knees and elbows, but Spider-Man used even his ankles and wrists, like a mechanical body transforming incrementally into a live one.

We had weaned you from evening Batman, because of those nightmares, but when you opened to a picture of the Justice League in TV Guide, you ran up the stairs shouting for me. You made me list every superhero in flying and non-flying categories. You theorized a tiny Superman was hiding inside Green Lantern’s ring. Easter morning exploded with your yelp when you unearthed the Batman T-shirt from the plastic grass in your basket, a partner for the men’s sized Superman tee you wore as a shin-length nightgown. The Easter Bunny, you said, was really a person in a costume who came to our house and hid eggs. Your mother tried to explain Jesus to you, the crucifixion, the resurrection. I pictured the Iron Giant in the final scene as his globe-scattered body parts rolled and beeped their way to the North Pole where he was patiently rebuilding himself.

The next Christmas you studied the manufacturing marks on the soles of your superheroes, irritated they were all made in China. You still let the entire seven-member League sleep in your bed for a week or two, before moving them into your dollhouse. You even spent your own allowance money on a Justice League coloring-activity-sticker book, a savior during snow days. But by spring, your heroes had migrated to your brother’s rug or attic boxes. Batman’s ears were chewed down, his mask dented by the baby teeth that I still keep in a jewelry box in my sock drawer. When Barbie launched a new line of superheroines—Wonder Woman, Supergirl—the Superman T was climbing up past your knees.

“If I only had one day to live,” you announced one afternoon after kindergarten, “I would watch Justice League and play with Lego.” You’d been studying the one-day lifespan of a bumblebee.

Justice League was only on Saturdays at noon, a weekly lunch date. When it went off the air, we rented the ’70s Wonder Woman, tuned in for Teen Titans and Who Wants To Be a Superhero, but you were as happy in a corner with a book or conspiring with friends in their faraway houses. I’d helped you conquer your bike, and now you could pedal wind across your own face. You were too big to hang on to an uncle’s shirttail, pretending it was Superman’s cape. You had changed rooms, houses, whole towns. You didn’t want to be given dolls; you wanted to make them. Your Human Torch was marker-dabbed cotton swabs, Invisible Woman a skeleton of paper clips with a cellophane force field. Raven, the brooding, dark-eyed Teen Titan who rebelled against her demon father, was your last game of dress-up. You liked twirling the black cape. You hunted down the website yourself and kept clicking that hip theme song, retro sixties style with Japanese accents. You tolerated Superman Returns but delighted over Bend It Like Beckham.

Your Wonder Woman calendar flew through its months. Next thing you were earning your own money battling the neighbor’s toddlers while she nursed her newborn. One called you “Poopman,” the same way your brother used to mispronounce Superman. The other demanded you build him a Batman house from his blocks, then smashed it and screamed at you to do it again the right way. Mornings I still read books to you and your brother at the breakfast table, Tarzan, Zorro, Dr. Silence, the Night Wind, century-old heroes, part of my research into the lost origins of the genre. The Superman nightgown had appeared in my pile of summer T-shirts. You were going to your first school dance and debated clothing options with your mother, costumes to hide your transforming body. I started Doc Savage, described the Gray Seal, but you asked if maybe we could try something other than superheroes for a while?

If unobserved, you and your bookish friends would still play “Powers” by the creek. You were all sisters, each gifted with control of an element. The bossy one always grabbed water, and you settled for earth, poked your stick in the mud. She could make giant whirlpools appear, but if you declared an earthquake, you were silenced for being unrealistic. The real battle was deciding which pairs were born twins, and then woe to the odd-numbered girl. What mattered most to all of you, though, was being orphans.

You were still hiding your new body in old shirts, preferring things baggy, not to be admired. You wanted to be invisible. You didn’t care about wowing the boys. Then one evening you turned to me in a restaurant parking lot and asked, “What does ‘apocalypse’ mean?”

I wasn’t startled. You wrote vocabulary words on your bookmarks to quiz your mother about later. “The end of the world,” I said. I pictured Krypton.

“But does it have another meaning, like if something is just weird?”

You had commented on someone’s girly blouse that day, had called it “cute,” and one of the popular girls, a former playdate friend, had blinked in shock: “It must be the apocalypse.”

You picked out some snazzy ballet slipper-style shoes that month, a fashion trend invisible to me. You asked for contact lenses to reveal your eyes. Mother-daughter shopping adventures followed, as I sorted strange new garments from my laundry basket: bras, halter tops, fitted tees.

I insisted on one more superhero story, a newly published novel, Austin Grossman’s Soon I Will Be Invincible. One of the two narrators is an evil super-genius, trapped in the social politics of a super-powered middle school. Your science teacher had just emailed to say you’d scored the highest grade in the class, the whole school, his career practically. In English, you startled your entire class by bellowing a supervillain laugh from a line of your own poetry:

“MWAHAHAHA!”

But you preferred the other narrator, the amnesiac cyborg. She doesn’t remember walking in front of a moving truck, the mangled impact, her vanishing body. I tried to read a certain paragraph aloud but kept choking, kept pinching my wet eyes shut. You and your brother peered up from your breakfast plates. You’d recently reclaimed that Superman tee and were wearing it to bed again with mismatched pajama bottoms. I had to hand the book over to you, the only way it would ever be heard aloud. You read with a question in your voice:

“When I think of the photograph of the girl I used to be, a stranger now, I think how much I miss her, and how she was never really happy in the first place … Maybe not everything changes for the worse. Maybe I just became what I needed to in order to survive. I miss the girl I was, and I wish I could tell her that … I bet she never dreamed she would live so long, or do the things she can do now. I wish I could tell her what she’d grow up to be, how strange and beautiful and unexpected she’d be. She’d probably feel a lot better if she knew. The sky and the stars are brilliant, and I think of how much she would have loved this.”

We used to take daily walks, pushing your infant brother in his stroller to the end of our dead end street, the one we left behind with the old house. I would tell you stories that turned into a chain of questions, and you would answer each. Where did Superman come from? What happened to Krypton? Who found his rocket? A catechism, your mother said.

Did I ever tell you Superman’s costume was made from his baby blankets? Have I ever said you are as miraculous right now as you were thumping your fists inside your mother’s gut? Growing up isn’t dying. I’m not mourning you—I’m mourning myself. As his world crumbled under him, Superman’s father tucked his child into a spaceship and sent it rocketing into its own oncoming future. You have your own planets to conquer. The yellow sun will make you strong, keep you extraordinary. It’s okay. You’re not supposed to come back.

[This essay was originally published in Brain, Child Winter 2010. Madeleine leaves for college next week.]

:origin()/pre10/f1b4/th/pre/i/2012/179/a/a/iron_giant___superman_by_r0b0c-d555hpu.jpg)