An edited version of this essay ran in the Chicago Reader a while back.

___________________________

One of the gags in Michael Kupperman’s Tales Designed to Thrizzle Volume 1 is a three panel comic strip featuring “The Head”. As his name suggests, “The Head” is a disembodied…well, head. In the first panel, he announces “Someday I will rule the world!” In the second he admits that “But for now, I have been reduced to flipping burgers with my telekinetic powers! Bah!” And in the third, he sits on a couch watching Three’s Company and muttering “Bah! Such foolish television!”

The lurch from comic-book super-villain cliché to boob-tube homage nicely encapsulates Kupperman’s methods and influences. Alt comics creators may be turning for cred to more respected mediums like literature and memoir, and mainstream creators may be praying for a movie contract, but Kupperman has other telekinetic burgers to fry. On the one hand, he’s steeped in the clunky traditions of comics past — the barmy testimonial pitches (“Men! Is your penis a urine-leaking, chronically unreliable threat to your mental well-being?”), the breathless pulp adventure titles (“I Bothered a Big Fish!), the doofy super-powers (“Under-pants on his head man!”) But on the other hand his overall rhythms — the narratives which turn into advertisements, the skits which end with some whacko randomly barging through a window, the gags which get abruptly dropped and then recur out of context only to be instantly dropped again — all of that seems borrowed, not from his print predecessors, but from the least cred-bestowing of all possible sources. Forget literature and forget film: Kupperman takes his cues from Monty Python and the Cartoon Network: the surreal humor of the small screen.

Television/comics cross-overs aren’t exactly new: the TV show Buffy is currently being continued in comic-book form, as just one example. But Kupperman may be unique in being inspired as much by TV’s form as by its content. In part, this is due to his source material: Monty Python was, in many ways, meta-television. Each show was cobbled together from a mélange of genres — newscasts, sit-coms, dramas, documentaries, cartoons. The humor wasn’t just in each individual section, but in watching the different modes stagger into and over each other. Thus a drawing-room mystery ends with a scoreboard (Constables : 9; Superintendents: 13) and wildly cheering sports crowds, or the BBC end credits are dropped into the show halfway through.

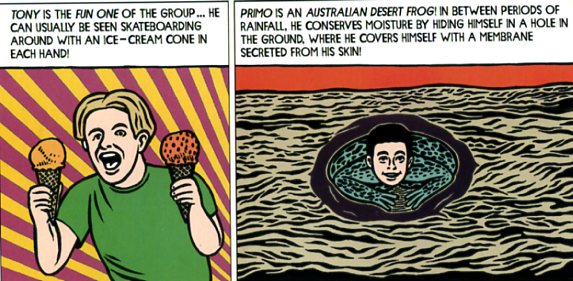

Monty Python, in other words, replicated the heterogeneous feel of television; the sense of switching from show to show and channel to channel; of serialized narratives eternally fractured just because they’d run out of time. This style of humor is fairly familiar now on TV, but it’s still somewhat unusual in comics. In any case, it’s rarely done in any venue with the panache that Kupperman brings to it. In one strip, for example, he segues vertiginously from boy band infomercial to nature special, informing us first that “Tony is the fun one of the group,” moving on to let us know that “Primo is an Australian desert frog!” and concluding that “Alan is too small to be seen by the human eye — but he becomes visible in this close-up view of the human sneeze!”

The boy band skit is an honest-to-God television parody: it works off of documentary genres that are rarely seen in American comics, and the jokes are predicated on abrupt shifts between panels that are formally analogous to camera cuts. But many of Kupperman’s jokes work by adapting the style of surreal juxtaposition to a specifically comic-book context. Instead of using time sequence, for example, Kupperman often arranges abrupt shifts through layout and space. A mostly text choose-your-own space adventure is illustrated with random drawings that have nothing to do with the story. An advertisement for 4-Playo, a robot that provides foreplay, takes up most of a page except for an unobtrusive, dark-colored banner at the bottom that announces: “Let’s All Go to the Bathroom! A message from the Bathroom Council.” As in Chris Ware’s early comics, many of the book’s pages are designed not around a single narrative-driven punch-line, but rather as a carefully arranged clutter of fake ads, strips, text blocks and random gags. The result is a clankily retro tribute to the days of comics past when the medium was, like television, a mass art form, and so had more in common with television’s hucksterism and heterogeneity (these days most comics don’t even have outside ads.)

Not that every one of Kupperman’s lay-outs looks like those old comics. On the contrary, one of most impressive things about Tales Designed to Thrizzle is the creator’s versatility, as artist, writer, and designer. Kupperman’s art is always instantly recognizable; his drawings are deliberately stiff, and his figures pose oddly against his backgrounds, so that everything looks like collaged clip art. Yet from within those self-imposed limits, he manage to create an enormous range of variation. On some pages, he utilizes a heavily detailed black and white cross-hatch style which almost creates moiré patterns; on others, he uses stencils; on others, he places relatively simplified colored figures against plain backgrounds. His designs too are extensively varied, from full-page splash panels to fake text ads with faithfully reproduced fonts, to the beautiful repetitive wallpaper patterns at the end of each issue.

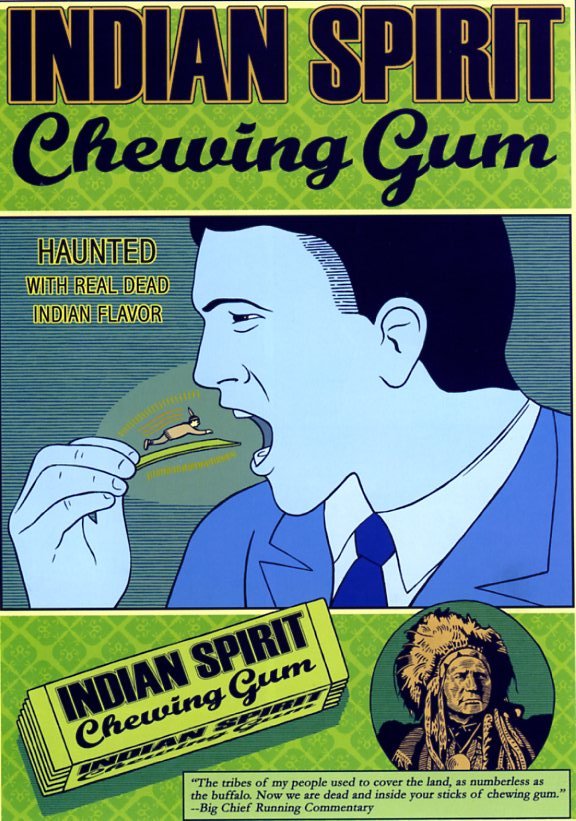

Tales Designed to Thrizzle, in other words, is a monument not only to silliness, but to craft….which is perhaps the way in which it most clearly departs from its television inspirations. Not that there wasn’t a lot of skill and talent involved in creating Monty Python sketches or Adult Swim cartoons. But (with the exception of Terry Guilliam’s segments, of course) television very rarely pays attention to visual aesthetics in the way that Kupperman does here. His ad for Indian Spirit chewing gum, with its patterned background, bizarre conflations of scale (a tiny Indian about to be swallowed by a giant Caucasian) and stark cut-out feel has a constructivist look which flirts perilously with high art.

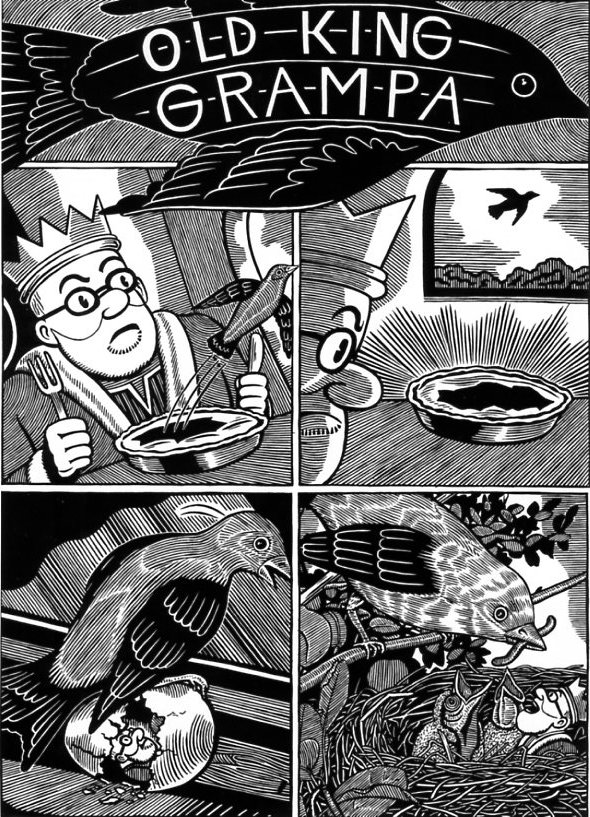

Several of Kupperman’s bizarrely lyrical Cousin Grampa strips do a good deal more than flirt. In one of these, “Old King Grampa”, the titular elderly monarch watches a bird fly out of his pie and then out the window.

The bird then hatches an egg, inside of which waits a tiny king. Finally in the last panel the king and two baby birds sit in a nest, mouths gaping open for a worm from their mother. The way in which deferred oral pleasure leads seamlessly to infantile fantasy is queasily Freudian, and the page is entirely wordless, giving it a serene wrongness that Terry Guilliam’s cartoons, with their aggressive muttering and laugh track, never managed. Further, the drawing is in Kupperman’s detailed, cross-hatched style; you can almost feel the baby birds’ beaky cheeks pressed up against the king’s bearded jowls. In the panel where the mother bird is hatching the egg, Kupperman has her beak parted and motion lines behind her head. She’s giving a little silent squawk and jerk of joy as her bearded devourer/child is born. In that little detail, the cheerful violation of Monty Python bleeds seamlessly into the cheerful violation of something like Un Chien Andalieu or Kafka. Not that Kupperman needs to appeal to film or literature. Why would he, when he can just as well make television into art?