Growing up, I wasn’t allowed to use the word “hate.” I was thus forced to create an alternative phrase and came up with “I dislike [it] to the utmost of my abilities.” So let me say this clearly: I dislike Betty and Veronica to the utmost of my abilities. I feel guilty admitting it; Archie and the gang are just so wholesome, so American, and in recent years I’ve even heard that Archie has developed a decidedly liberal bent, but when I was a child Archie’s main girls Betty and Veronica were the bane of my existence. I think most of us have guilty pleasures—embarrassing pastimes or pursuits that give us a tingly, happy feeling, but reading about the catfights and hijinks of Betty and Veronica was a guilty obsession that brought me no pleasure; instead these “best friends, worst enemies” only made this girl feel much, much worse. This is, of course, a very personal reaction, and I’m looking forward to reading Craig Yoe’s upcoming The Art of Betty and Veronica after abandoning the comic in high school. Perhaps I will be able to gain some distance and a better perspective on the iconic role the pair has played in American culture.

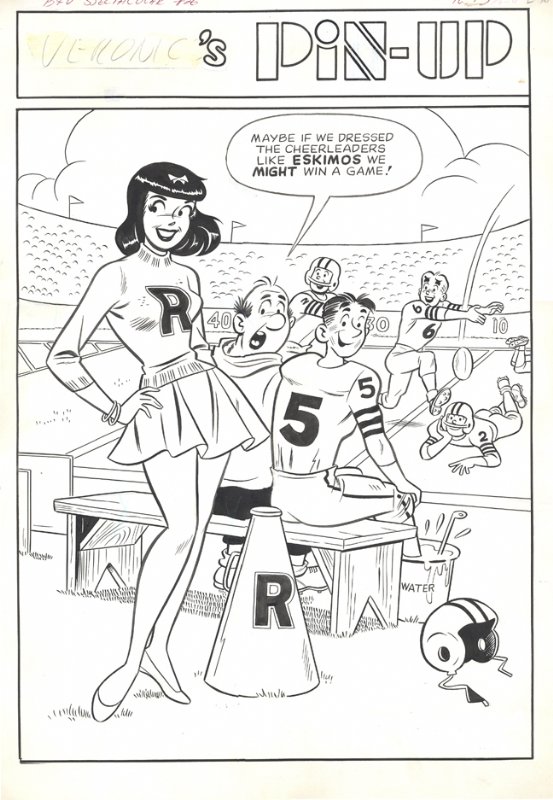

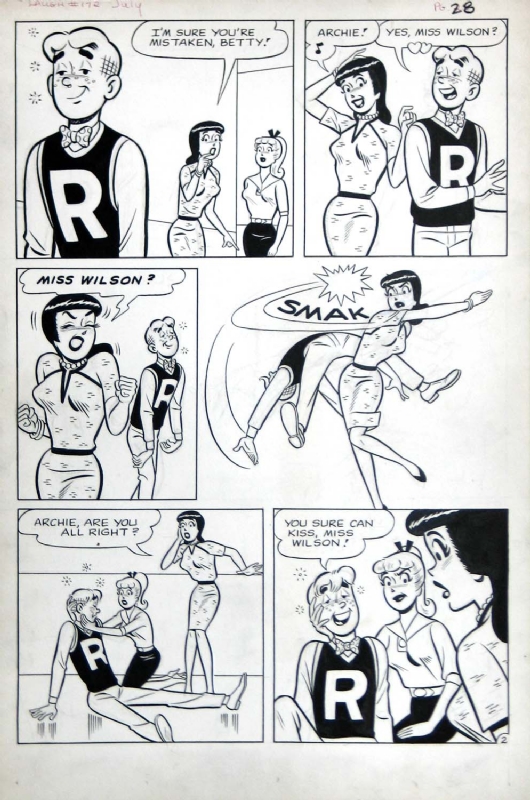

However, when leafing through some old issues of Betty and Veronica from the 1980s, I was immediately overcome with that same strong, repellent feeling from the past as I remembered that, in fact, Betty and Veronica are horrible. In saying this I mean no disrespect to Dan DeCarlo, an artist long associated with updating the look of Betty and Veronica, and well known for his stylized, sexy, and strangely wholesome female characters. Rather, it is the stories, the lives, and the characters of B & V that cause immediate distress. While others might praise the fact that Betty and Veronica remain best friends despite fighting over Archie continuously, I cannot help despising the triangle and the participants in the first place.

Teen magazines frequently asked the question: Are you a Betty or a Veronica? It was a question that I imagine led many girls to despair. I, myself, was certainly no Veronica. Oh yes, she’s gained a cult-like status as a take-charge, empowered female radiating self-confidence and verve, and the comic got a great deal of mileage gently mocking Veronica’s exorbitant wealth and privilege and her lack of real-world knowledge, yet in this playful teasing the stories also served to affirm the great gifts and pleasures of privilege. I had little of Veronica’s sass and grew up in a distinctly middle-class household, examining the riches of the Lodge mansion with a critical eye, all while feeling a sickening jealousy for the girl who had everything, well, except for the feckless Archie. Over and over, Veronica’s slapstick romantic battles with Betty brought out the worst in both, and I couldn’t help but wonder—this is all over Archie? The goofy redhead with the curious, pockmark freckles and crosshatched hair?

If Veronica represented the unattainable dream of confidence, poise, and affluence, Betty acted as I knew I should. As a fellow helpful tomboy who got good grades and tried to please my parents, Betty was more relatable to me. Still (and this likely says something about me), I disliked Betty even more than Veronica: her namby pambiness, her awful subservience, her generic prettiness, and that relentless good cheer. In her upbeat, serviceable wardrobe, Betty was unceasing resourceful, always lending a hand when Archie’s car broke down or Veronica needed help covering for one of her misdeeds. Yuck.

Veronica was downright mean, and Betty, well, she was a doormat. What was there for a little girl to emulate? What kept me dissecting the pages? I believe, if anything, it was Dan DeCarlo’s artistic style that kept me returning to the comic throughout my tween years, despite the queasy feeling the comics gave me. I scrutinized the two female leads intently, studying the perfect hourglass figures, the cutting edge fashions, the upturned noses and wide, perennially surprised eyes as templates for perfection in dark and light. Yet as time went on I slowly gave up the “realistic” teens, gravitating to the superheroes that seemed somehow more real than Betty and Veronica. Spiderman, Batman, Rogue, and Wolverine lived with fear and pain and shame, and yet there was a spark of greatness within them. Somehow, watching these troubled characters make their way, swinging and clawing and punching, felt much more comforting than viewing Betty and Veronica lounge and play on the manicured lawns of Riverdale. Thanks anyway, Archie, but I’ll take the X-Men any day. I guess I really do hate Betty and Veronica.

__________

Click here for the Anniversary Index of Hate.