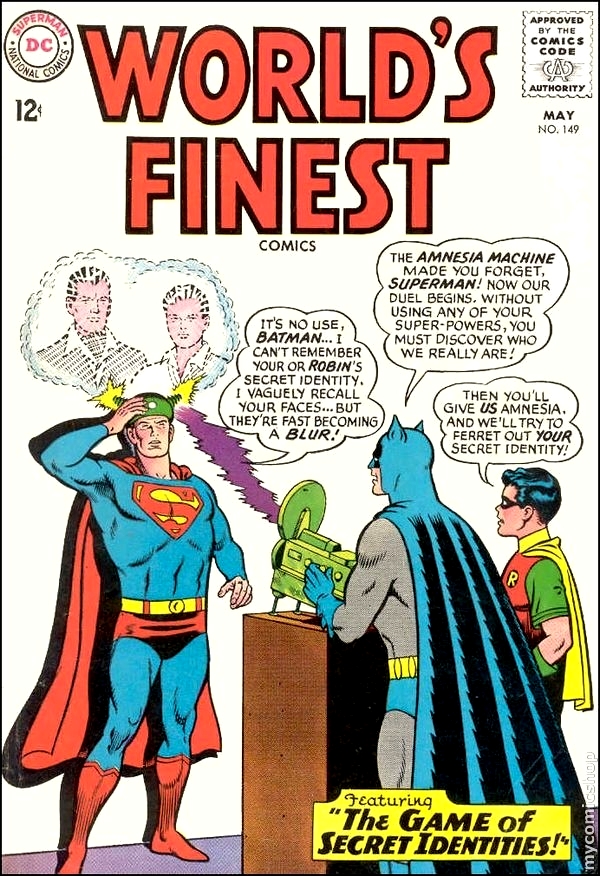

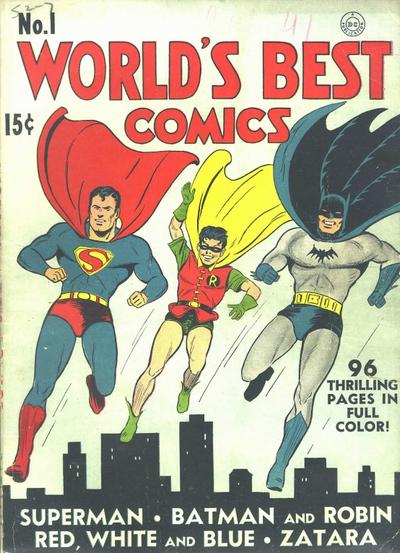

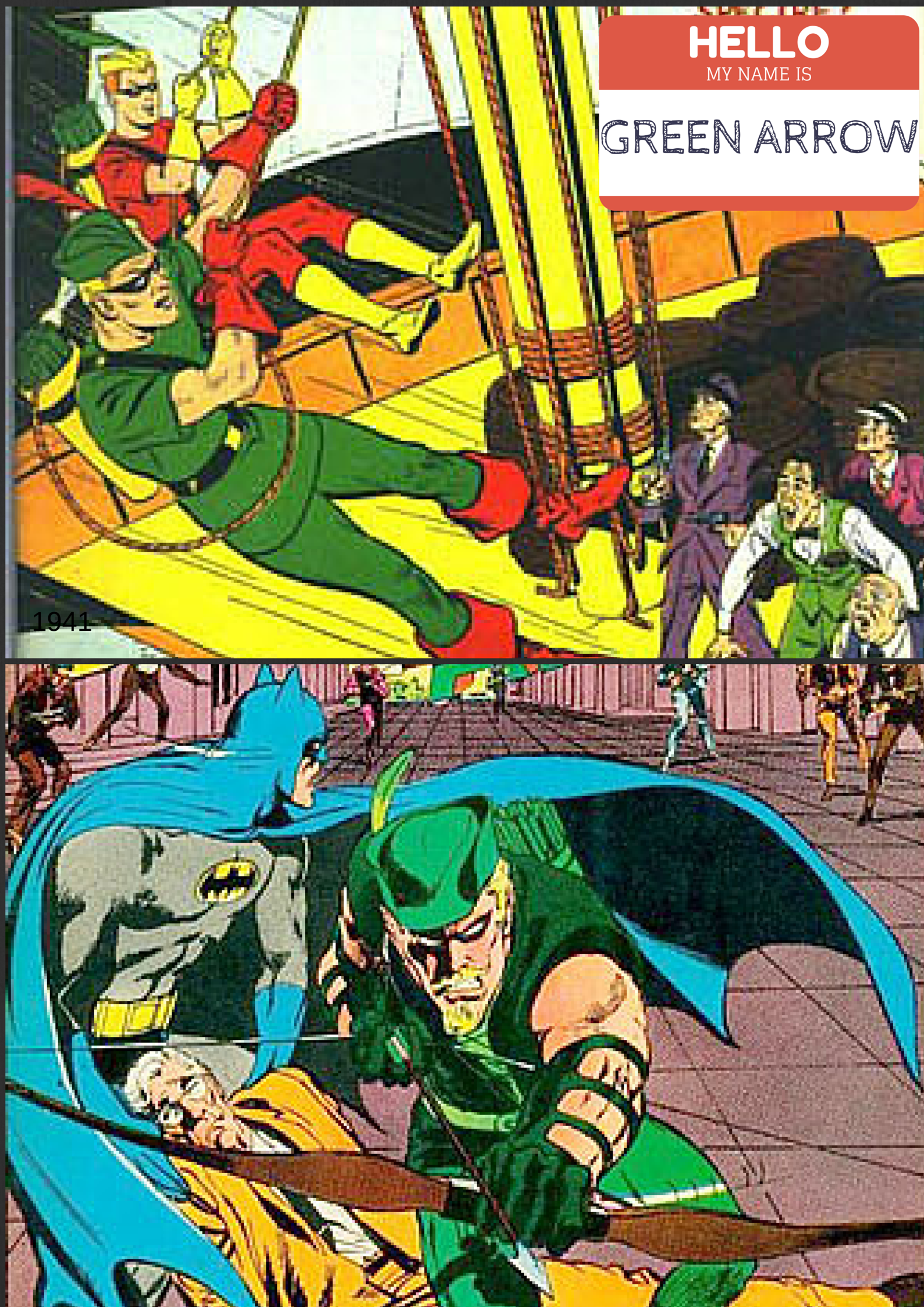

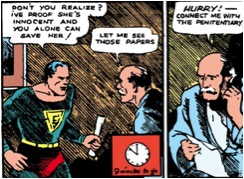

“Superman’s powers weren’t unique,” writes Deborah Friedell, “but his schlumpy double identity was,” because “it is the ordinary person, Clark Kent, who is the disguise.”

The assertion is indirectly Brad Ricca’s, whose biography Superboys Friedell was reviewing, but either way, I have to raise my hand from over here in Bath, England where I’m teaching this month, and say, well, actually, no. Jerry Siegel can only claim uniqueness points if you ignore a range of earlier, disguise-reversing characters, including Zorro and the Scarlet Pimpernel–whose 1934 film incarnation Siegel would have watched before his coincidental stroke of Superman inspiration later the same year.

I’m guessing, however, Jerry didn’t read much by Bath’s most beloved literary daughter, Jane Austen. Which is a shame because she penned the first Clark Kent all the way back in 1817. Austen was more or less on her deathbed at the time, which might explain why she was writing about invalids at a beach resort, and, more sadly, why she never finished.

“Jane Austen left few hints about the direction Sanditon would have taken had her health allowed its completion,” writes Austen expert Mary Jane Curry. “Perhaps future study will suggest why, if Austen family lore is true, Jane Austen called it ‘The Brothers.’” Laurel Ann Nattress thinks the middle of the titular brothers, the very good-looking and lively countenanced Sydney, was “possibly to emerge as the hero.” Maria Grazia agrees (“The male hero seems to be in Jane’s intentions, Sidney Parker”), scolding Juliette Shapiro for her treatment of the character and the subsequent romance (“Rather improbable”) in a completion of Austen’s novel.

Shapiro’s is only one of over a half dozen attempts (including a webseries set in California) to pick up where Austen’s dying hand dropped off. Perhaps so many of them fail because they champion the wrong Mr. Parker. My bets are on Sydney’s kid brother, the mild-mannered Arthur.

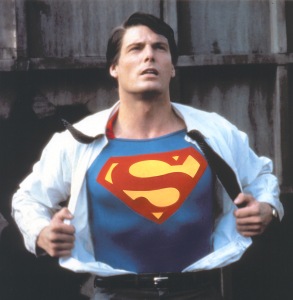

He, like his delicately hypochondriac older sisters, has come to Sanditon to convalesce. Charlotte, Austen’s final protagonist, “had considerable curiosity to see Mr. Arthur Parker; and having fancied him a very puny, delicate-looking young man, materially the smallest of a not very robust family, was astonished to find him quite as tall as his brother and a great deal stouter, broad made and lusty, and with no other look of an invalid than a sodden complexion.” That’s a casting call for Christopher Reeve.

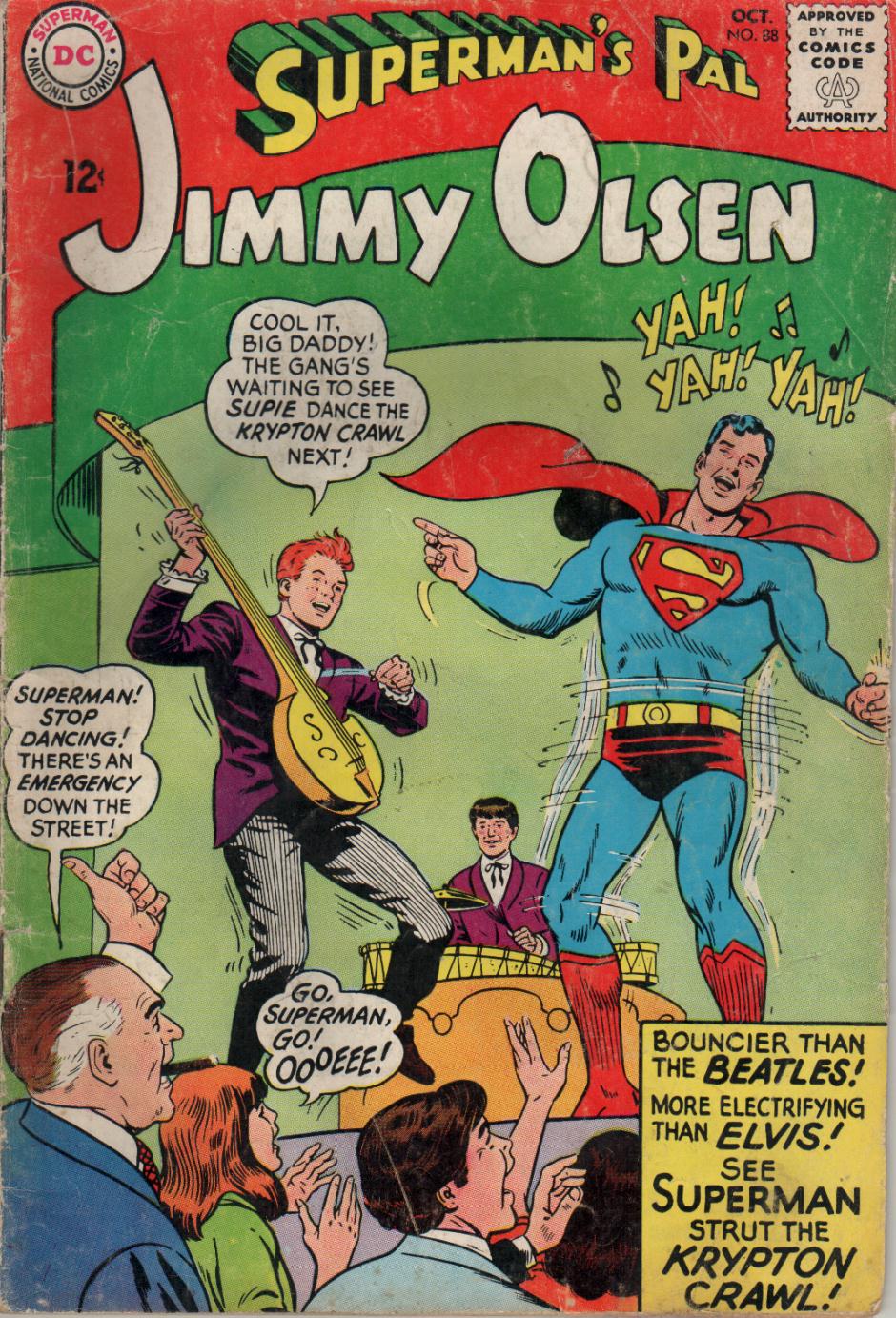

Arthur only receives one scene (more than his feckless brother), but it has all the hallmarks of a Kryptonian slumming as a cowardly weakling. His first line is an apology for hogging the seat by the fire. “We should not have had one at home,” said he, “but the sea air is always damp. I am not afraid of anything so much as damp.” Charlotte is fortunate never to know whether air is damp or dry, as it has always some property that is wholesome and invigorating.

“I like the air too, as well as anybody can,” replies Arthur. “I am very fond of standing at an open window when there is no wind. But, unluckily, a damp air does not like me. It gives me the rheumatism.” He is also, he confesses, “very nervous,” an obscure 19th century condition sadly extinct by the time Siegel was writing, or surely Clark would have suffered it too. “To say the truth, nerves are the worst part of my complaints in my opinion.”

Charlotte recommends exercise. “Oh, I am very fond of exercise myself,” he replies, “and I mean to walk a great deal while I am here, if the weather is temperate. I shall be out every morning before breakfast and take several turns upon the Terrace, and you will often see me at Trafalgar House.” But does Arthur really call a walk to Trafalgar House much exercise? “Not as to mere distance, but the hill is so steep! Walking up that hill, in the middle of the day, would throw me into such a perspiration! You would see me all in a bath by the time I got there! I am very subject to perspiration, and there cannot be a surer sign of nervousness.”

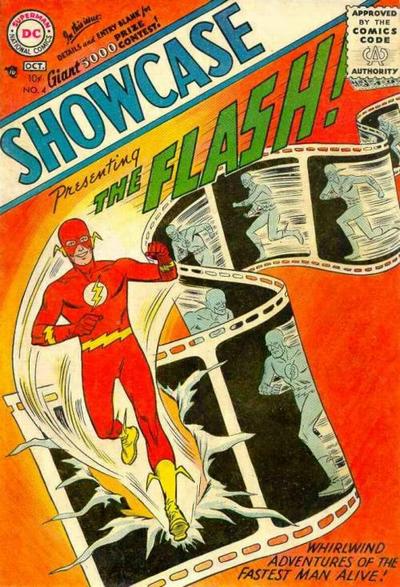

Adding to sweat and humidity, Arthur reveals his most feared form of liquid kryptonite. “What!” said he. “Do you venture upon two dishes of strong green tea in one evening? What nerves you must have! Now, if I were to swallow only one such dish, what do you think its effect would be upon me?” Keep him awake perhaps all night? “Oh, if that were all!” he exclaims. “No. It acts on me like poison and would entirely take away the use of my right side before I had swallowed it five minutes. It sounds almost incredible, but it has happened to me so often that I cannot doubt it. The use of my right side is entirely taken away for several hours!”

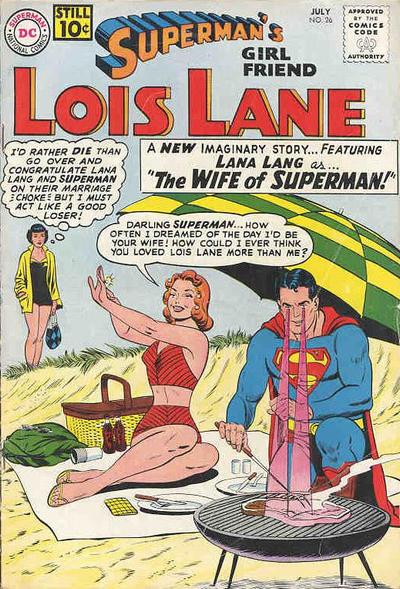

Is Arthur duping Charlotte the way Clark dupes Lois? Hard to say. It is clear, however, that the man is masking deeper appetites. Although he pretends, “A large dish of rather weak cocoa every evening agrees with me better than anything,” Charlottes observes the drink “came forth in a very fine, dark-coloured stream,” prompting his sisters’ outrage. “Arthur’s somewhat conscious reply of ‘Tis rather stronger than it should be tonight,’ convinced her that Arthur was by no means so fond of being starved as they could desire or as he felt proper himself.” Arthur has a similar weakness for liberally buttered toast, “seizing an odd moment for adding a great dab just before it went into his mouth.” Wine also does him surprising good. “The more wine I drink—in moderation—the better I am.”

Charlotte, demonstrating the sleuthing skills of a top notch girl reporter, notes “Mr. Arthur Parker’s enjoyments in invalidism,” suspecting “him of adopting that line of life principally for the indulgence of an indolent temper, and to be determined on having no disorders but such as called for warm rooms and good nourishment.” Laurel Ann Nattress (did I mention she has a blog on Austen?) thinks the twenty-year-old has been “cosseted” (presumably by his doting sisters) “into believing himself to be of delicate health.”

That’s the interpretation Bryan Singer adopted for his 2006 Superman Returns. The Man of Steel’s bastard son, the five-year-old Jason, appears to be an asthmatic runt—until he throws a piano at the thug menacing his mother, Lois. Was little Jason just jerking everyone around? Hard to say. But his old man certainly was. The best scene from Quentin Tarantino Kill Bill is David Carradine’s superhero monologue:

“When Superman wakes up in the morning, he’s Superman. His alter ego is Clark Kent. What Kent wears – the glasses, the business suit – that’s the costume Superman wears to blend in with us. Clark Kent is how Superman views us. And what are the characteristics of Clark Kent? He’s weak… he’s unsure of himself… he’s a coward. Clark Kent is Superman’s critique on the whole human race.”

Austen is critiquing us too, our laziness and self-serving foibles, but being also a devoted lover of the marriage plot, would she have left poor Arthur to stew in his rather weak brew of humanity? I’m not suggesting the young man was hiding a capital “S” under his shirt, but Austen seems to have hidden something under there. Lois eventually pulled the glasses off Clark. I suspect Charlotte would have done the same with her tall, broad, and lusty invalid.