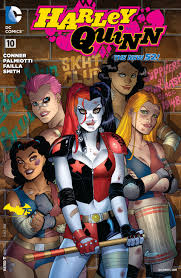

“The comics industry,” according to Vulture.com’s Abraham Riesman, “is in the midst of a golden age for admirable female role models,” declaring the monthly best-seller Harley Quinn “the superhero world’s most successful woman.” I don’t care to dispute either claim, but I will say this isn’t the first such golden age. The “morally questionable” Ms. Quinn descends from a line of female sidekicks turned leading ladies.

Crowbar Nancy lived on an affluent cul-de-sac in Pittsburgh in the late 1940s. She’s not a comic book character. She got her nickname for bludgeoning my mother in the head. They were both ten, or there about, and it wasn’t really a crowbar. The wrought-iron post she yanked from her front fence must have been loose already. My mother had no idea why Nancy hit her with it. They lived katty-corner, though they weren’t friends. Nancy didn’t get along with kids in the neighborhood—a result of being adopted, my mother theorized. The violent streak didn’t help either.

After the crowbar incident (and almost certainly a behind-the-scenes parental negotiation), my mother was invited over to share Nancy’s most cherished possessions. Her comic book collection. Instead of roller skating and hopscotching up and down the block with other kids, Nancy preferred the company of four-color pulp paper. Comics meant nothing to my mother, but she accepted the invitation (or her mother accepted it for her) and across the street she went.

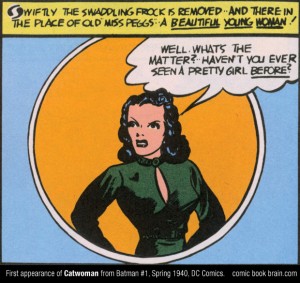

Nancy displayed her trove on her porch for the private viewing. If she was anything like my ten-year-old self, she arranged them in a double row of tight stacks, organized in an idiosyncratic ebb and flow of titles and genres. My mother was born in 1939, same as Batman, so this is probably 1949. DC had long imposed editorial restraint on Bob Kane and his crew, so Nancy’s propensity for clubbing fellow children had nothing to do with the body count of the caped crusader’s earliest adventures.

It wasn’t till 1954 that Frederick Wertham linked the Brooklyn Thrill Killers—four teens who murdered vagrants in Brooklyn parks—with comic books. The gang leader ordered his whip and costume (he dressed as a vampire while flogging women) from ads in Uncanny Tales and Journey into Mystery, titles that Atlas Comics (formerly Timely, soon to be Marvel) debuted in 1952—in imitation of an already deep market trend.

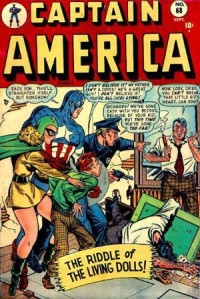

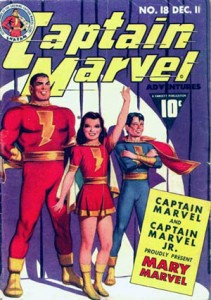

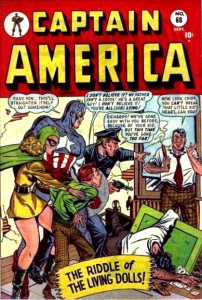

Superman was popular with the Brooklyn gang too, but the Man of Steel was one of the very few cape-wearers still flying. No Timely heroes saved those Brooklyn victims because none existed. Over thirty superhero titles vanished between1944 and 1945, another twenty-three in 1946, and twenty-nine between 1947 and 1949—including former newsstand champs Flash Comics, The Green Lantern, The Human Torch, and Sub-Mariner. Sales for Captain Marvel Adventures, top superhero comic during the war, were down by half. Nancy could have spent her most recent dimes on the final issues of Marvel Mystery Comics and Captain America Comics—before both converted to horror the year she took a crack at my mother’s skull.

But let’s give Nancy the benefit of the doubt and assume her collection did not include the very earliest horror titles (Spook Comics 1946, Eerie 1947, Adventures of the Unknown 1948) either. It was another new trend my mother would have noticed as she reluctantly perused the porch gallery:

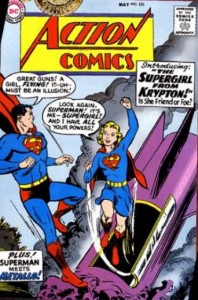

Romance, a new category for comics, was already claiming a fifth of the market. When William Woolfork’s inherited Superman from the recently fired Jerry Siegel (he and Joe Shuster lost their lawsuit against DC for rights to the character when their ten-year contract expired the year before), his scripts refocused the former world-saver around love plots. If my mother leafed through Nancy’s Superman #58 (May-June 1949), she would have skimmed the episode “Lois Lane Loves Clark Kent!” where a psychiatrist tells Lois she must transfer her “love for Superman to a normal man!” Or Superboy #5 (November-December 1949), the adolescent Kryptonian falls for his first girl in “Superboy Meets Supergirl,” the first of many Supergirls to follow.

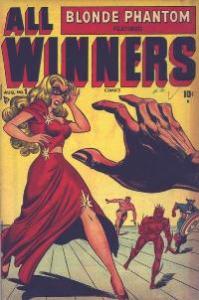

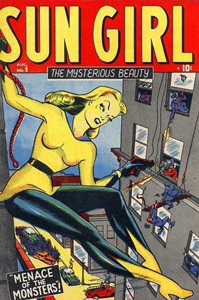

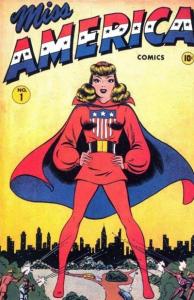

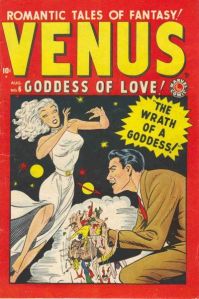

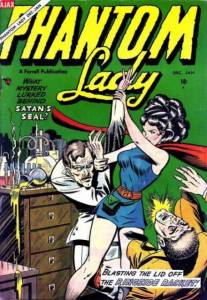

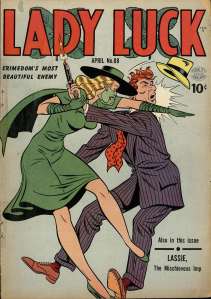

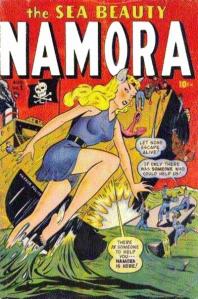

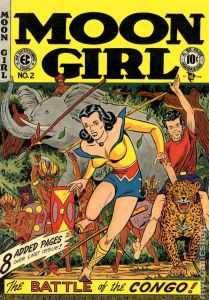

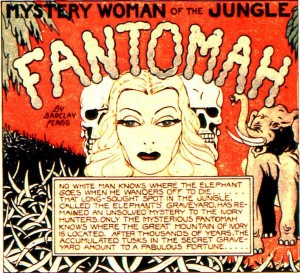

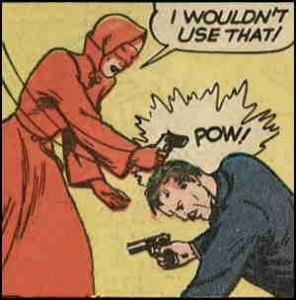

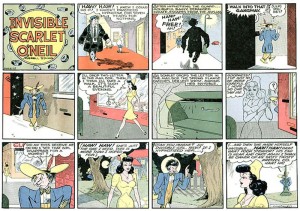

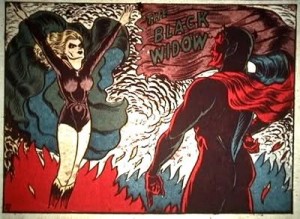

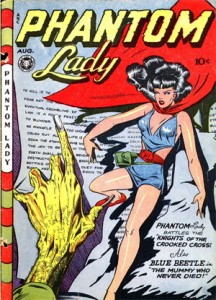

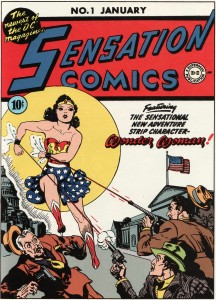

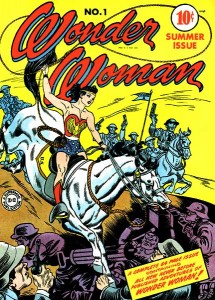

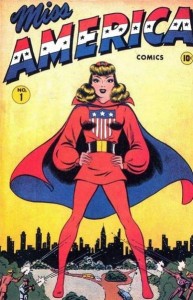

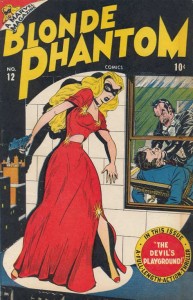

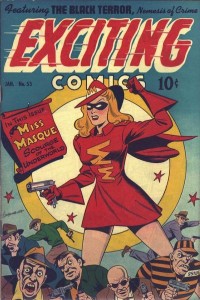

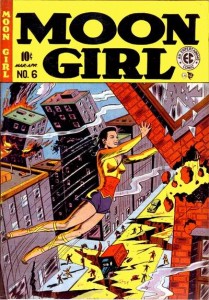

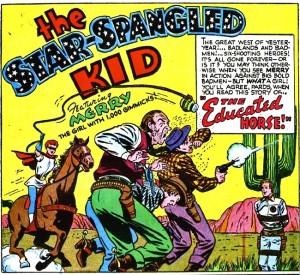

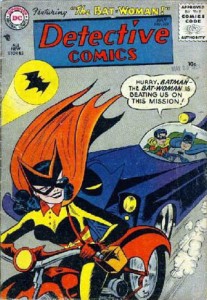

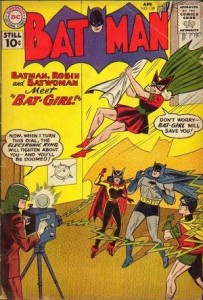

Though only eight new superhero comics debuted between 1947 and 49, five of them sported high heels. Superheroines were on the rise: Black Canary, Namora, Lady Luck, Venus, Phantom Lady, Miss America, Moon Girl. The Blonde Phantom towers over Captain America, Sub-Mariner and the Human Torch on the cover of the new 1948 All-Winner Comics. If there was a doubt about the veiled sexuality between male superheroes and their bare-legged protégés, Timely incinerated it when they fired their top two boy wonders and replaced them with women. Bucky got the boot first, when Golden Girl took over as Captain America’s sidekick in 1947. She even boasted those adorable little wings on her mask, same as Cap’s. The Human Torch’s personal secretary, Sun Girl, replaced little Toro the following year. The Blonde Phantom’s alter ego played personal secretary to her boss crush too, a private investigator who only had eyes for her when—the irony!—she was masked. Or maybe it was the tight, red dress. The leg slit and cleavage were as effective as a blow to the head.

None of this made much impression on my mother. She was the female sixth-grader the romance market coveted, but when she stepped off Nancy’s porch and into puberty, she left those brief, wondrous superheroines behind. Namora’s three issue run didn’t make it into 1949, Blonde Phantom Comics switched titles in May, and Golden Girl exited in October. EC’s single issue Moon Girl and the Prince became Moon Girl Fights Crime!, which became A Moon, a Girl…Romance, which became Weird Fantasy, a hint of the horrors to come.

My mother remembers none of this now. She’s living out her twilight days in an assisted-living community where she smokes cigarettes on porch rockers. I visit for monthly episodes of shopping and restaurant adventures. She has a Ph.D. in epidemiology and a CV as thick as a comic book, but that golden age is over too.