Editor’s Note: This first appeared as a comment on Heidi MacDonald’s recent post “So What Does a Gal Have To Do to Get Into the Comics Journal Anyway?” Annie edited her comment slightly before reprinting it here.

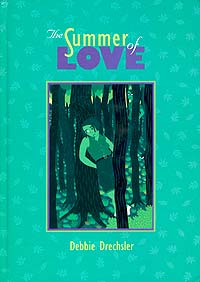

I grew up idealizing male cartoonists: Berkeley Breathed, Herge, Schulz, Jim Davis, Gary Larson, Maurice Sendak, and unbeknownst to me at the time, Art Spiegelman (for his work on the garbage pail kids). I had literally no idea I could even be a cartoonist until I got older–I had unconsciously relegated the vocation to the exclusive world of men. Until I rifled through my first roommate’s collection and had my mind blown open by Phoebe Gloeckner, Debbie Drechsler, Julie Doucet, Lynda Barry, and Love and Rockets (I was still too scared of myself to pick up a copy of Dykes to Watch Out For> and plus I was a punk, so I got my lesbian comics fix with L&R at the time).

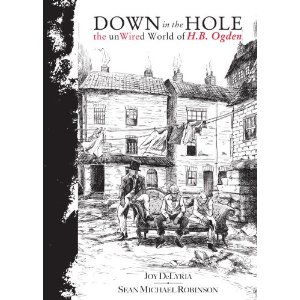

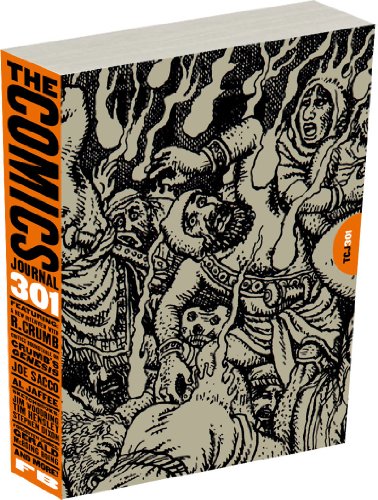

I remember when Dylan (Williams) told me Debbie Drechsler’s Summer of Love was the most important graphic novel in his life, his favorite book. i think he is the only man I have even heard bring her merits up in a conversation. For the comics class we were teaching, he suggested we assign the interview with Drechsler in TCJ # 249. But when I read it I was appalled at Groth’s insensitivity, disrespect and dismissal. Like, it was reaaally bad. And guess who stopped drawing comics altogether (shortly after creating the #1 book in Dylan’s library)?

I remember when Dylan (Williams) told me Debbie Drechsler’s Summer of Love was the most important graphic novel in his life, his favorite book. i think he is the only man I have even heard bring her merits up in a conversation. For the comics class we were teaching, he suggested we assign the interview with Drechsler in TCJ # 249. But when I read it I was appalled at Groth’s insensitivity, disrespect and dismissal. Like, it was reaaally bad. And guess who stopped drawing comics altogether (shortly after creating the #1 book in Dylan’s library)?

I have not been able to stomach Groth’s interview with Gloeckner in the comics journal long enough to finish it (haven’t seen any new comics from her for awhile, though I am anticipating her newest project, a book that takes a close look at the femicides in Juarez. Wonder how that one’s going to go over with critics?)

By the time the interview with Alison Bechdel came out in #287, someone had the sense to ask a woman to interview her–but then added an addendum from some dude at the end who felt that the woman interviewer had not been thorough enough (I thought the interview was brilliant) and proceeded to ask Alison a bunch of asshat questions including something about masturbation to which she replied “did you ask Crumb these questions?” Reading this addendum turned my thrill at reading the article a little sour.

So I’m saying, all this relates to the environment of comics at large, the confidence of women artists, and the inclusion of people besides just straight white men. Groth’s comment about what is ‘good’ or not is the rule, not the exception. I cannot tell you how many women, queers, people of color have told me that they used to draw but stopped completely after someone told them their drawing was not ‘good’, because it did not look like what the straight white men were drawing. I’ve heard this from dozens and dozens and dozens.

My experience teaching in the IPRC comics and certificate program in Portland illustrates this point. Pre-program, we had a meeting to decide how to divide up the accepted applicants between the two teams of teachers (two different classes). When I entered the room, I saw that the director had already divided the applications up into two groups: ‘good art’, students whose work was perceived as ‘more advanced’ were on one side of the table (assigned to the teacher he considered the ‘expert’–a man) while on the other side were the beginners, the ‘unclassifiable’ applications, and the artists that he considered ‘less advanced’–assigning them to the ‘fun’ team of teachers (one of which was a woman). As I circled the table and read the applications, a rock grew in my stomach. “Did you notice that nearly all the artists you consider ‘good’ and ‘advanced’ are men, and the artists you consider ‘less good’ and ‘less advanced’ are all women?” Radio silence. I was the only female in the room. It took several minutes before the other men reading the applications could assess the situation and reiterate my observation to the director who eventually acknowledged (albeit through a different, male teacher) that my critique was valid. The gender imbalance being obvious, at first glance, only to me.

Is it any wonder that The Comics Journal gets so many proposals from women on the subject of comics education? It’s one of the only spheres in which we are granted authority, at best. Of course women want to have a say in what gets taught and how in all of the new schools.

The irony of a company whose name and image were built on the foundations of feminist artwork/stories, drawn by two people of color, whose most loved and reknowned characters are two Latina queers and a badass lady who carries a hammer around for protection and rage, is not lost on me.